Russia-Ukraine war: The battle for Odesa

The fight for the Black Sea port could influence the outcome of the war and affect regional security, experts say.

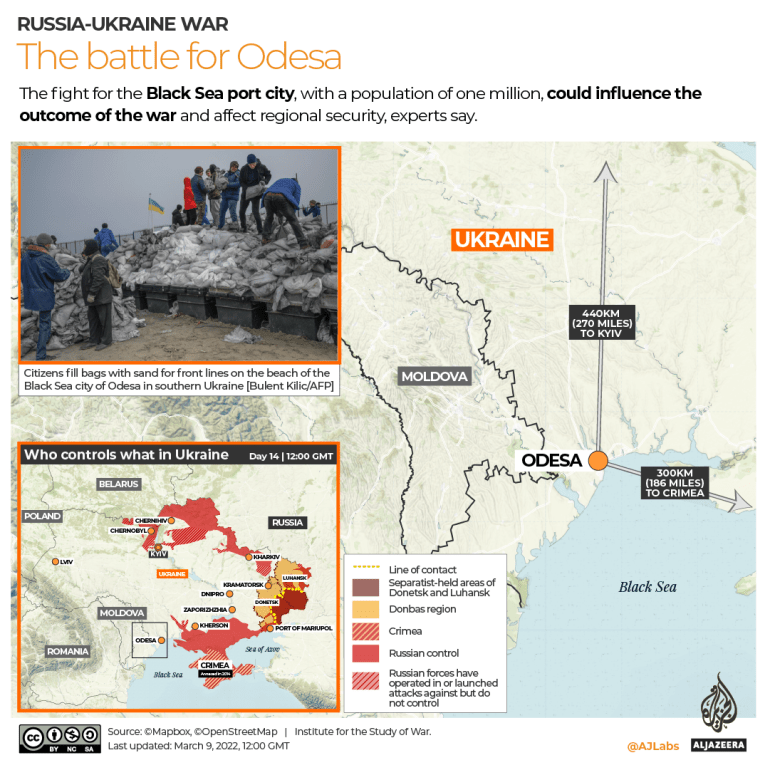

Two weeks into Russia’s war in Ukraine, Kyiv’s forces are preparing for a potential attack by Moscow’s troops on the historic port city of Odesa on the Black Sea.

Situated 300km (186 miles) west of the Russian-annexed Crimean peninsula, the city is seen as a strategic asset by both Ukraine and Russia – and its fall would have significant repercussions, not only for the two countries, but also for the wider Black Sea region, experts warn.

Keep reading

list of 4 itemsRussia-Ukraine war: List of key events, day 791

Ukraine wins bipartisan US support, strikes Russia from afar

In Ukraine, low hopes for the liberation of lands occupied by Russia

Russian troops, advancing west of Crimea, have already taken the port city of Kherson and arrived at Mykolaiv, just 120km (75 miles) east of Odesa. Russian navy ships have been spotted close to Ukrainian territorial waters, raising fears of a possible attack from the sea.

On Sunday, Ukrainian President Volodymyr Zelenskyy said the Russian army is planning a violent assault on the city, calling it an “historical crime”. Earlier last week, he dismissed the civilian governor of Odesa province, Serhiy Hrynevetsky, and replaced him with Maksym Marchenko, an army colonel and former leader of the controversial Aidar battalion, which has fought in the Donbas region in Ukraine’s east since 2014.

The Ukrainian military has already established defensive positions across Odesa, imposed a curfew and set up roadblocks at all entrances to the city of one million people. The ports have been closed to commercial shipping, while the evacuation of civilians has begun.

‘A pivotal lifeline to overseas’

Odesa is of strategic military and economic importance to Ukraine. After losing its naval base in Sevastopol following the annexation of Crimea in 2014, the Ukrainian navy moved its headquarters there.

Its three ports also play an important role in the economy of the country. Some 70 percent of all Ukrainian imports and exports are in the form of sea cargo – and Odesa handles about 65 percent of that.

“[For Ukraine,] Odesa represents a pivotal lifeline to overseas,” Alexey Muraviev, associate professor of national security and strategic studies at Curtin University, told Al Jazeera. “If Russia seizes Odesa, it will effectively cut off Ukraine from overseas trade and military aid.”

The loss of the port city could have significant ramifications for Ukraine and its war effort and give Russia a strategic advantage. Ukraine does not have any other large ports to rely on in case it loses control of its third largest city, allowing Russia to effectively dominate the whole of the northern Black Sea coast.

“In the context of the Russia-Ukraine war, the battle for Odesa would play one of the key roles in determining the future political outcome of the current conflict,” Muraviev said. “For Russia, the complete control of the Ukraine’s Black Sea and the Sea of Azov coasts may [be more important] than the seizure of Kharkiv or western Ukraine combined.”

‘They want Odesa intact’

Capturing Odesa would also have a particular symbolic significance, given the important status it holds in Russian culture and history.

Founded in 1794 by Russian Empress Catherine the Great, Odesa became a crucial seaport and a cosmopolitan urban centre, home not only to Russians and Ukrainians, but also to Armenian, Bulgarian, Greek, Jewish and other communities. With its ornate architecture designed by Italian artists and rich cultural life, the city turned into one of the symbols of Russian imperial prestige and power.

The local authorities have expressed hope that the port city’s historical importance could spare it from the destructive aerial assaults other Ukrainian cities have experienced.

“They want Odesa intact, Odesa’s infrastructure, architecture and strategic meaning. They want all of those undamaged. That’s why I think Odesa will be subject to a special operation,” Mayor Gennadiy Trukhanov told the US’s Public Broadcasting Service.

The city is also home to a sizeable ethnic Russian community, a factor that some Russian observers have claimed could help a military attempt to capture the city.

In 2014, as separatist forces backed by Russia started armed rebellions in the eastern Donetsk and Luhansk regions against the central government in Kyiv, Odesa also witnessed some violence. Ukrainian ultranationalists clashed with pro-Russia groups opposing pro-Western protests, which culminated in the deaths of more than 40 people.

In his February 21 speech recognising “the independence and sovereignty of the Donetsk People’s Republic (DPR) and the Luhansk People’s Republic (LPR)”, Russian President Vladimir Putin pledged to find those responsible for the violence in Odesa and hold them accountable.

But according to Anton Barbashin, a political analyst and editorial director of Riddle Russia, the events eight years ago and the presence of ethnic Russians in the city are unlikely to help Russia advance in Odesa.

“In 2014, the Ukrainians stopped an attempt to make Odesa into Odessa People’s Republic. There is clearly not a lot of pro-Russia sentiment, especially at this moment,” he told Al Jazeera.

In his view, the current difficulties the Russian army is experiencing in advancing on a few fronts could also reflect on its ability to capture Odesa. The Russian forces have been overstretched and ensuring supply routes and reinforcements could be a challenge.

“We do see how tough it is for Russian forces to attempt to occupy territories that are much closer to Russia than Odesa,” Barbashin said.

Transnistria and regional security

The capture of Odesa could have negative consequences not only for Ukraine, but also for the security of its neighbours. Defence analysts have pointed out that controlling the city would enable the Russian forces to open a land corridor to the breakaway region of Transnistria, which has sought independence from Moldova since the 1990s.

The region hosts some 1,500 Russian troops deployed as part of a peacekeeping force created following a 1992 ceasefire agreement between Chisinau and Transnistrian separatists. So far, Russia has not recognised the self-proclaimed Pridnestrovian Moldavian Republic, but there has been speculation that Moscow may seek to include it in a “union state” along with Belarus, the DPR and LPR, Abkhazia and South Ossetia.

“The idea of getting all these ‘lost’ Soviet territories back to Russia … was endorsed by a number of foreign policy circles,” said Barbashin.

A move towards Transnistria would likely destabilise Moldova, which like Ukraine, is not a NATO or a European Union member. On March 3, the Moldovan government filed a formal request for accession to the EU, fearing a spillover of the Russian-Ukrainian war.

Further south, Bulgaria and Romania have also watched anxiously the events in Ukraine.

According to Dimitar Bechev, a visiting scholar at Carnegie Europe, the two countries have already felt threatened following the annexation of Crimea and Moscow’s deployment of missile systems and expansion of its Black Sea fleet on the peninsula.

“[The potential fall of] Odesa would only strengthen Moscow’s [hand],” he told Al Jazeera. “In practical terms, this would remove the territorial buffer between us [Bulgaria and Romania] and Russia.”

In his view, this is likely to result in NATO beefing up its ground presence in Bulgaria and Romania. A heightened navy presence is unlikely given the limitations set in the Montreux Convention of 1936, which governs the use of the Bosporus and Dardanelles straits. The document, which both Romania and Bulgaria are signatories to, restricts the passage of navy ships that do not belong to the Black Sea.

You can follow Mariya Petkova on Twitter @mkpetkova