As California turns to renewables, who will clean up old plants?

Some fossil-fuel facilities have been abandoned by their owners, with cities saying they cannot afford the costs to tear them down.

Oxnard, California, US – For years, poor communities of colour have lived with a disproportionate share of the burdens generated by fossil-fuel production, including pollution and proximity to industrial sites.

Today, as California seeks to transition to renewable energy for 100 percent of its electricity needs by 2045, the future of some of the US state’s 217 natural gas plants is uncertain. In a cruel twist, the same communities that have suffered from generations of pollution could now be saddled with the costs of dismantling and cleaning up old fossil-fuel facilities.

Keep reading

list of 4 itemsJapan’s greenhouse gas emissions fall to lowest on record

Mexico’s president slams opposition for voting down power bill

How are US special interests undermining climate action?

Oxnard, situated around 100km northwest of Los Angeles on California’s central coast, is one such city. Home to a largely working-class Latino community, it has seen numerous industrial facilities litter its otherwise pristine coastline. Some now lie empty, as questions linger over the future of this land and the substantial clean-up costs.

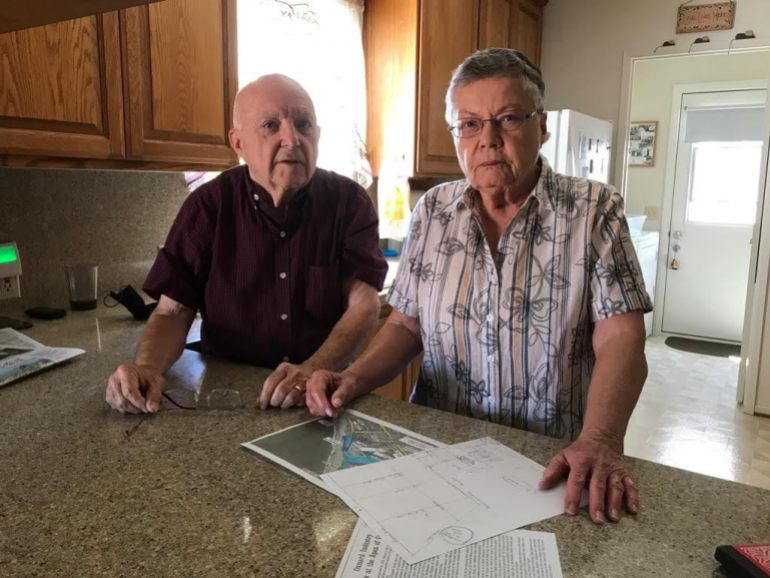

For Shirley and Larry Godwin, who bought a home in Oxnard in 1966, such questions have turned them into “accidental activists”.

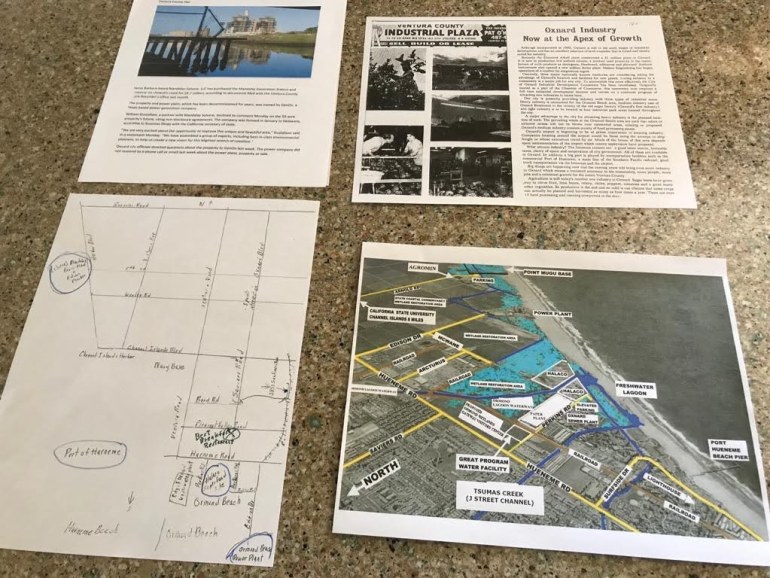

On their kitchen table, they place a hand-drawn map of the area surrounding their neighbourhood, including a slag heap abandoned years ago by the company that operated it, and two natural gas plants – one dormant and one active, both fuelling contentious debate within the community.

Several blocks away is a plant that produces paper for cardboard boxes, and a small train track shuttles goods past the Godwins’ backyard several times a day.

“Whenever we would take our children to the beach, you could count on seeing the exhausts coming out from one of the gas plants,” Shirley Godwin told Al Jazeera. “Our community doesn’t agree on everything, but there’s one thing that unites almost everyone, and that’s that almost nobody wants them [energy companies] to stay.”

Environmental justice

In 2018, after years of mobilising by local groups such as Central Coast Alliance United for a Sustainable Economy (CAUSE) around issues of environmental justice and renewable alternatives, Oxnard rejected an attempt by an energy company, NRG, to build yet another natural gas plant on its coast.

“It’s a part of California’s coast people don’t see, coastal communities like Oxnard with large working-class communities of colour,” Lucas Zucker, CAUSE’s policy and communications director, told Al Jazeera. “It’s not a coincidence that these stretches of industrialised coastline are in communities like Oxnard. As the state transitions to renewables, what happens to this fossil-fuel infrastructure?”

A recent study conducted by the University of California, Berkeley in coordination with various community organisations, including CAUSE, found that Oxnard and the surrounding area are at heightened risk of industrial sites flooding due to sea-level rise driven by climate change.

The same study found that disadvantaged communities are more than five times as likely to live within one kilometre of industrial sites at risk of flooding by 2050. “Sea level rise, toxic facilities and social vulnerability all map onto each other,” Zucker said.

For those charged with threading the needle between a future without fossil fuels and the thorny dilemmas of how to finance the clean-up of old industrial sites, there is no easy path forward.

In 2020, Oxnard City Manager Alexander Nguyen helped to broker a deal with the energy company GenOn, extending the lifetime of the Ormond Beach Generating Station, a natural gas plant, until 2023, in exchange for a portion of profits – $25m – going into a trust dedicated to clean-up.

“People ask what we’ll do if $25m isn’t enough to dismantle the site, and I always give the same answer: We’ll still be $25m ahead of where we would be otherwise,” Nguyen told Al Jazeera.

The California State Water Resources Control Board had initially suggested that Ormond, along with a number of similar plants throughout the state that use ocean water for their cooling systems in a way that damages the ecosystem, be shut down. But in September 2020, responding to concerns that without the plants, the state’s energy supply might be inadequate, the board suggested (PDF) that they remain open until 2023.

Unwanted ‘monuments’

Nguyen points to what he calls “monuments to the 20th century” scattered throughout California: gas plants that have been unceremoniously abandoned by the companies that once operated them, leaving cities, such as Morro Bay, unable to afford the prohibitive costs of tearing them down.

“In California, a plant can be forced to close, but not dismantled. So other plants have been decommissioned, and now they’re just sitting there, rusting and leaching into the ground,” Nguyen said. “What I didn’t want is for that to occur in Oxnard.”

GenOn did not respond to a request for comment from Al Jazeera regarding the deal with Oxnard to extend the lifetime of the Ormond plant.

A short drive north, Oxnard’s coast is bookended by another natural gas plant, the Mandalay Generating Station, which has been dormant since 2018. A local newspaper, the Ventura County Star, reported that the site was recently sold to an LLC, formed earlier this year, for around $8.7m. According to the paper, the new owners have offered no information on the future of the site, and elected officials have expressed hopes that it will be something besides industry.

Mandalay was previously owned by GenOn, the same company that oversees the Ormond plant. Visible from kilometres away, the shuttered plant and its massive smokestacks dominate the landscape.

Even with the future of such sites in question, the Godwins remain upbeat about what lies ahead for their community, as they speak with fierce pride about the city they call home.

“We always say we were two of the least likely people you could find to get involved in activism. I’m terrified of public speaking,” Shirley Godwin said. “But we love our community. When we got involved with these issues, we met so many people from all different cultural and class backgrounds. It’s a diverse community, and that’s what we like about it.”