Putin’s Russia: From a ‘great power’ to a ‘pariah state’

Will the invasion of Ukraine prove to be the Russian president’s undoing?

On March 29, more than a month into the war in Ukraine, the Russian Ministry of Defence announced it was scaling down its military operations in the northern part of its neighbouring country.

The failure of the Russian army to achieve a quick victory has given rise to speculations about tensions within the Kremlin and President Vladimir Putin’s displeasure with his staff.

Keep reading

list of 4 itemsPoland arrests man over suspected plan to kill Zelenskyy

Germany arrests two dual nationals over alleged Russian sabotage plot

Russia pounds Ukraine’s cities and front lines as air defences dwindle

Some observers have claimed the decision to invade Ukraine on February 24 reflected Putin’s personal concerns rather than geopolitical necessity, and that as he turns 70 this year, he is increasingly preoccupied with his historical legacy. Amid military losses in Ukraine and a deepening economic crisis as a result of far-reaching Western sanctions imposed over the invasion, his achievements may be undermined, experts warn.

So what has Putin accomplished in his 22 years in power and what is at stake for him in this war?

‘Law and order’

In the late 1990s, Putin, a former KGB agent and bureaucrat in the presidential administration of Boris Yeltsin, emerged as one of his possible successors. Yeltsin was deeply unpopular and perceived as a weak leader, after overseeing a bumpy transition from communism to market economy and electoral politics.

The search for his successor focused on someone who could project a different image – of strength and ambition.

“Russians were craving strong leadership … Law and order were the key words,” said Russian political commentator Abbas Gallyamov. “The general mood in the country was patriotic, anti-NATO.”

According to him, Putin played on these sentiments and presented himself as someone who could put Russian domestic affairs in order and stand up to perceived humiliation by the West.

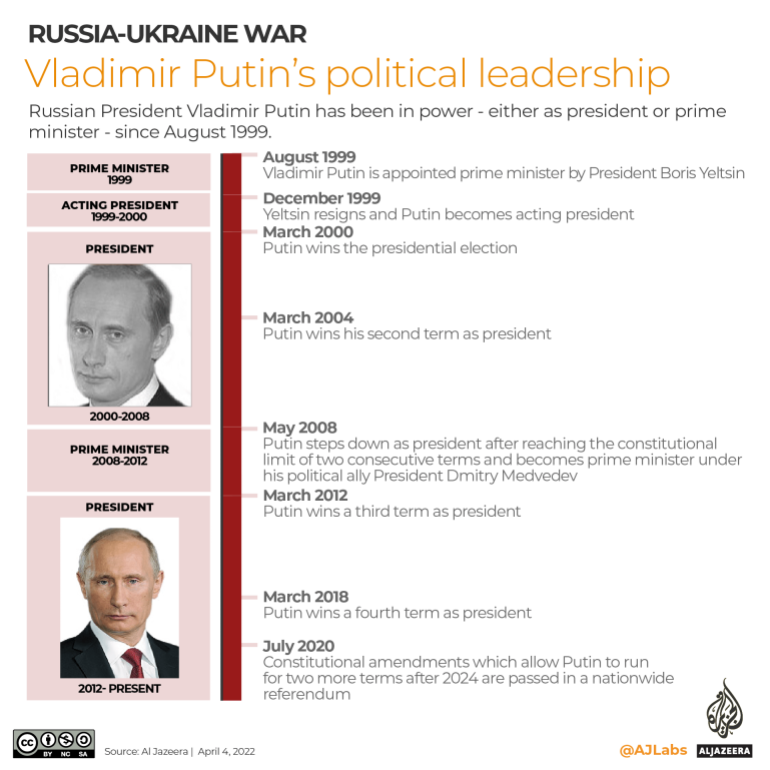

After a rapid turnover of prime ministers, including two – Yevgeny Primakov and Sergei Stepashin – who also had an intelligence background, Putin was appointed to the same post in August 1999, which paved the way for his presidency. In March 2000, he won the presidential election with 53 percent of the vote.

The society’s desire for a more assertive leader allowed the new president to undertake political reforms that strengthened the state, reversed decentralisation and even infringed on democratic institutions and press freedom.

“The more authoritarian he was becoming, the more Russian people liked it,” Gallyamov said.

In parallel, Putin also strengthened the security and intelligence agencies and sought a decisive victory in the second Chechen war. He also responded with heavy-handed security operations following attacks in Moscow in 2002 and Beslan in 2004, embracing the United States’ so-called “war on terror” narrative.

Despite facing some criticism for his democratic record and adopting some anti-Western rhetoric, the Russian president enjoyed Western support. At the 2005 Victory Day celebration in Moscow, surrounded by state leaders from China, France, Germany, Japan and the US, Putin declared: “It is our duty to defend a world order based on security and justice and on a new culture of relations among nations that will not allow a repeat of any war, neither ‘cold’ nor ‘hot’.”

But the expansion of NATO eastwards caused some tensions, expressed by Putin in his famous speech at the Munich Security Conference in 2007 in which he accused the US of “having overstepped its national borders in every way”. Analysts have pointed to the 2008 war in Georgia, in which Russian troops fought alongside forces of two breakaway regions against the Georgian army, as a demonstration of the Kremlin’s red lines after Tbilisi tried to pursue NATO membership. Even after the conflict, however, positive engagement with the West continued and in 2009, the administration of US President Barack Obama announced a “reset” in relations with Russia.

In his first two terms as president (2000-2008), Putin also presided over spectacular economic growth and development in Russia, boosted by high oil prices and macroeconomic reforms carried out in the 1990s. The economy grew by between 5 and 10 percent annually. Liberal economists on his team worked on boosting foreign direct investment and the domestic business climate.

Standards of living improved for the average Russian, while the urban middle class consolidated. Between 2000 and 2010, the average wage increased almost tenfold.

“Putin was a very lucky politician because he came to power in 2000 when the [Russian] economy had passed the most difficult times,” said Sergei Aleksashenko, who was Russian deputy finance minister in the 1990s. “If Putin had retired and left the office in 2008, he would have been accepted as a great president of Russia”.

Solidifying control

But he did not. Barred to run for a third consecutive term, Putin handed over the presidency to Dmitry Medvedev in 2008 and returned to the post of prime minister.

According to Gallyamov, who joined Putin’s administration at the time, the incumbent president did consider retirement seriously. In the first few months of the premiership, he seemed very relaxed and did not take on a lot of responsibilities, perhaps planning to allow Medvedev to go for a second term.

“He tried to let the reins loose but then something happened,” Gallyamov said. The change in Putin’s attitude roughly coincided with the onset of the 2008 global financial crisis which made him get more involved in the country’s affairs, he explained.

Then, in 2011, the Arab uprisings and specifically, the NATO campaign against Muammar Gaddafi’s government in Libya, increased his feeling of insecurity.

“He felt that he cannot be safe, especially given that the Russian opposition was very vociferous about this case. They were all saying, ‘Putin you will end up like Gaddafi’,” Gallyamov said.

In December of that year, a few months after Putin announced his presidential bid, anti-government protests erupted in Moscow, which he blamed on then-US Secretary of State Hillary Clinton.

After securing a third presidential term, this time for six years, Putin’s anti-Western rhetoric intensified and so did his criticism of “colour revolutions” – popular protest movements in the post-Soviet space seeking change of government. This culminated in Moscow’s forceful response to the 2013-14 Maidan protests in Ukraine, in which Russian troops were sent to the Ukrainian region of Crimea to occupy it and a separatist rebellion was instigated in the Donbas region.

A more assertive foreign policy was also reflected in Russia’s military intervention in Syria in 2015 and the deployment of Russian mercenaries in Libya in 2019, as well as stronger engagement with several Middle Eastern and African states.

At home, meanwhile, Putin imposed a number of measures seeking to curb the political space for dissent. In 2012, the Russian Duma passed the so-called “foreign agent law”, which sought to curb the activity of civil society organisations receiving foreign funding; in 2019, it was expanded to include individuals and media organisations. In 2014, the lower house of parliament also approved legislation making any protest without prior approval from local authorities illegal.

In 2019, the Kremlin also began clamping down on the organisation of opposition leader Alexey Navalny after a series of revelations about government corruption by his team. Navalny survived an assassination attempt with a chemical agent in 2020, which he accused Russian intelligence agents of carrying out, and was subsequently jailed.

Putin’s drive to solidify his grip on power extended into the Russian economy, which suffered a downturn after global oil prices collapsed in 2014-15 and Western countries imposed sanctions due to the Russian intervention in Ukraine.

According to Aleksashenko, in the 2010s the Russian president sought to increase his control over the energy and banking sectors, as well as big Russian businesses.

“Putin recognised that if he did not control private business, [its] financial flows, if he did not limit connections between private business and the political opposition, he would have faced significant challenges,” Aleksashenko said.

Despite the downturn and the increased control, however, Putin’s economic team managed to maintain macroeconomic stability and low inflation, which ensured the living standards of the Russian population did not deteriorate.

Putin’s legacy: ‘A pariah state’

The Russian invasion of Ukraine initially provoked anti-war protests in cities across Russia, but the security apparatus was able to quickly stifle them. The state also clamped down on independent and critical media outlets, cutting off access to alternative sources of information.

A month into the war, both state and independent pollsters have indicated that Putin’s approval rating has jumped some 20 percentage points to 81–83 percent. Independent polling centre Levada also reported support of 81 percent respondents for the war in Ukraine.

While sociologists have warned that legislation effectively criminalising expressions of anti-war sentiment can distort such poll results, Putin enjoyed a similar high rating after Russia’s intervention in Ukraine in 2014. However, it lasted for four years and slumped after his 2018 re-election for a six-year term. The current high rating may also reflect a temporary effect of rallying around the flag in a time of war.

According to Gallyamov, the general trend in Russian society, which started before the invasion, is to move away from venerating strong leaders.

“[People wonder], OK, Putin is strong but why do we still have problems? It is because he doesn’t care about people, he cares only about himself and his entourage and he’s playing his big political games which he likes,” he said. “The people are looking for a leader with a human face, not so authoritarian, not so aloof, not a person who doesn’t care.”

In his opinion, the war will not prevent the domestic legacy he wanted to leave behind – nationalism, conservative values and an image of a strong Russia – from being discredited in the public eye.

Putin’s economic achievements also appear threatened. According to the European Bank for Reconstruction and Development, the Russian economy may contract by as much as 10 percent this year; other estimates put this number as high as 15 percent.

“The war against Ukraine is resulting in decoupling of the Russian economy from the global economy. We don’t know when and how this process will stop,” Aleksashenko said. He predicted that if Putin were to remain in power for another five years, even if he managed to strike some kind of a peace deal, the Russian economy would look like a “mixture of the Soviet economy of 1985 and the North Korean economy of today”.

“The economic legacy of Putin will be … a disaster,” he concluded.

The war in Ukraine is also likely to affect Russia’s standing in world politics, as the country’s leadership faces war crime charges. Following referrals from 41 countries, the International Criminal Court (ICC) announced it has opened an investigation into the Russian invasion of Ukraine. Calls for international inquiries have intensified in recent days after the Ukrainian authorities alleged war crimes were committed in suburbs around Kyiv captured by the Russian army.

According to Mark Galeotti, director of the consultancy Mayak Intelligence, Russia will also have to scale back its geopolitical reach.

“Russia is not going to collapse … but in terms of the impact on the Russian state as a powerful state able to sustain foreign military and political adventures, that’s a very different matter,” Galeotti said. “In terms of Russia’s place in the world, it will be hard for the Russians – and certainly while Putin is in power – to not be considered essentially a pariah state.”

In his view, Putin’s bid to go down in Russian history as a key state builder has failed.

“His legacy will be as someone who from arrogance and hubris […] has basically wasted years of rebuilding Russia’s military, political, economic and soft power capabilities in the world,” Galeotti said.

You can follow Mariya Petkova on Twitter @mkpetkova