Elections in Lebanon, does political change stand a chance?

Al Jazeera discusses with analysts what lies ahead as power has shifted in Lebanon’s sectarian power-sharing system.

Beirut, Lebanon – As Lebanon’s election frenzy cools down, the country has awoken to a new chapter in its dizzying political history.

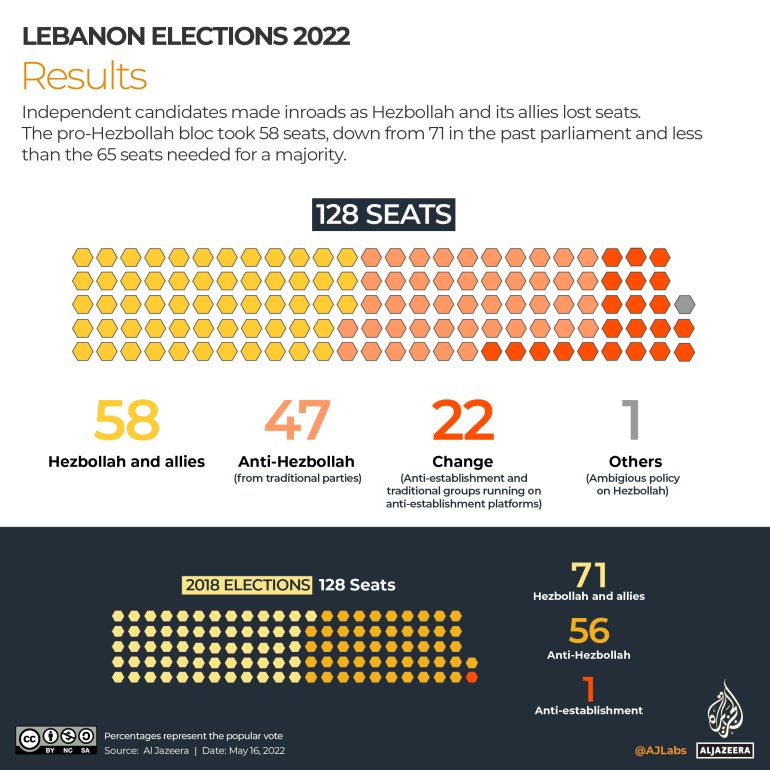

After Sunday’s election result, shifts in the balance of power in the country’s 128-seat parliament and its fragile sectarian power-sharing system have occurred.

Keep reading

list of 4 itemsHezbollah allies projected to suffer losses in Lebanon elections

Lebanon’s pro-Hezbollah bloc loses parliamentary majority

Lebanon election monitors complain of violations, attacks

Lawmakers who for many decades were constant variables in Lebanon’s political equation were unseated. Unfamiliar faces, inspired by the country’s 2019 uprising, were elected and might now breathe new life into an often comatose political system.

But some of the election euphoria is already overshadowed by problems that continue to plague Lebanon for a third year, particularly the economy.

The Lebanese pound, with its value already decimated and down by 90 percent compared to the United States dollar, has plummeted further. Foreign reserves in the Banque du Liban or central bank are diminishing, and petrol and food prices continue to soar amidst fears of both fuel and wheat shortages.

Experts told Al Jazeera that while Lebanon’s election result marks a critical moment in the country’s troubled history, what lies ahead could determine whether Lebanon stands a chance at viability.

Allies let down Hezbollah

The powerful Iran-backed Shia party Hezbollah did not lose any of its seats, but the political allies that helped it maintain a parliamentary majority suffered major blows, both from traditional rival political parties and a new anti-establishment opposition.

Notably, a Greek Orthodox seat and a Druze seat in key areas of influence in southern Lebanon went to anti-establishment opposition candidates: a medical doctor Elias Jradeh and lawyer Firas Hamdan.

Hezbollah’s key Christian political ally, the Free Patriotic Movement, is no longer the biggest Christian party.

However, neither Hezbollah nor the Free Patriotic Movement have conceded defeat, and both have declared the elections a victory.

While political alliances in Lebanon can be fluid, experts say the vote was a huge blow to the once-dominant Christian party.

“I think the Aounists [Free Patriotic Movement] will have to admit that they have objectively lost – even if they’re trying to put a spin on it,” Arab Reform Initiative Executive Director Nadim Houry told Al Jazeera.

Hezbollah’s broad alliances were “weak and fragile”, and elections were one way of demonstrating loyalty, Carnegie Middle East Research Fellow Mohanad Hage Ali explained.

The election results might also indicate shifts in public opinion among Shia voters too, the researcher said, explaining that “alternative Shia votes” might have opted for candidates outside the Hezbollah political alliance.

“[Hezbollah] wanted no vote outside its own political choosing, and they did everything they can to intimidate voters, candidates, and their representatives in their constituencies,” Hage Ali told Al Jazeera, citing numerous statements from Lebanese elections observers about the Shia party.

Political paralysis?

As the economy continues to spiral, the new parliament does not have much time to convene and start the process of appointing a new prime minister and forming a new government. But with no parliamentary majority that traditional factions can use to assume power together, experts believe a political deadlock is possible.

“That’s one scenario with potentially those in the middle [opposition] trying to mediate but not enough to impose an agenda,” the Arab Reform Initiative’s Houry told Al Jazeera.

Lebanon’s prime minister is a Sunni, and the government is divided along the country’s multitude of religious sects and different political forces in parliament. This fragile power-sharing system can quickly lead to paralysis.

“Lebanon is a very difficult country to govern, and it has a very divided parliament,” Houry said.

With Hezbollah’s rivals, the pro-Saudi and pro-US Christian Lebanese Forces, winning new seats and potentially forming an anti-Hezbollah alliance with other candidates, the two could be neck and neck in negotiations to form a new government. This comes less than a year after partisans of both parties clashed in Beirut, killing six people in scenes that resembled the country’s civil war.

And after almost a year of trading blows in the media and on the streets, both parties will now challenge each other in the political arena.

Hezbollah has already insisted on a “national unity government” that includes representatives of all political interests in the country, while the galvanised Christian Lebanese Forces want a government with minimal influence from their political adversaries.

Lebanon is no stranger to political paralysis.

It took politicians 13 months of negotiating to form the current government under Prime Minister Najib Mikati.

New political deadlocks will also come at a steep price, especially with the economy failing, and a caretaker government that will be unable to introduce new laws or do anything beyond the basics.

Houry says if there is no compromise from either side, then “complete blockage” can be expected in the political system.

“Hezbollah, I think, will have to make some compromise. The question will be is how much?”

There may be compromise on some domestic issues, such as corruption, rather than on Hezbollah’s military power or involvement in regional conflicts, he said.

“But another issue is whether or not Lebanese Forces and their allies decide to push things – you can’t corner Hezbollah because you have a majority in parliament. It just doesn’t work that way,” Houry said.

This is a political scenario that is eerily similar to Lebanon after 2005.

At that time, there were two clear factions divided in terms of their position in relation to Hezbollah’s weapons, and the movement’s allies in Syria and Iran. It was a period marked by political paralysis, large-scale protests, assassinations, and even some armed conflict.

“This could be a repeat of post-2005 where they either block things institutionally or through the streets,” Houry said.

“The ball is on their [Hezbollah’s] court whether they decide to facilitate or not.”

Hope for the opposition?

More than a dozen new members of parliament, dubbed the forces of change, have entered the political fray as a result of Sunday’s vote.

The majority are brand new faces, hoping to represent the mood of the popular uprising against the status quo that took place in late 2019.

They have promised to combat corruption, push for sound government policies, and breathe new life into Lebanon’s political sphere.

Around a dozen more candidates broke into parliament to run on somewhat similar anti-establishment platforms.

“These alternative voices will try to raise the bar when it comes to socioeconomic issues that really matter to the people,” the Carnegie Middle East’s researcher Hage Ali explained.

On the other hand, Hage Ali sees Hezbollah and some of its opponents, particularly the Christian Lebanese Forces, attempting to move politics towards sectarian disputes, and issues over weapons, and more “abstract issues that relate little to the problems of daily life in Lebanon”.

Similarly, Houry foresees the ideological diversity of the new anti-establishment members of parliament as posing challenges, which will need to be overcome.

“One way, I suspect, there will be a core group that comes together … some alliances of convenience on an issue basis,” he said.

Some of these new MPs confirmed this to Al Jazeera, explaining that discussions will begin soon to form parliamentary blocs based on common political platforms, while exploring possible alliances for common positions.

All of this could take time, and a political impasse could get in the way of such plans.

“To get there, there is that first main item of business, which is forming a government and having an agenda,” Houry said.

Hage Ali believes that the Christian Lebanese Forces and their allies could attempt to “squeeze out” the anti-establishment lawmakers from political discussion, and then focus broadly on challenging Hezbollah, rather than economic reforms and accountability.

“I think the type of politics that will be introduced by the Lebanese Forces and its allies – particularly its Sunni allies – will pose much more domination of the public sphere,” Hage Ali said.

“That would not allow the independents and civil society groups to have much of a say in how to move things forward … but I hope in the next four years, they will try to pull back the debate to where it should be.”