Who was al-Qaeda’s leader Ayman al-Zawahiri?

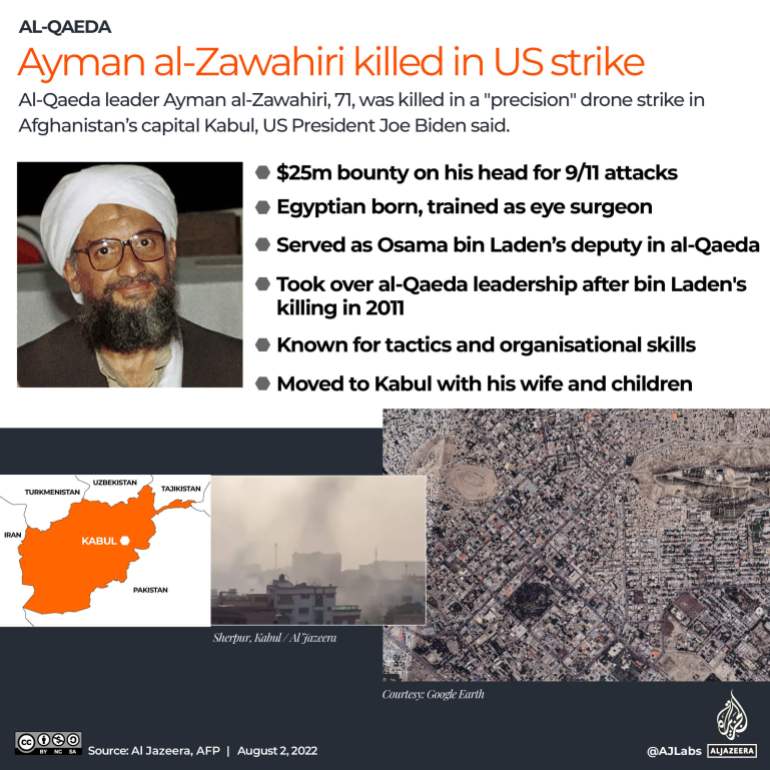

Al-Qaeda leader Ayman al-Zawahiri, linked to 9/11 and attacks that left thousands dead, has been killed in a US drone strike.

Al-Qaeda leader Ayman al-Zawahiri, who has been killed in a US drone attack in Afghanistan, was the group’s key ideologue and strategist, masterminding its global network and planning attacks on the United States.

The 71-year-old Egyptian eye doctor had central roles in the attacks on the US embassies in Kenya and Tanzania in 1998, and the 9/11 attacks on Washington, DC and New York City, where nearly 3,000 people were killed.

Keep reading

list of 4 itemsAl-Qaeda affiliate claims deadly Mali attack

Explosions, gunfire at a military base near Mali’s capital

Burkina Faso’s military government struggles to contain violence

He was named as the group’s leader two months after founder Osama bin Laden was killed by the US in 2011.

While bin Laden came from a privileged background in a prominent Saudi family, al-Zawahiri had the experience of an underground revolutionary. Bin Laden provided al-Qaeda with charisma and money, but it was al-Zawahiri who brought tactics and organisational skills.

“Bin Laden always looked up to him,” Bruce Hoffman, a professor and expert in security studies at Georgetown University, told The Associated Press news agency.

Rise to prominence

Born in 1951 to a prominent Cairo family, al-Zawahiri was a grandson of the grand imam of Al Azhar, one of Islam’s most important mosques.

He was brought up in Cairo’s leafy Maadi suburb, a place favoured by expatriates from the Western nations he railed against.

The son of a pharmacology professor, al-Zawahiri was reportedly arrested at 15 for joining the outlawed Muslim Brotherhood. He also found inspiration in the revolutionary ideas of Egyptian writer Sayyid Qutb, who was executed in 1966 on charges of trying to overthrow the state.

People who studied with al-Zawahiri at Cairo University’s Faculty of Medicine in the 1970s describe a lively young man who went to the cinema, listened to music and joked with friends.

But he was also active in armed opposition circles. He merged his own cell with others to form the group Islamic Jihad and began trying to infiltrate the military – at one point even storing weapons in his private clinic.

Al-Zawahiri first rose to prominence when he stood in a courtroom cage facing charges over the assassination of Egyptian President Anwar Sadat in 1981.

“We have sacrificed and we are still ready for more sacrifices until the victory of Islam,” shouted al-Zawahiri, wearing a white robe, as fellow defendants enraged by Sadat’s peace treaty with Israel chanted slogans.

Al-Zawahiri served a three-year jail term for illegal arms possession but was acquitted of the main charges in the assassination.

During his imprisonment, he was reportedly tortured heavily, a factor some cite as turning him more violently radical.

A trained surgeon – one of his pseudonyms was The Doctor – al-Zawahiri went to Pakistan on his release where he worked with the Red Crescent treating mujahideen fighters wounded in Afghanistan battling Soviet forces.

That was when he became acquainted with bin Laden, who had joined the Afghan resistance.

Taking over the leadership of Islamic Jihad in Egypt in 1993, al-Zawahiri was a leading figure in a campaign in the mid-1990s to overthrow the government in which more than 1,200 Egyptians were killed.

Egyptian authorities mounted a crackdown on Islamic Jihad after an assassination attempt on President Hosni Mubarak in June 1995 in Addis Ababa, Ethiopia.

The greying, white-turbaned al-Zawahiri responded by ordering a 1995 attack on the Egyptian embassy in Islamabad, Pakistan. Two cars filled with explosives rammed through the compound’s gates, killing 16 people.

He was also linked to the attacks on foreign tourists in the city of Luxor, Egypt, in 1997, which left 62 people dead.

In 1999, an Egyptian military court sentenced al-Zawahiri to death in absentia.

By then, he was already helping bin Laden to form al-Qaeda and for years was believed to be hiding along the border between Pakistan and Afghanistan.

Al-Qaeda’s public face

When the 2001 US invasion of Afghanistan demolished al-Qaeda’s safe haven and scattered, killed and captured its members, al-Zawahri ensured the group’s survival. He rebuilt its leadership in the Afghan-Pakistan border region and installed allies as lieutenants in key positions.

He also became the movement’s public face, putting out a constant stream of video messages while bin Laden largely hid.

With his thick beard, heavily-rimmed glasses and a prominent bruise on his forehead from prostration in prayer, he was notoriously prickly and pedantic – picking ideological fights with critics within the camp. Even some key figures in al-Qaeda’s central leadership were put off, calling him overly controlling, secretive and divisive – a contrast to bin Laden, whose soft-spoken presence many fighters described in adoring, almost spiritual terms.

Yet he reshaped the organisation from a centralised planner of attacks into the head of a franchise chain. He led the creation of a network of autonomous branches around the region, including in Iraq, Saudi Arabia, Yemen, North Africa, Somalia and Asia.

In the decade after 9/11, al-Qaeda inspired or had a direct hand in attacks in all those areas as well as Europe, Pakistan and Turkey, including the 2004 train bombings in Madrid and the 2005 transit bombings in London. More recently, the al-Qaeda affiliate in Yemen proved itself capable of plotting attacks on US soil with an attempted 2009 bombing of an American passenger jet and an attempted package bomb the following year.

After bin Laden was killed in a US raid on his compound in Abbottabad, Pakistan, al-Qaeda proclaimed al-Zawahri its paramount leader less than two months later.

In a eulogy for bin Laden, al-Zawahiri promised to continue attacks on the West.

But he watched in dismay as al-Qaeda was effectively sidelined by the 2011 Arab revolts, launched mainly by middle-class activists and intellectuals opposed to decades of autocracy, and as the emergence of the ISIL (ISIS) group in 2014-2019 in Iraq and Syria drew global attention.

Tallha Abdulrazaq, a researcher at the University of Exeter, told Al Jazeera that a “fracturing” of al-Qaeda became increasingly apparent after al-Zawahiri’s takeover.

“While he did inherit the mantle of leadership, he did not inherit Osama bin Laden’s legitimacy as a mujahid leader, or his credibility and legitimacy and charisma amongst the various mujahideen groups,” Abdulrazaq said.

‘Significant blow’

A US drone strike killed al-Zawahiri at a hideout in the Afghan capital, President Joe Biden said on Monday, adding “justice had been delivered” to the families of the September 11, 2001 attacks.

David Des Roches, non-resident senior fellow at the Gulf International Forum, told Al Jazeera that it was a “proud moment” for Biden, “tempered only by the fact that it took place in Kabul, which raises the spectre of the withdrawal from Afghanistan, and, of course, terrorist organisations clearly re-establishing themselves”.

US officials said al-Zawahiri’s family moved to Kabul earlier this year, and then the al-Qaeda leader joined them. He did not leave the building but was seen often on the balcony, where he was eventually killed.

Colin Clarke, research director at the Soufan Group, a global security firm, told Al Jazeera that his death would be a “significant blow” to the group, and said his presence in Kabul raised questions over his relationship with the Taliban.

“It tells us he’d gotten far more comfortable over the past year since the Taliban took over,” Clarke said.