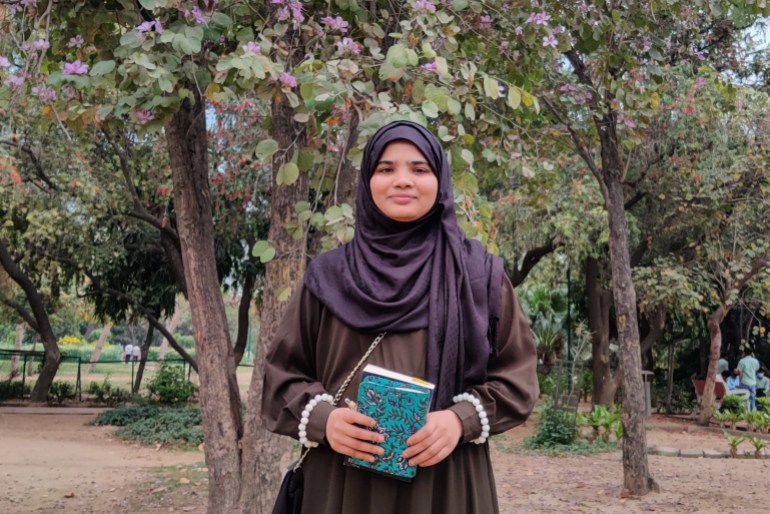

‘Becoming visible’: India’s first female Rohingya graduate

Tasmida Johar is happy she was able to study despite all the odds but wishes other women in her community also had the opportunity.

New Delhi, India – Tasmida Johar, India’s first woman graduate from the displaced Rohingya community, says she is going through a “conflicting feeling” these days.

“I feel happy about these headlines, ‘first this, first that’, but at the same time, it also makes me sad. I am happy because this is my achievement, of making it this far,” she told Al Jazeera as she sat in a public park in a predominantly Muslim neighbourhood of capital New Delhi.

Keep reading

list of 4 itemsIndia denies it will provide homes to Rohingya in capital

Rohingya families in Kashmir fear separation as India cracks down

Will the UN’s plea to help Rohingya refugees be answered?

“But it makes me sad that I am the first one to do when so many Rohingya women wanted to come to this position but they could not.”

The Rohingya, a mainly Muslim minority from neighbouring Myanmar, are a persecuted community that saw a brutal military crackdown in 2017, which the United Nations said was conducted with a “genocidal intent”.

Most of the Rohingya fled to Bangladesh, turning its Cox’s Bazar district into the world’s largest refugee camp with more than a million refugees living in cramped makeshift homes made of bamboo and tarpaulin.

Nearly 20,000 Rohingya are registered with the United Nations as refugees in India, some of them arriving even before 2017. More than a thousand of them live on the outskirts of New Delhi.

Since 2014 when a Hindu nationalist party came to power in India, the community has also faced hate speech and attacks, with the government last year saying the Rohingya will be held in detention camps until they are deported back to Myanmar.

India is not a signatory to the UN’s 1951 Refugee Convention or its 1967 Protocol, nor does it have a national refugee policy in place.

Twice displaced

Johar, 26, said she was displaced twice. Born in Myanmar as Tasmin Fatima, her parents were soon forced to change her name.

“My parents had to change my name because in Myanmar, you can’t go to school and avail education if you don’t have a Buddhist name,” she said.

In Myanmar, she said, if the authorities found out that a Rohingya owned a business, they were “attacked and jailed”.

“My father Amanullah Johar had a business of exporting and selling fruits and vegetables. Very often, he was detained and only released after the police took some money from him,” she told Al Jazeera.

Johar said schools in Myanmar also discriminated against them.

“If you bagged the first position in Burma schools, they didn’t give you the prize if the first-rank holder was not a Buddhist,” she said, using the older name for Myanmar before it was changed in 1989.

“Roll numbers were allotted to Buddhist children first and then to us. We were not allowed to speak loudly, always had to sit at the back of the class. We were prohibited from wearing scarves (hijab) in schools.”

As the persecution increased, the family left Myanmar in 2005, driving in a car to the border and taking a boat to Cox’s Bazar.

Having to start from scratch again, her father began working as a daily wage labourer at 64 while her mother, Amina Khatoon, 56, started working in a local factory.

Even though Johar had studied till third grade in Myanmar, she had to start from the first standard all over again. But as she assimilated into new cultures, she started learning Bengali, Urdu and English apart from Rohingya and Burmese that she already knew. In India, she would later pick up Hindi, too.

In 2012, the community faced targeted violence in Bangladesh. Johar’s father was briefly arrested, too.

The family decided to move to India, arriving first in Haryana, a north Indian state bordering Delhi, where they could not find access to proper education. So they came to the national capital and settled in southeast Delhi’s Kalindi Kunj camp.

‘Travelling in a bus was our resistance’

Johar said she had many inhibitions when she came to India. She was scared because she was a Rohingya. She also did not know Hindi.

“I didn’t want my identity to be revealed to all the children at school because neither did I want any special treatment nor did I want to face any indifference or being called terrorist and other names. Rohingya have faced these remarks far too many times in this country. Hence, I kept to myself most of the time,” she said.

Tasmida travelled to school and college in a bus. This caused concern for her mother who would stand by the road, waiting for her to arrive.

“Many times, I didn’t get a seat on the bus. But this was nothing compared to what we had faced. The success you earn after hardships feels different. Travelling in a bus was our little resistance,” the political science graduate from Delhi University told Al Jazeera.

Johar pointed out the fears among her community as they went about their lives in India.

“Rohingya refugees think if they send their girls outside to study, what if the government picks them up? What if they are kidnapped, raped or sold? This is a projection of what transpired in Burma. Hence, there is a perpetual anxiety among them for their children,” she said.

Her neighbours would ask her parents: “What will you do by making her study?”, “What if something happens to her?”

While Johar said such remarks were common, their attitude changed when they saw her succeed in her studies.

“People from my community saw the headlines and realised they can also be visible. There was a little shift in their mindset and suddenly I started getting comments like ‘we knew she could do this’ and ‘our daughter will also become like yours’,” she said, her face flushed with pride.

Mizan Hussain, 21, is among the youngsters taking inspiration from Johar. “The reason my mother supports me is because of Tasmida. She understands it now and gives me permission to go out and study more.”

Johar says most of the children in her neighbourhood are studying one way or the other: either in schools, at the camps or through home tuitions.

Khatoon thinks her daughter should study further and work for her community. “She should be the voice of all the vulnerable and oppressed women and children who cannot raise their own voice,” she said.

“Refugees like us, we don’t have anything to pass on to our children. The only thing we can give them is ‘taaleem’ (education).”

Johar is among 25 refugee students selected by the UNHCR-Duolingo programme to help disadvantaged and academically bright individuals pursue higher studies. She is waiting for an acceptance letter from the Wilfred Laurier University in Canada.

She says she wants to become a human rights activist in the future.

“I want to fight for the rights to education, health of the oppressed women, and raise [my] voice against trafficking of young girls. My dream is to go to the International Court of Justice and tell them about the plight of Rohingya refugees. It is only befitting that a Rohingya takes the mic and speaks the truth as we are being wiped from many privileged spaces and stories,” she said, her voice firm.