War comes home to Russia: Pro-Kyiv fighters seek Putin’s downfall

Russia has been jolted by one of the most daring incursions, allegedly carried out by groups including Russian nationals.

Kyiv, Ukraine – This week, a man with yellow and blue plastic bands on his helmet and camouflage uniform was filmed riding atop an armoured vehicle.

The colours are unmistakably those of the Ukrainian national flag, but the man – seen in the video posted on his military unit’s Telegram channel on Tuesday – is a Russian national.

Keep reading

list of 4 itemsLeader of anti-Putin force says expect more Russian border raids

Russia claims 70 attackers killed in cross-border Belgorod raid

Brazen raids into Russia aim to stretch forces thin: Analysts

He chose to fight for Ukraine, and brought the war home on Monday, to the western Russian region of Belgorod that had already been shelled and attacked, apparently by Ukrainian drones, for months.

The unidentified man in the video is part of the Russian Volunteer Corps, a military unit formed by fugitive far-right nationalists forced out of Russia. The group only accepts Russian nationals as members.

Some of the Corps’ fighters volunteered to join Ukrainian forces in 2014, after Moscow annexed Crimea and incited separatist revolts in the southeastern Donbas region, and some joined after the latest war began in February 2022.

The Corps consists of “dozens of fighters”, Fortuna, as one of the group’s founders calls himself, told a news conference in October.

Two months earlier, they became part of the International Legion of Ukraine, a group of volunteers from all over the world that reports to Ukraine’s defence ministry.

Moscow, which is reluctant to publicly admit Russian nationals are fighting for Ukraine, blamed Kyiv for the incursion, a claim which was quickly denied.

Kremlin spokesman Dmitry Peskov, questioned if the attackers were ethnic Russians, said, they are “Ukrainian fighters from Ukraine. There are many ethnic Russians living in Ukraine. But they are still Ukrainian militants”.

The Ukrainian defence ministry – along with other officials in Kyiv – initially distanced themselves from the Corps.

Its first confirmed raid on Russia took place on March 2, after they entered two villages in the border region of Bryansk.

The Corps then released a video of its fighters standing outside a village hospital and urging Russians “to riot and fight”.

Bryansk Governor Aleksander Bogomaz said they killed a civilian and wounded a 10-year-old. Russian President Vladimir Putin cast the raid as a “terrorist act”.

Mykhailo Podolyak, an aide to Ukrainian President Volodymyr Zelenskyy, called those claims a “classic deliberate provocation”.

But Ukraine’s defence ministry denied a role in organising the raid.

“These are the people who fight with arms against Putin’s regime and supporters. Perhaps, Russians are beginning to wake up,” military intelligence spokesman Andriy Yusov said.

A bigger bang

On Monday, the Corps started its second, far more daring incursion in Russia.

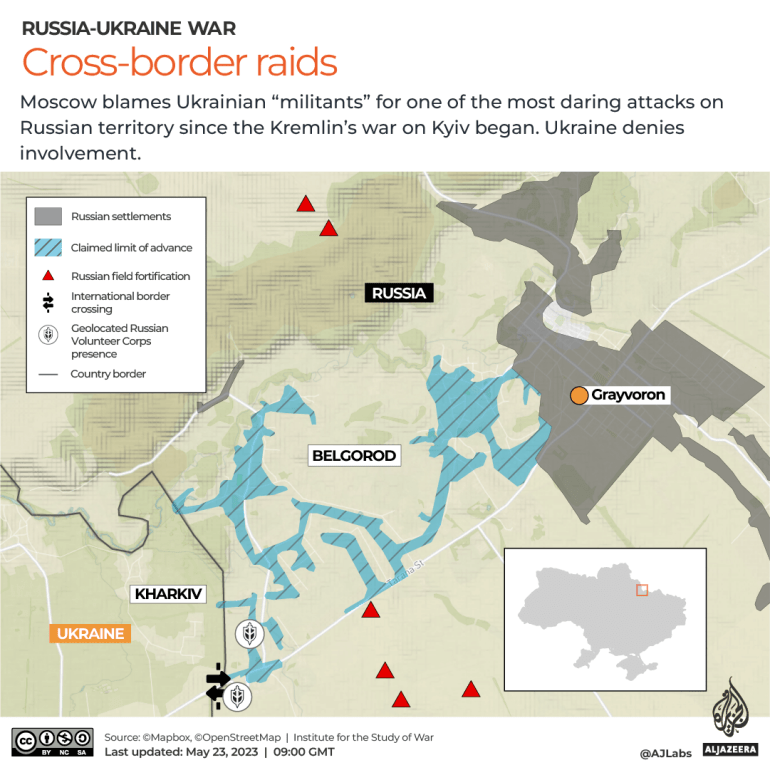

Along with The Freedom of Russia Legion – also known as the Liberty of Russia Legion, a military unit which includes ex-Russian prisoners of war who have switched sides, they stormed a border checkpoint and spilled into the Grayvoron district in Belgorod.

The district is surrounded by Ukrainian territory on three sides, but its administration failed to protect it with trenches, artillery and anti-tank installations.

The invaders had two tanks and 10 armoured vehicles and were backed by light drones.

They killed a border guard, one of the fighters told the Novaya Gazeta daily on condition of anonymity, reportedly captured one more and reached three villages, where they started building fortifications and clashed with Russian forces.

The incursion highlighted the vulnerabilities of Russia’s border regions, military analysts say.

“It showed that Russia has no reserves in border regions and weak reserves in the operational depth, which means that the residents of all districts bordering Ukraine are in immediate danger and must be evacuated,” Nikolay Mitrokin of Germany’s Bremen University told Al Jazeera.

The Corps claimed to have occupied a “piece” of Russia.

“The situation in a small yet our own piece of Motherland is so far alarming, and there’s a need to clean up,” said the caption under a video showing a Corps fighter.

By Monday night, they had attacked the local headquarters of the interior ministry and the FSB, Russia’s main intelligence agency.

On Tuesday, Russia claimed to have killed “70 Ukrainian terrorists”, roughly the number of all Corps fighters.

The group responded with a video showing several fighters with blurred faces and three armoured vehicles.

This time, Kyiv did not deny ties to the group.

Their goal is “to push the enemy in order to create a strip of safe land to protect Ukrainian civilian population”, intelligence spokesman Andriy Yusov said on Monday.

A more immediate and important goal is to force the Kremlin to deploy forces to the border regions of Belgorod, Bryansk and Kursk.

The deployment will surely decrease Russia’s military might in Ukraine before the long-awaited counteroffensive, observers say.

“This is a risk for Russia to get a good screw-up on the front line,” Kyiv-based analyst Igar Tyshkevich told Al Jazeera.

Hiding in Ukraine

Far-right, ultranationalist and white supremacist groups mushroomed in Russia in the early 2000s, creating a decentralised movement that involved tens of thousands.

They marched in urban centres, killed and wounded hundreds of migrant workers from Central Asia and the Caucasus, and even hatched plans to topple Putin’s government and create a neo-Nazi “Fourth Reich”.

Ukrainian far-right groups developed in parallel, but their ideology was different, Tyshkevich said – anti-imperialistic “in principle”, less racist and xenophobic.

However, in terms of organisation, the Russian influence was formative.

Before 2014, the movements in both nations were “amorphous” youth subcultures that formed a “system of connected vessels”, Vyacheslav Likhachev, a Kyiv-based expert on ultranationalism, told Al Jazeera.

When the Kremlin cracked down on the far right, many activists moved to Ukraine “to hide in the familiar linguistic and cultural environment and to keep indoctrinating and passing their experience to their Ukrainian brethren”, he said.

After 2014, the flight became a flood.

Most of the refugees quit politics, but some kept positioning themselves as “the most right Russians” who were against Putin and European liberalism, he said.

White Rex

The founders of the Corps were among them – and they still want to topple Putin.

“Russia’s collapse will allow us to return home,” Denis Kapustin, the Corps founder, told the news conference in October. “We will facilitate the complete and absolute breakdown of the political order in Russia.”

The burly 39-year-old calls himself a seasoned skinhead, football fan and organiser of mixed martial arts fights.

He lived in Germany, where police described him as “one of the most influential activists” of the far-right movement.

After returning to Russia he moved to Ukraine in 2017, where he developed ties with Azov, a regiment known for defending the southern Ukrainian city of Mariupol last spring.

Some of the Azov members – including fugitive Russians – espoused far-right views. The US Congress banned the regiment in 2018 from using Washington-supplied military aid.

What next?

The Ukrainian far-right groups and their newly-recruited Russian members were highly visible before the war.

They organised rallies, assaulted Roma encampments, beat up pro-Russian politicians and LGBTQ activists, clashed with police – and almost always walked away scot-free.

But since the war began, their influence waned.

“The [Ukrainian] society tilted to the right, but on the other hand, the extreme shifted towards the public in terms of reduced radicalism,” analyst Tyshkevich said.