Biden’s Middle East policy not much different than Trump: Expert

Professor John Esposito also tells Al Jazeera that despite growing understanding of Islam in the US, Islamophobia remains.

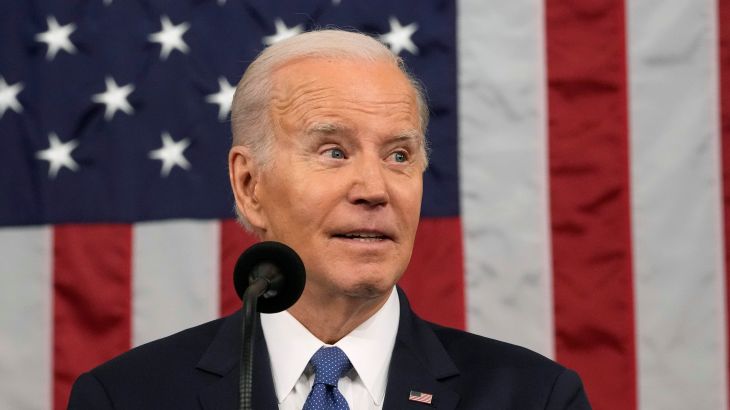

US policies on the Middle East and the wider Muslim world have not shifted significantly under Joe Biden, a leading Western scholar on Islam has said, despite the United States president and his top officials promoting human rights and a message of tolerance globally.

John Esposito said in an interview with Al Jazeera’s new Digital series Centre Stage that there has been growing awareness of Islam in the US, with more university students learning about the religion.

Keep reading

list of 3 itemsUS nuclear subs to dock in South Korea to deter Pyongyang: Biden

‘Ironclad’: Biden, Marcos Jr affirm US-Philippines security ties

But that has not meaningfully affected US foreign policy, said Esposito, a distinguished professor of religion, international affairs and Islamic studies at Georgetown University in the US capital.

“When you look at the policies of the [Biden] administration, sadly – sad to say, from my point of view – there’s no significant difference when it comes to their approach to the Middle East or to the Muslim world,” Esposito told Al Jazeera’s Soraya Salam on Wednesday.

Biden took office in early 2021 after his predecessor, Donald Trump, was accused of using Islamophobic rhetoric and pursuing policies that harmed Muslims. This most notably included a travel ban for citizens of several Muslim-majority countries.

Biden reversed the travel restrictions, which came to be known as the “Muslim ban”, on his first day in the White House.

He has since appointed several Muslims to his administration, including Rashad Hussain as envoy for international religious freedom.

The moves came after Biden, as a candidate in 2020, had released a platform for Muslim-American communities that vowed to combat bigotry and “discriminatory policies”.

But on foreign policy issues that impact many Muslims worldwide, the Democratic president has largely stuck to Trump’s approach, especially in the Middle East.

Biden has kept the US embassy in Israel in Jerusalem; he has not reversed Trump’s recognition of Israel’s claimed sovereignty over Syria’s occupied Golan Heights, and he continues to enforce his predecessor’s “maximum pressure” campaign of sanctions against Iran.

“There’s no significant shift,” Esposito stressed.

Words vs actions

Esposito also noted that former President George W Bush visited a mosque days after the September 11, 2001 attacks on New York City and Washington, DC and “made a very nice statement” about Islam but went on to invade and occupy Iraq.

Despite leading the so-called “war on terror”, which saw rampant abuses against Muslims around the world, Bush verbally rejected bigotry against Arabs and Muslims early in his administration, stressing that the US is not fighting Islam.

Following the September 11 attacks, Esposito – who is also the founding director of Georgetown University’s Alwaleed Center for Muslim-Christian Understanding – had advised then-senator Biden and other US legislators on Islam and the Middle East.

He said Biden was “open” and looking to deepen his understanding of the issues at that time, but many lawmakers did not take the Middle East seriously before then.

“Most senators or congresspeople had somebody on their staff that handled the Middle East, and so they would then just rely on that person who would then write a report for them,” Esposito told Al Jazeera.

Esposito said jokingly that he owes his decades-long career, much of which was dedicated to promoting understanding of Islam – to the 1979 Iranian revolution and its main figure, former Supreme Leader Ruhollah Khomeini.

He said that while Muslims at that time were not very visible in the US, they were often portrayed in a negative light in the media.

“There was [an] immediate equation that this is what their religion is like – that is the TV every day showing people shouting, ‘Death to America,'” Esposito said, referring to footage of protests in the Middle East.

While awareness of Islam as a religion in the US has come a long way since then, Esposito said a significant number of Americans still do not have a good understanding of Islam.

Another issue he outlined is what he called the “globalisation of Islamophobia”.

“I think that the globalisation of Islamophobia has been missed in the sense that, in fact, Islamophobia has grown in Europe – in countries like Austria, in the UK, in Germany – and it grows in countries where they don’t have many Muslims,” he said.