What does Erdogan’s re-election mean for Turkey-Gulf relations?

Economic and defence deals, along with the Turkish president’s personal ties with regional leaders, will boost relations.

President Recep Tayyip Erdogan’s victory in Turkey’s unprecedented run-off on May 28 was welcomed by officials in the Gulf Cooperation Council (GCC) as it would bring a sense of continuity and strengthen relations between Ankara and the bloc as well as its six members.

Qatar’s Emir Sheikh Tamim bin Hamad Al Thani was the first foreign head of state to congratulate Erdogan, who has taken office for his third presidential term, and other Gulf leaders quickly followed suit, expressing their desire to bolster ties with Turkey.

Keep reading

list of 4 itemsWorld leaders congratulate Turkey’s Erdogan on election win

After Turkey election win, what problems does Erdogan face next?

What does re-election of Erdogan mean for Turkey and the world?

Erdogan, 69, whose two-decade rule will be extended for another five years, is expected to visit the Gulf soon in a reflection of how important GCC members have been to Turkey’s foreign policy agenda.

Between now and 2028, the GCC states can expect business as usual in their dealings with Ankara.

Turkey’s strong alliance with Qatar will likely continue to deepen while Erdogan also looks to expand relations with Saudi Arabia and the United Arab Emirates (UAE) as Ankara’s rapprochement with Riyadh and Abu Dhabi continues to gain speed.

“It is likely that the Turkish-Gulf relations will continue to have a personalised nature as it has been in the past two decades,” Sinem Cengiz, a researcher at Qatar University and Arab News columnist, told Al Jazeera.

“Therefore, the next five years of Erdogan’s tenure are likely to bring a continuation of the personalities’ cooperation on a range of areas.”

Erdogan’s re-election was a relief to many Gulf officials because his challenger Kemal Kilicdaroglu would have likely changed Turkey’s foreign policy towards the GCC in ways that could have undermined their interests. Qatar, in particular, had reason to fear a downgrading of its relationship with Ankara had Kilicdaroglu won.

“The opposition candidate was convinced that Erdogan had struck certain off-the-record deals with Gulf capitals – and thus espoused very Gulf-sceptic views regularly,” Batu Coskun of the Sadeq Institute told Al Jazeera.

Economic stability

Ankara will continue placing much value on its economic, political and security ties with the wealthy GCC countries, important to Turkey’s trade and defence markets.

Closer Emirati-Turkish economic links will also provide the two countries, which have two of the Middle East’s largest economies, opportunities to unlock vast amounts of investment that can help both economies grow.

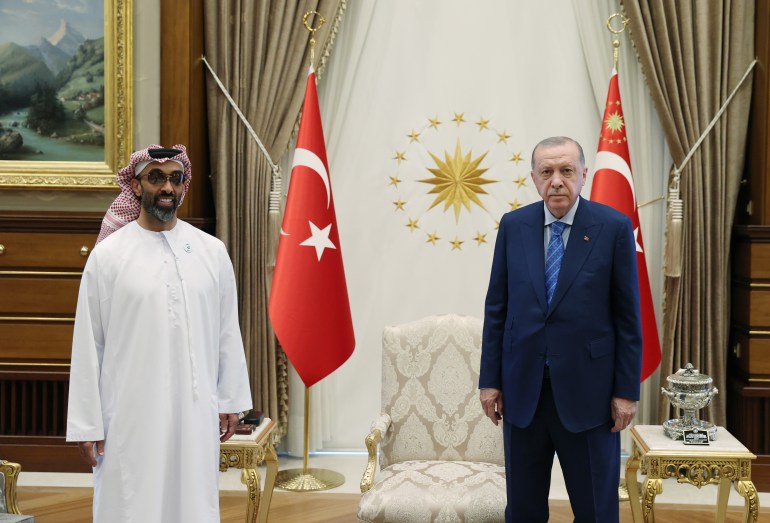

A few days after Erdogan secured another term, Turkey and the UAE ratified a cooperation agreement that aims to increase their bilateral trade to $40bn in the next five years. Thani Ahmed al-Zeyoudi, the UAE’s minister of state for foreign trade, tweeted: “This deal marks a new era of cooperation in our long-standing friendship.”

Negotiations for the deal had started in 2021 when then UAE Crown Prince Sheikh Mohamed bin Zayed Al Nahyan visited Ankara, paving the way for a thaw in relations after years of tension.

“The prospect of hard cash from the Gulf will continue being a major incentive for Ankara, which is facing a persistent currency crisis,” said Coskun.

“Turkey presents itself as a financial and business hub for the Gulf investors to invest in diverse sectors,” explained Cengiz. “I assume that investment in Turkey could be one of [the] areas [in which] we may see a competition among the GCC states, namely Saudi Arabia and the UAE.”

For Gulf Arab states, deeper ties with Turkey are important for their economic diversification agendas. Across a host of sectors, from entertainment to tourism and food production, Turkish companies can play an important role in helping GCC states transition away from their dependency on hydrocarbons.

Turkish firms, especially in the construction sector, have long penetrated Gulf markets and contributed to the growth of megaprojects, from airports to highways and stadiums to high-rises. Recently, a group of executives representing roughly 80 Turkish building companies met with Saudi Aramco in Ankara for discussions about $50bn of potential projects in Saudi Arabia.

There is also the defence sector, with developing its indigenous defence industry a significant pillar of Saudi Arabia’s Vision 2030 strategy.

“Turkey’s burgeoning defence industry could be integrated into the Saudi Vision 2030,” according to Coskun. “This could materialise in the form of joint production, technology transfer and training programmes. Major investments could see Turkish defence industry production having a leg in Saudi Arabia.”

Turkey’s relations with Syria

An important issue in Turkey-GCC relations is Syria. With Damascus having regained full-fledged membership in the Arab League last month following more than 11 years in the diplomatic wilderness, Ankara is also seeking to reconcile with President Bashar al-Assad’s government.

But one of the factors that make an Ankara-Damascus normalisation deal tricky is the status of the People’s Protection Units (YPG) in northern Syria. Turkey will want some security guarantees regarding the YPG, which it considers the Syrian wing of the PKK. Turkey, the US and the EU recognise the PKK as a terrorist organisation.

Riyadh and Abu Dhabi have been encouraging al-Assad’s government to accept the YPG-dominated Syrian Democratic Forces (SDF) under Damascus’s sovereign control as part of the force’s integration into the Syrian state. In this sense, Gulf capitals, especially Abu Dhabi, could “add a Gulf track to the existing Moscow track which is being used to facilitate [Turkish-Syrian] talks”, said Coskun.

There are important questions about how any possible future ties between Ankara and Damascus could affect the Turkey-United States alliance. Given that Washington does not want to see its allies and partners in the Middle East and North Africa recognise al-Assad as a legitimate Arab president, Washington is not likely to welcome Ankara reopening formal ties with the Syrian government.

Within this context, Turkey may benefit from certain GCC states rehabilitating al-Assad’s image first, making it less controversial from the West’s perspective for Ankara to reconcile with Syria.

Coskun told Al Jazeera that Ankara will “seek to deflect pressure from the US over normalising with al-Assad by arguing … a regional consensus over Assad’s return to the global stage”.

Rapprochement and rebuilding

Relations among countries in the Middle East and North Africa have evolved a great deal since 2020. It was not long ago that Saudi Arabia and, even more so the UAE, were on negative terms with Turkey. Conflicting interests regarding a host of crises in the post-Arab Spring period such as Egypt, Libya and Tunisia, as well as the 2017-2021 blockade of Qatar, caused friction between Ankara on one side and the Saudi-UAE axis on the other.

Yet, since about 2020, Turkey’s relationships with Riyadh and Abu Dhabi have markedly improved.

“Erdogan is now starting a new chapter, opposite to how it was approximately 10 years ago when the Arab Spring started,” said Dania Thafer, executive director of the Gulf International Forum.

“Now, similar to the GCC states, Ankara’s strategy is more pragmatic with economic development as a main imperative rather than politics led by ideology.

“In his last term, he rebuilt relations with Saudi Arabia and the UAE, and will continue on that path. Turkey will likely sign several agreements in commerce, defence and security with both the UAE and Saudi Arabia among other GCC states.

“From a political perspective, rebuilding relations with Turkey is an alternative approach to counterbalancing Iranian influence in the region.”

During Erdogan’s next five years, experts argue that there is every reason to expect these rapprochements to gain even greater momentum. In particular, Turkish drone sales to these two GCC members will further strengthen relationships that began to mend a few years ago.

“Ankara-Abu Dhabi ties appear on course to continue expanding,” said Coskun. “The recent mutual ratification of the Turkey-UAE comprehensive partnership agreement is a clear indication of this. The UAE also made a significant purchase of Bayraktar TB-2 UAVs last year. Likely, Abu Dhabi will become a major market for Turkish defence industry exports.”

Coskun added that “the same prospect is true for Saudi Arabia – yet we are yet to see a sale of TB-2s to Riyadh. Given that Qatar, the UAE and most recently Kuwait made agreements to purchase the famed UAVs, Saudi Arabia appears a very likely candidate. This new period is likely to see more robust relations between Ankara and Riyadh – particularly based on the defence industry.”