The ‘complex’ legacy of US professional wrestling’s Iron Sheik

Hossein Khosrow Ali Vaziri, who died on Wednesday, both perpetuated and transcended stereotypes in his role as wrestler.

Hossein Khosrow Ali Vaziri, an Iranian-born athlete who rose to fame in the 1970s and 1980s, died on Wednesday at the age of 81.

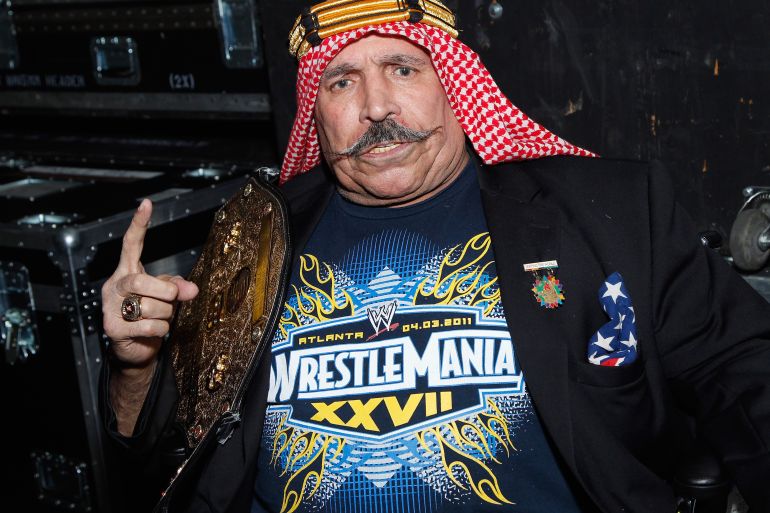

Known as the “Iron Sheik”, Vaziri made a name for himself in the theatrical world of United States professional wrestling before becoming a social media fixture later in life. His most notable outings came as part of the World Wrestling Federation (WWF), which later became the World Wrestling Entertainment (WWE).

Keep reading

list of 3 itemsQatar Pro Wrestling attracts former WWE champs

WWE pushing diversity at Las Vegas mega event SummerSlam

A statement announcing Vaziri’s death, posted to his Twitter page, said the wrestler “transcended the realm of sports entertainment” with “his larger-than-life persona, incredible charisma and unparalleled in-ring skills”.

Longtime fans and media observers also recalled a legacy defined by contradiction. Often seen wearing a traditional ghutrah headdress and pointed-toe boots, Vaziri represented a mishmash of Middle Eastern stereotypes in his role as a heel — or villain — on the wrestling circuit.

Critics have commented that his performances reflected the geopolitical tensions of the time, if not outright mainstream xenophobia. At times, he even wielded an ancient Persian club.

But despite the over-the-top theatrics of televised professional wrestling, those stereotypes could transcend into a form of representation, said William Lafi Youmans, associate professor of media and public affairs at George Washington University.

“He was always willing to be the villain in the cultural moment and sort of exploit the politics of xenophobia,” Youmans told Al Jazeera, pointing to when Vaziri assumed the moniker “Colonel Mustafa” during the 1990-91 Gulf War.

WWE is saddened to learn that Hossein Khosrow Ali Vaziri, known the world over as WWE Hall of Famer The Iron Sheik, passed away on Wednesday, June 7, at age 81.

WWE extends its condolences to The Iron Sheik’s family, friends and fans.https://t.co/FGE0yKeuWA pic.twitter.com/yVLpLObxFA

— WWE (@WWE) June 7, 2023

Vaziri had first entered professional wrestling as the perhaps even more crassly named “The Great Hossein Arab” before settling on his moniker, the Iron Sheik. His career flourished in the wake of the 1979 Iranian revolution and the US hostage crisis in Tehran, when he often faced off against the “All American” wrestler Hulk Hogan.

Nevertheless, in a time when US popular culture was defined by cardboard cutouts of Middle Eastern and Russian baddies, the Iron Sheik’s charisma and more developed back story had its own beguiling appeal, said Youmans.

“It’s not as simple as: There’s a negative stereotype and then I’m going to be crushed by that,” Youmans explained, reflecting on what the Iron Sheik meant to him personally.

“As a young Arab American, the negative stereotypes are all around us. So you can kind of fight back in some ways through who you choose to support. So I was a fan of the Iron Sheik as a villain.”

Born in Damghan, Iran, to a working-class family, Vaziri gained local prominence as an amateur Greco-Roman wrestler and competed nationally. He later served as a bodyguard for the last shah of Iran, Mohammad Reza Pahlavi.

Vaziri told Yahoo Sports in 2013 that he fled Iran in the late 1960s after the death of the famous wrestler Gholamreza Takhti. Vaziri maintained that Takhti was murdered for his anti-government views, although the government maintained it was suicide.

In the early 1970s, Vaziri served as an assistant coach to the US Olympic wrestling team, before breaking into televised US professional wrestling, initially for the American Wrestling Association and then the WWF.

Embodying the geopolitical camp of the time, he would spit when “USA” was said aloud. He often chanted “Russia number one! Iran number one!” when teaming up with wrestler Nikolai Volkoff, a heel wrapped in Soviet Union stereotype.

RESPECT THE LEGEND FOREVER 😢 pic.twitter.com/Cr6CC9pXSO

— The Iron Sheik (@the_ironsheik) June 7, 2023

Seeing Iran-US tensions play out in the WWF ring — and outside of bleak news cycles — offered something of release to viewers, said Niki Akhavan, chair of the department of media and communication studies at The Catholic University of America.

“It’s bizarre to say it, but it was a relief to see it in that context, because you could still root for him but not be seen as sort of anti-American. Because it was all kind of in fun. Like, you knew that it was a joke,” Akhavan told Al Jazeera. “I feel like he embraced being the heel. For me, as an Iranian, I just love that.”

Akhavan explained that Vaziri’s wrestling character represented “a different way of being an Iranian in American culture, where you typically have to choose an ‘either/or’. You’re either the terrorist Iranian or you’re the Iranian who’s calling for sanctions and war on your own country.”

“He’s kind of this complex, contradictory guy who doesn’t fall into any of it … or does fall into all of it,” she said.

Inducted into the WWE Hall of Fame in 2005, Vaziri experienced a sort of renaissance in his later years as he took his caustic one-liners to social media. At the same time, he contended with personal tragedy, including the 2003 murder of his daughter in a domestic violence incident.

In his final Twitter post, just 15 hours before the statement about his death, he cursed the wildfires ravaging Canada.

On this solemn occasion, Hulk Hogan is trending only because of how much the Iron Sheik hated him.😂

RIP, Sheik. You are the legend forever.🙏🏼🙌 pic.twitter.com/nHjbnIgaOv

— Huckster Finn 🐬 (@FinnHuckster) June 7, 2023

His death brought a lot to mind for Josh Hamzehee, whose play Burnt City: A Dystopian Bilingual One-Persian Show explores questions of biracial identity, masculinity and the playwright’s own relationship with his Iranian father.

At times in the show, Hamzehee embodies the Iron Sheik, a figure he grew up “not necessarily idolising” but who nevertheless played a “big factor in how I understood my own Iranian heritage”.

“It’s been interesting trying to get into what that mindset is, of someone who has to repeatedly be a villain and see their own heritage as a villain and try to embrace that,” Hamzehee said. “It’s a lens that has allowed me to understand myself a lot. But it is understanding myself through my Iranian heritage — through how maybe the West has put it out for me.”

For Hamzehee, that conflict was perhaps best embodied in the infamous 1984 match between the Iron Sheik and Hulk Hogan.

“At the end of it, you think he’s going to win because he has Hogan in his finishing hold, but then Hogan breaks out of it and leg drops him,” he said. “I think that’s the in-between space I always find myself at when I think about him.”