Hope and hunger

Life at a crossroads in Madagascar's arid south.

Androy Region, Madagascar - Sambo recounted the story of an elderly woman who collapsed while searching for wild tuber in the fields surrounding the village of Berenty in Madagascar’s sprawling 111 square-kilometre Grand Sud.

Her death was just one scene of desperation that has defined the last year for the village chief.

About 30 people living in the community of about 630 died during that period, he said, which represented, at least to date, the nadir of the worst drought the region had seen in the last 40 years.

“If it weren't for the nuns in Amboasary to help them, I can’t imagine the next episode,” he said, referring to aid workers in the closest town, a rugged 45-minute drive away along uneven cactus-lined hills. “If the WFP [World Food Programme] didn’t come earlier, I couldn’t imagine.”

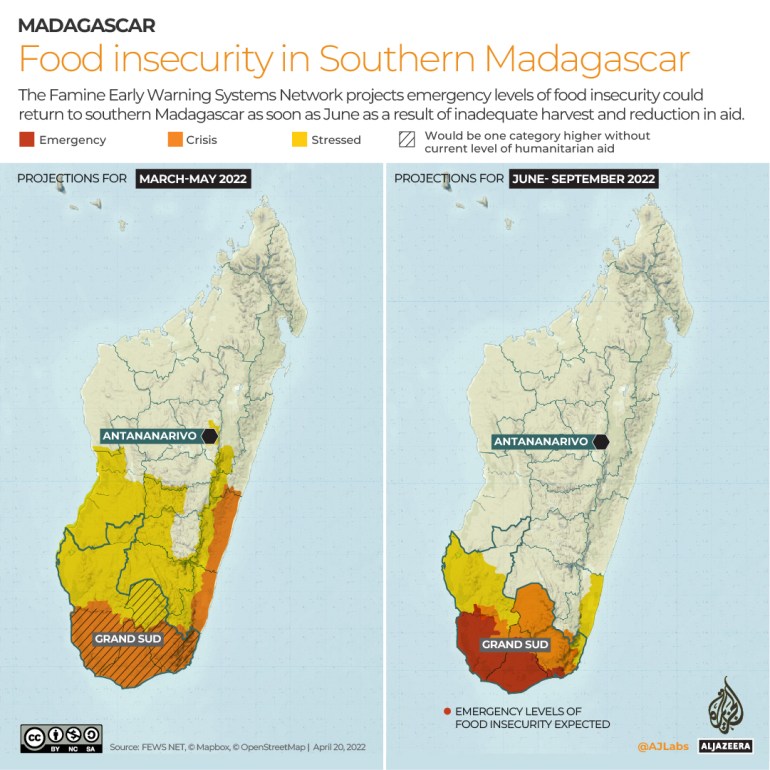

An influx of aid brought a measure of stability to the Grand Sud, where a paltry harvest in May of 2021 left 1.6 million people on the edge of hunger, with 30,000 facing immediate life-threatening conditions and humanitarian officials warning of "catastrophe".

At the time, the WFP warned the situation could become the world's first famine powered not by conflict, but instead the first "climate change famine".

The outlook is slightly better this year, but with this season’s rainfall still expected to be below average - the sixth year of similar conditions of the last seven for the beleaguered inhabitants - any upcoming reprieve is feared to be short lived.

For Sambo, it is difficult to consider what comes next.

His hope for the coming months had been planted as seeds sown in the ground in Berenty village. He longed for the crop yields from the upcoming harvest - which will be completed in May - to lead the residents out of the suffering of recent months and the near-total reliance on humanitarian aid.

But when the rains finally did come, they brought hope to some and destruction to others.

"The famine should have been fought, the rain has fallen," he said, referring to Cyclone Emnati, which tore through the region in late February.

"Unfortunately, all our crops have been decimated by the waters," he said, holding his Panama hat in one hand and pointing to a field of caked soil. "And the sun is starting to rise up again, so the suffering is starting over."

Anything approaching more long-term solutions remains beyond the horizon in the Grand Sud, which includes particularly arid stretches in Androy, Anosy and Atsimo-Andrefana regions.

Climate scientists warn that rising temperatures will continue to worsen cycles of food insecurity and hunger in southern Madagascar, which accompany periods of drought projected to become more severe.

The emergency of recent months has also shed light on the more provincial underpinnings of the insecurity, in what international observers have described as a "crisis of development" and human rights grown out of years of negligence. More than two-thirds of Madagascans live in poverty, with the rate at about 90 percent in the south.

In Berenty, sitting in the doorway of her sparse wood-framed home, 50-year-old Selambo, a mother of four, knows all too well the reality of existence at the crossroads of forces far beyond her control.

Selambo said her adult children are married and have moved on; she has no husband or crops, "not even a chicken".

Weakness from undernourishment has left her unable to work as a sisal cutter, a job that involves shoring off thousands of fibrous leaves used to make ropes and mats. She relies on humanitarian handouts, but sometimes begs for corn at the local market.

When the begging is unsuccessful, she scrounges for leaves to eat.

"My future?" she said, grimacing and touching her stomach. "I am hungry."