Surging tides

How sea-level rise could sever a vital transport link in Canada

This story was produced with the support of Internews’s Earth Journalism Network.

Chignecto Isthmus, Nova Scotia, Canada - Seven years ago, the sun, moon and Earth aligned to produce a tidal surge in the Bay of Fundy, pushing the sea within centimetres of a national rail line connecting the eastern Canadian provinces of Nova Scotia and New Brunswick.

The water lapping at the edges of the train tracks marked the zenith of an 18-year astronomical cycle due to repeat in about a decade’s time – and fuelled concerns among locals conscious of the ever-present flood risk.

Today, even a heavy storm risks inundating the slender Chignecto Isthmus, a 21km-wide (13-mile) land bridge at the edge of the Bay of Fundy that serves as a vital economic corridor, carrying about $27bn ($35bn Canadian) in trade annually (PDF). The Bay of Fundy already boasts the highest tides in the world, and with sea levels in this region set to rise by about a metre by 2100 – and possibly by more than double that under extreme scenarios – the risks facing this tiny strip of land have never been greater.

“This might be the most vulnerable spot in eastern Canada,” said David Kogon, mayor of the town of Amherst, Nova Scotia, which lies at the southern boundary of the isthmus. By 2100, sea level rise could potentially put up to a third of his town underwater and sever the only viable transport link between the province of one million people and the rest of the country.

“This province was born from the sea and is centred around our ocean frontage ... so the sea level rising is going to be an issue,” Kogon told Al Jazeera.

Across Nova Scotia, coastal communities are grappling with their exceptional vulnerability to climate change, as rising waters threaten to consume more and more land. With coastal erosion affecting many towns and cities, the provincial government in 2019 passed legislation to regulate what can and cannot be built on 13,000km (8,000 miles) of coastline, while local bylaws control how high above sea level new buildings must be constructed (PDF).

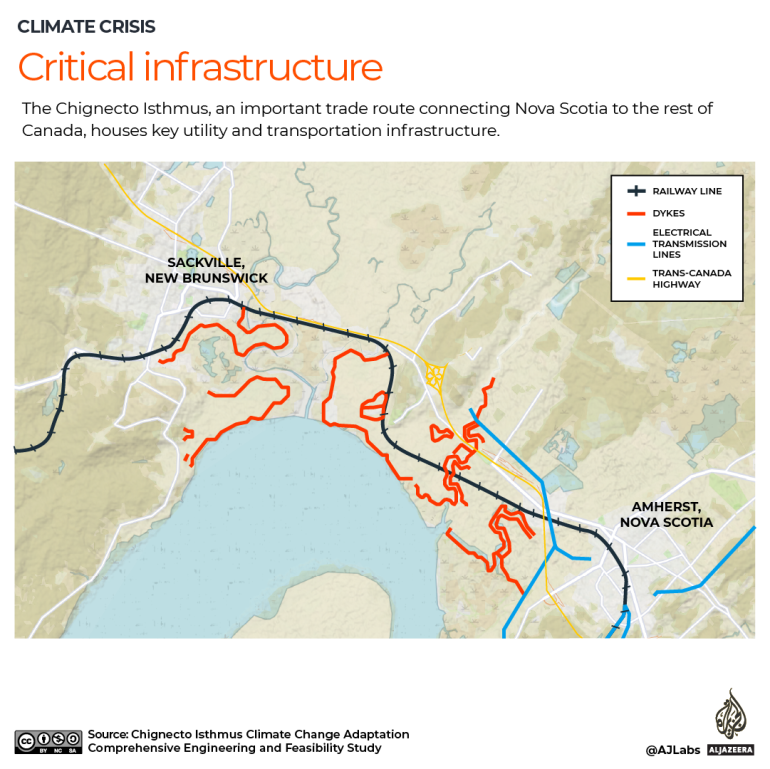

The Chignecto Isthmus, which connects Amherst to the New Brunswick town of Sackville to the north, is in a particularly precarious situation: Experts have long warned that unchecked sea level rise could one day fully submerge this strip of land, turning Nova Scotia into an island. While the isthmus itself is sparsely populated, a major flooding event could directly affect several thousand people in the two towns and have countrywide economic ramifications.

Protected by a system of earthen dykes originally built in the 1600s to facilitate the development of farmland, the isthmus houses critical utility and transportation infrastructure, including the CN Rail line and the Trans-Canada Highway. The Chignecto corridor is also the only route for wildlife, such as bobcats and endangered moose, to move in and out of Nova Scotia. A number of bird species that rely on these forested wetlands are at risk, while the isthmus “serves as a critical stopover site” for migratory waterfowl, according to the Nature Conservancy of Canada.