‘When he walked out of prison, Mandela set us all free’

Remembering the sense of hope and optimism in South Africa, 25 years after Nelson Mandela’s release.

Twenty five years ago today, Janey Halim was part of the ANC welcome committee gathered outside Victor Verster prison, waiting to greet Nelson Mandela as he emerged after 27 years in jail.

“It was a beautiful morning and we all just stood there with our eyes focused on the metal gate,” she recalled when I interviewed her in 2010.

Keep reading

list of 4 itemsSouth Africa seeks to stop auction of historic Nelson Mandela artefacts

A way of saying ‘we shall overcome’: Playing football on Robben Island

History Illustrated: Mandela – South Africa’s First Black Preside

After 4pm, more than an hour later than scheduled, a motorcade pulled up about 13.7m on the inside of the main prison gates and Mandela stepped out of a silver Toyota sedan with his former wife, Winnie Madikizela-Mandela.

“Then the gates opened and Nelson and Winnie walked towards us. Other people were cheering but I just cried and cried.”

Just over a week earlier, President FW de Klerk had taken South Africa and the world by surprise in announcing that his government had “taken a firm decision to release Mr Mandela unconditionally”. Only on February 10 was the date of his release disclosed, sparking frenzied speculation and anticipation.

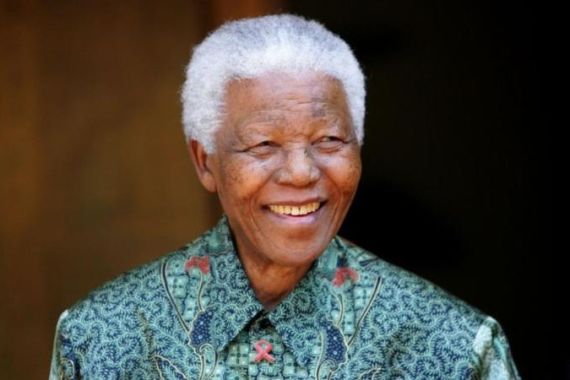

Picturing Mandela

It had been 24 years since the last photograph of Mandela had been published and few people knew what Mandela looked like let alone what kind of man he had become.

|

|

Many liberation activists feared that he might have gone soft or even sold out to the guileful National Party while much of the timorous minority white population, feared Mandela would be a vindictive and wrathful figure.

What emerged from Victor Verster prison that February afternoon was neither of these things. Instead, Mandela strode through the prison gates, statesman-like and dignified.

And his first speech as a free man offered some indication that he could be the one who might steer South Africa away from the brink of civil war and towards a peaceful, unified democracy.

Having walked through the prison gates, Mandela and Winnie got back into the ugly Toyota sedan and began the 64km drive to Cape Town. The plan was for them to drive to City Hall where a huge crowd had gathered outside for a hastily arranged rally.

But the throngs of jubilant supporters lining the route meant that Mandela’s progress was slow and as he approached downtown Cape Town his car was brought to a virtual standstill by supporters.

“People began knocking on the windows, and then on the boot and the bonnet,” Mandela wrote in his biography, Long Walk to Freedom.“Inside it sounded like a massive hailstorm. Then people began jumping on the car in their excitement. Others began to shake it and at that moment I began to worry. I felt as though the crowd might very well kill us with their love.”

Swamped by the people

American civil rights leader, Jesse Jackson, had a similar experience as his limousine arrived outside City Hall and was immediately swamped by people who thought it was Mandela.

Meanwhile some of the 100,000-strong crowd on Grand Parade in front of the City Hall were becoming restive and on the fringes there were clashes with the police. Some shops were looted and police fired birdshot killing one man and injuring dozens of others.

Olive Petersen was among the throng.

“It was a hot day and I had to stand for more than six hours with nothing to drink but the only thing I cared about was laying my eyes on Mandela,” she recalled in 2010.

When Mandela finally appeared on the balcony of City Hall the sun was dipping low. The crowd was signing and chanting but as Madiba took out his speech and borrowed Winnie’s glasses – his own having been left in prison – silence descended.

When Mandela finally appeared on the balcony of City Hall the sun was dipping low. The crowd was signing and chanting but as Madiba took out his speech and borrowed Winnie's glasses - his own having been left in prison - silence descended.

“Amandla!'” (“Power!”) he cried, his fist raised. “Amandla!” the crowd responded with one voice. He began by saluting all those who had made this moment possible – including combatants of Umkhonto we Sizwe, the armed wing of the ANC – before going on to make it clear then that the only way forward for South Africa would be elections.

“Our march to freedom is irreversible,” he said. “We must not allow fear to stand in our way. Universal suffrage on a common voters’ roll in a united democratic and non-racial South Africa is the only way to peace and racial harmony.”

His speech was carefully balanced stressing his commitment to peace and reconciliation with the white minority. “We call on our white compatriots to join us in the shaping of a new South Africa” he said. “The freedom movement is a political home for you too.”

Age and imprisonment

But while stressing the need for peace it was evident that age and imprisonment had not diminished this thin 71-year-old’s militancy. He called on the international community to continue to impose sanctions on South Africa and stressed the continuing importance of the ANC’s military capacity.

“The factors which necessitated armed struggle still exist today,” he told the jubilant crowd.

He finished his speech by quoting his words from his 1964 trial saying that they were as “true today as they were then”.

“I have fought against white domination, and I have fought against black domination. I have cherished the ideal of a democratic and free society in which all persons live together in harmony and with equal opportunities. It is an ideal which I hope to live for and to achieve. But if needs be, it is an ideal for which I am prepared to die.”

Mandela’s release heralded the start of a process that would eventually lead to a negotiated settlement and democratic elections in 1994. But it was also the start of a process of reconciliation and nation-building that is continuing to this day.

Speaking outside the prison gates through which Mandela had emerged on the 20th anniversary of his release, South Africa’s deputy president Cyril Ramaphosa told a small crowd “as Mandela walked through these gates … we were also being set free”.

But the significance of his release was felt far beyond South Africa’s borders. In a newly post-Cold War world that was undergoing a rapid and uncertain period of transformation, Mandela’s release gave a renewed sense of hope and optimism.

As Breyten Breytenbach, the Afrikaans dissident writer, wrote at the time: “Perhaps there is now a little more sense to our dark passage on Earth.”

Stefan Simanowitz worked for Nelson Mandela and the ANC from 1992 – 1994 helping to run the press office in the Western Cape.

The views expressed in this article are the author’s own and do not necessarily reflect Al Jazeera’s editorial policy.