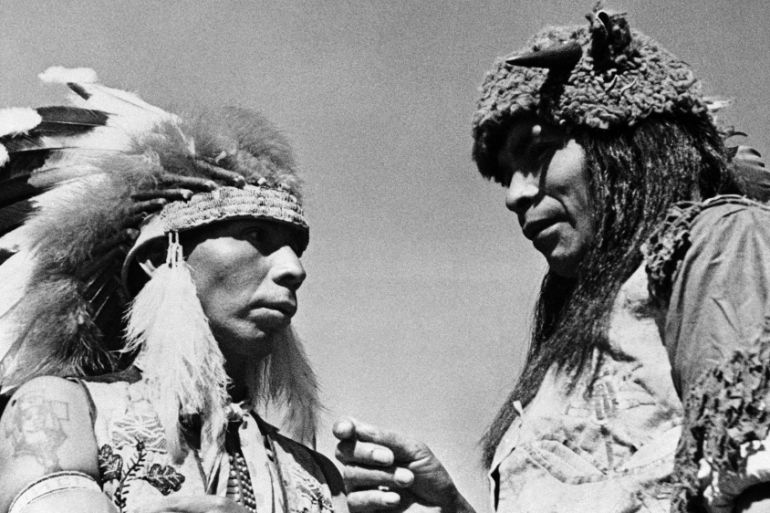

How Native Americans adopted slavery from white settlers

And how black people in Indian Territory were denied their rights even after their emancipation.

Last week marked the 153rd anniversary of the ratification of the 13th Amendment to the US Constitution in 1865. Rightly celebrated as a milestone for the black American community, the 13th Amendment led to the eventual liberation of all African Americans enslaved in the United States of the late 19th century. But the 13th Amendment did not free all black enslaved people in the boundaries of modern-day US.

Members of five Native American nations, the Cherokee, Chickasaw, Choctaw, Creek, and Seminole Nations (known as the Five Tribes), owned black slaves. Then located outside the territorial boundaries of the US in a region known as Indian Territory (modern-day Oklahoma), these sovereign nations were not affected by proclamations or constitutional amendments. Instead, separate treaties had to be made between the US and these Native American nations not only to free enslaved peoples, but also to formally end the American Civil War battles and antagonism between American and Native American troops.

Keep reading

list of 4 itemsThe Take: After Iran struck Israel, how did Jordan and Lebanon react?

The world cannot turn its back on Sudan and its neighbours any longer

Russia-Ukraine war: List of key events, day 784

The fact that by the time of the Civil War black chattel slavery had been an element of life among the Five Tribes for decades is rarely discussed. It is, however, an important aspect of US history which serves to remind us of the complexity of colonialism, exploitation and victimisation that laid the foundations of our country.

Captivity and slavery among Native Americans

The indigenous peoples of North America had utilised a form of captive-taking and involuntary labour long before European contact. But this form of bondage was neither trans-generational nor permanent. Captive-taking was most often used to replace a dead loved one within the family with a new person. The captive would then take on this deceased person’s sexual or labour-related capacities.

Through various avenues, such as “sexual relationships, adoption, hard work, military service, or escape, captives could enhance their status or even assume new identities.” After European contact in the 1500s, white Europeans persuaded Native Americans to enslave members of other Native American tribes using the European method of slave-trading, which focused on the accumulation of captives for sale and thus, profit, rather than for population augmentation.

The Native American slave trade thrived for over a century, but began to be largely phased out in the early to mid-18th century. An important factor in its decline was the Yamasee War of 1715-1717. After colonists in the English colony of Carolina began defaulting on some of their trade agreements and enslaving even members of their ally tribes, the Yamasee Nation began to question its own alliance with Carolina. Along with the Lower Creeks and the Savannahs, the Yamasees declared war on Carolina, killing 400 colonists, approximately seven percent of the white population. The Carolinian colonists put together a force of black slaves, militiamen, volunteers and friendly Native American nations, which defeated the Yamasees and their allies.

While the Yamasees lost, they succeeded in forcing European colonists to reconsider the risks inherent in the system of Native American enslavement. If Native Americans became angry at the terms of enslavement or allied Native Americans were accidentally enslaved, they might once again retaliate militarily. In addition, enslaved Native Americans often successfully escaped from their owners, as they were familiar with the geography and could elude slave catchers and return to their homelands.

Therefore, after the Yamasee War, the African transatlantic slave trade to the North American colonies drastically increased to account for the loss of Native American slaves.

Some members of the Five Tribes became owners of enslaved black women and men themselves, as they increasingly adapted to Euro-American norms, such as style of dress and governmental structure. Beginning in the late 1700s and intensifying in the early 1800s, members of the Five Tribes used enslaved black women and men as domestic and agricultural labourers. For example, Chickasaw planters exported an estimated 1,000 bales of cotton in 1830; this cotton was picked and processed by black slaves. Comparatively, in 1826, the state of Georgia produced 150,000 bales of cotton.

In 1860, about 30 years after their removal to Indian Territory from their respective homes in the Southeast, Cherokee Nation citizens owned 2,511 slaves (15 percent of their total population), Choctaw citizens owned 2,349 slaves (14 percent of their total population), and Creek citizens owned 1,532 slaves (10 percent of their total population). Chickasaw citizens owned 975 slaves, which amounted to 18 percent of their total population, a proportion equivalent to that of white slave owners in Tennessee, a former neighbour of the Chickasaw Nation and a large slaveholding state.

This made the Chickasaws the largest slave-holding nation of the Five Tribes, in proportion to their population. National laws restricted the movement of enslaved people, preventing them from learning to read and write, and prohibited interracial relationships.

However, as in the US, the majority of people in these nations did not own slaves. Large-scale crop production and the system of slavery that made it possible and lucrative were mainly adopted by wealthier Native families, whose prosperity allowed them to influence the political, social, and economic affairs of their nations. Thus, an influential proportion of tribal citizens stood to lose a vital part of their economic resources if emancipation took place.

The Five Tribes involved themselves in the Civil War militarily to preserve their practice of slavery and to fight for political autonomy. Members of all nations served on both the Union and Confederate sides of the war, and a number of battles took place within Indian Territory. After the war, the treaties signed between the US and all five of these slaveholding Native American nations, called the Treaties of 1866, ended wartime hostilities and freed and enfranchised people of African descent. These treaties were part of a larger American mission to take over Native American land, and also included land cessions and American settlement and railway construction in Indian Territory.

Citizenship rights

While the former slaves of the Cherokee, Creek, Seminole, and Choctaw Nations became tribal citizens due to the Treaties of 1866, throughout the 20th century, all of the Five Tribes eventually rescinded the tribal membership of these freedpeople and their descendants. Although their former slaves had lived among them for generations, sharing land, history, and trauma with them, the Five Tribes claimed that they were interlopers who had no place among them because they had no Native ancestry.

The descendants of these former slaves fought back, filing several lawsuits. On August 31, 2017, the descendants of people enslaved by members of the Cherokee Nation were victorious. The US District Court in Washington ruled that these descendants should have citizenship rights in the Cherokee Nation. Now the descendants of people enslaved by the Creek Nation have filed a similar suit, hoping to find commensurate validation.

So, when we observe and honour the anniversary of the 13th Amendment, let us remember that not all people of African descent had the same experience of freedom. Those African Americans living among western indigenous nations waited until the summer of 1866 to gain their freedom, and even then, they fought to find true liberation from economic, social, and political duress.

Just as our current moment sees white and black Americans arguing over the memory of the Civil War and the removal (or not) of Confederate monuments, so discussions of slavery in Native American nations and the historical relationships between the Five Tribes and people of African descent are also fraught with many difficult issues.

The story of the people of African descent owned by Native Americans is unique, but also simply another tale of coercion and community in the diverse African American experience.

The views expressed in this article are the author’s own and do not necessarily reflect Al Jazeera’s editorial stance.