Let’s bring the Caribbean struggle for reparations to Britain

European progressives should see CARICOM’s latest call for reparations as a call to action.

Britain has heard the call for reparations and ignored it for decades.

When the case for reparations is made, we are told to “move on” as then-British Prime Minister David Cameron put it to Jamaican politicians four years ago. When statues of imperialists and slaveowners come down, we are told that we are “trying to bowdlerise or edit our history” as Boris Johnson has recently said.

Keep reading

list of 4 items‘Crimes against humanity’ may have been committed in Sudan, says UN chief

The Take: How Iran’s attack on Israel unfolded

Europe pledges to boost aid to Sudan on unwelcome war anniversary

In other words, the conservatives insist we “move on” when the conversation of colonialism or slavery comes up, and when the statues that memorialise them come down, we are condemned for trying to “move on” from history. They cannot seem to make up their mind, but that should not be an obstacle to self-determination in its former (and some current) colonies. And that is what the case for reparations is about: self-determination.

On July 6, Caribbean Community (CARICOM) – an organisation of 15 countries in the Caribbean – renewed its calls for reparations, emphasising their importance for the second stage of independence in the Caribbean.

“We were not given a development compact,” Prime Minister Mia Mottley of Barbados argued, “we were given political independence.” According to her, the Caribbean has made great strides to reverse legal inequalities. But only reparations could help overcome the psychological, sociological, and economical inequalities that exist within Caribbean countries and between them and their former colonisers.

Here in Europe, progressives should understand that this is a call to action.

In his reflections on his friendship with Pan-Africanist George Padmore, the late Trinidadian scholar CLR James recalled that roughly 10 of his friends, mostly West Indian, were the ones that were agitating for the independence of Africa. They reared, trained and prepared young Africans to take the reign of government. They were all based in London, including several people who would become the first heads of states in their own independent countries.

“Most of the people,” he recalled, “looked upon us as well-meaning but politically illiterate West Indians.” The conversation for independence had not yet become mainstream, and some even said it would not happen for another 100 or so years. That was in 1935, only 20 years before the process would begin.

Now there are two reasons why this history is instructive. First, because the case for reparations, inspired by the works of thinkers like CLR James, Eric Williams, and Walter Rodney, is itself rooted in radical West Indian tradition that led to the agitation of African and Caribbean independence, and is indeed a continuation of that struggle.

Second, because that legacy of bringing the fight to London implied that the struggle could not be waged in the Caribbean and Africa alone. If the Caribbean right now is advancing the cause for reparations, then we need to bring that frame of thought and action back. People of African descent everywhere have to see this struggle through. There has never been a more opportune moment than the present, when we are fighting for the cause of Black lives.

At the University of Cambridge, there is a continuing inquiry into the legacies of slavery set to finish in 2022. In the best-case scenario, if all of the constitutive colleges get their act together and stop pedalling the simplistic lie that their only contribution to the slave trade was to train abolitionists, then the inquiry will follow the lead made by Glasgow University.

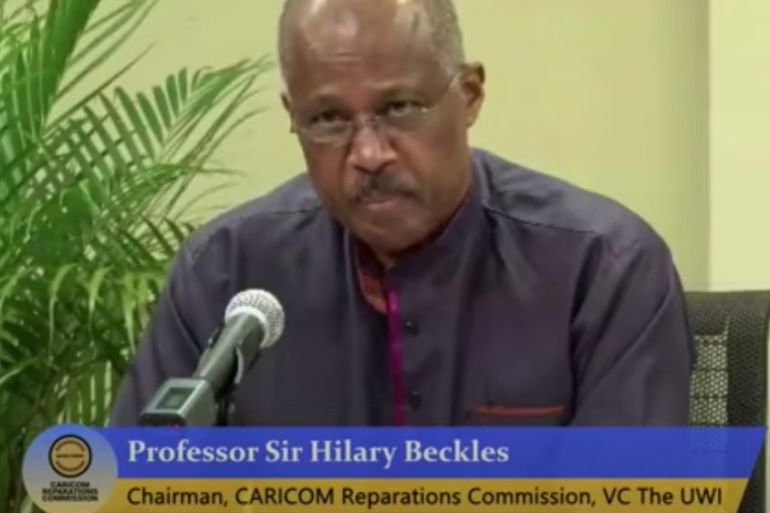

In 2019, Glasgow University publicly acknowledged its links to slavery and promised to raise and spend $26m in a “reparative justice programme”, which would include the establishment of a research centre to be shared with the University of the West Indies (UWI). UWI’s Vice Chancellor Hilary Beckles praised them for taking the bold step of saying “we are not going to research and run, we are going to research, and then we are going to stand up and repair”.

Students, staff and faculty at Cambridge should do what they can to ensure the inquiry does not entail the “research and run” approach and that it should, in fact, move in the direction of Glasgow. But educational partnerships, and other forms of aid, cannot be rebranded as reparations either. That is just a PR exercise. We are at risk here of stripping that word of its meaning.

Cambridge ought to deal with Beckles – not in his capacity as UWI vice chancellor but as the chairman of the CARICOM reparations commission. The student governments of each Cambridge college ought to demand that the inquiries in their colleges come with a promise of reparations and that those reparations be provided directly to the CARICOM Reparations Commission.

Now, this admittedly would require a shift in perspective among many students. The biography of Eric Williams, the first prime minister of Trinidad and Tobago, and the man whom Beckles credits with developing the case for reparations, is replete with his experiences of facing racism as a student in Britain. But like many of his peers, he focused less on making the university a hospitable space for Black students and prioritised self-determination in the British colonies.

The two, are of course, not mutually exclusive. Imagine if university students in Bristol, Liverpool and Glasgow, which Williams identified as the three cities that provid the link between early industrial capitalism and slavery, stood with the CARICOM reparations commission. What a force would that be?

Today, Black and minority ethnic (BME) politics cannot be merely about making sure we get more scholarships and hires for Black people in universities in Britain. This is important, but should not be our only goal. As the Caribbean announces its fight for its own Marshall Plan, we ought to return to an older pro-independence legacy here as well: In our universities, in our neighbourhoods and parliament, we should agitate in solidarity with the struggle for reparations.

The views expressed in this article are the author’s own and do not necessarily reflect Al Jazeera’s editorial stance.