Why the events in Jaffa of May 1, 1921 are important today

From May 1, 1921 to May 1, 2021, everything and nothing has changed between Israelis and Palestinians.

Officially, the war for Palestine, which ended with the establishment of the state of Israel and the exile of three-quarters of a million Palestinians, began on May 15, 1948, with the termination of the British Mandate, the declaration of Independence by Zionist leaders, and the formal start of hostilities between the fledgeling Jewish state and the country’s Palestinian population and Arab allies.

Others point to the United Nations Partition Resolution passed on November 29, 1947, and the war that commenced soon thereafter, as the actual beginning of the conflict. But an equally plausible argument can be made that the War for Palestine began more than a quarter-century earlier, on May Day, 1921 – not in Jerusalem but in a mixed neighbourhood along the sea between Jaffa and Tel Aviv.

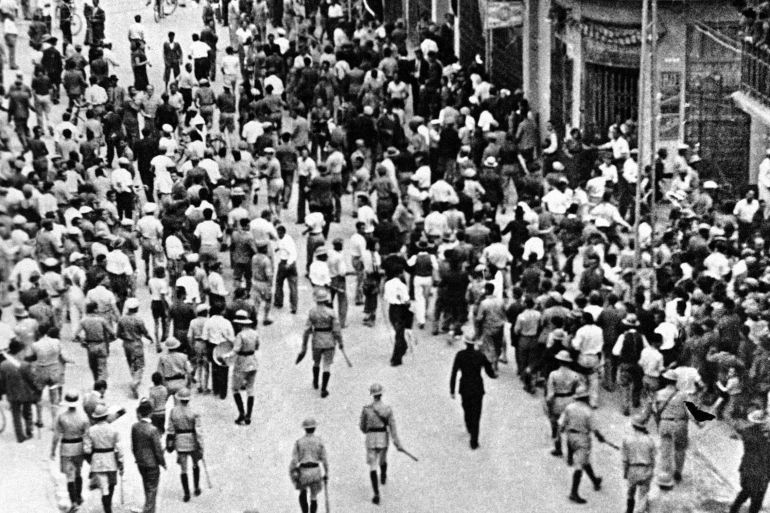

It was on that May 1 that a group of Jewish Marxists loudly marched into the Palestinian area of the neighbourhood of Manshiyyeh after clashing with more moderate Labor Zionists. With flags waving and chanting loudly for workers’ solidarity, their march was met by warning shots by the British gendarmes hoping to disperse them. Unfortunately, the Arab residents did not understand their slogans; and fearing the gunfire signalled a Jewish attack on the neighbourhood, they attacked first, starting a riot that quickly moved down into Jaffa and killed 47 Jews and 48 Palestinians. Hundreds more were made homeless.

The violence shocked the British occupation regime which was still getting its footing four years after conquering Palestine, but it should not have. By 1921, Jaffa’s rapid economic and demographic growth had made it the undisputed cultural and economic capital of Arab Palestine, where according to British police officials “you would get more information about political feeling than in any other part of Palestine”. At the same time, Tel Aviv, which since its creation in 1909 as the “first modern Jewish neighbourhood” in Palestine had gone from Jaffa’s “daughter” to a powerful competitor, the cultural and economic capital of Jewish Palestine.

Indeed, Tel Aviv’s encroachment on land belonging to Jaffa and the surrounding agricultural villages was already worrying enough for its last Ottoman governor, Hassan Bey, to build a mosque well north of Jaffa’s Old City in 1916 in an attempt to block Tel Aviv’s southward spread.

Jaffa’s Palestinian Arab population described the “storm” of violence in early May 1921 as a “revolt” or “revolution” (thawra, the same word used by protesters during the Arab Spring). For their part, Zionist officials admitted in their reports that it was a result of the “unnatural” expansion of the Jewish community, whose “seizing and spreading” over the rest of Jaffa and into the surrounding orchards was deemed a leading cause of the “mountainous” hatred between the two communities.

But rather than trying to mitigate the growing anger of the indigenous population, Zionist leaders pressed for unlimited immigration into Palestine, even as thousands of Jewish inhabitants of Jaffa migrated across the now official border to Tel Aviv, which was granted official recognition as a separate town 10 days after the eruption of violence.

In the next three decades, Jaffa and Tel Aviv would continue to clash, and occasionally cooperate, as the two cities and their respective national communities developed into full-fledged national rivals. The Palestinian “Great Revolt” of 1936 also began in Jaffa, while the Jewish bombardment of the city at the start of the 1948 war precipitated one of the largest exoduses of Palestinians into exile.

A century after May 1, 1921, the borderlands between Jaffa, now a relatively poor but endlessly gentrifying mixed neighbourhood of Tel Aviv, and the “modern” Jewish centre of the united municipality, remain a constant source of tension and even violence. Just as in Jerusalem and throughout the West Bank, secular and religious Jews alike take over Palestinian properties, push out the local population, and continue a self-described process of Judaisation (Yehudit in Hebrew, an official Israeli government term) that has occurred without rest now for 100 years.

Indeed, the dynamics of Jewish-Palestinian relations in Jaffa have always been a harbinger and microcosm of the broader Israeli-Palestinian conflict, putting the lie to long-made claims by Israel and its supporters of a firm difference in how Palestinians are treated on either side of the Green Line. In reality, most of the techniques deployed in the occupied territories after 1967 were first developed and perfected inside the sovereign 1948 borders of Israel.

In the mixed areas of cities like Jaffa, Haifa and Jerusalem, enough Palestinians remained so that their presence could not simply be erased and replaced by Jews and their number was “manageable” enough so that the demographic balance could be shifted with some effort.

Those who have paid attention to the constant struggle over territory, identity and political and economic power in Israel since 1948, and especially during the last five decades, have long understood that the territorially defined “two-state solution” championed by the Israeli “peace camp”, which was ostensibly at the heart of the Oslo “land for peace” formula, was doomed from the start. Israel had more than enough power and foreign support to retain permanent control over and continue to settle the occupied territories.

As the chances for peace became remote with the collapse of the Oslo process and the eruption of the Al-Aqsa Intifada in 2000, various groups of Palestinian, Israeli, and international scholars and policymakers came together to think about alternative methods of cohabitation on this deeply contested land. They developed or repurposed ideas ranging from a secular democratic state to various forms of federation, confederation and binationalism.

One of these suggestions was the idea of parallel states, first introduced in 2010 and detailed in our 2014 book One Land Two States: Israel and Palestine as Parallel States. The ideas outlined were the result of years of informal discussions between Israeli and Palestinian academics and experts, with the support of international colleagues.

The basic idea was to divide sovereignty rather than divide the land, and build a new kind of political architecture with two separate state structures both covering the whole territory, with freedom for people to move and to live in the whole area, thus preserving the notion of two separate states, while at the same time integrating the land into one geographic entity, with a common external border, and a common economic space.

Such a structure would enable Israel to satisfy its security imperatives through a continued presence in the West Bank while enabling Palestinians to return to all of historic Palestine, and both peoples to share Jerusalem as their capital. Crucially, wherever they lived, Israelis and Palestinians would remain citizens of their respective states, ending the “demographic threat” that for decades trumped promises of democracy on either side of the Green Line.

In 2012, a group of Israelis and Palestinians put forward a similar concept was under the rubric “Two States, One Homeland” (now known as “A land for all”), promoting a more traditional form of confederalism. Such initiatives have shown enough traction for the confederation to be a central theme at the just completed 2021 conference of J-street, the liberal Jewish counterpart of AIPAC.

With its century-long history of Palestinian-Jewish cohabitation – however forced and imbalanced – Jaffa could serve as a starting point for a shared and more equitable future. Instead, Jaffa continues to be treated more as a de facto Jewish settlement than a fully-fledged part of Tel Aviv, with land expropriation and militarised policing a continuous reality for its 20,000 Palestinian residents.

Looking back a century, Sami Abu Shehadeh, a lifelong Jaffan activist, Knesset member and chairman of the Balad Party, explained to us: “Of course 1921 happened in Jaffa; it was the centre of Zionist as well as Palestinian life, so we could see what was on the horizon by then. But even a century later, with Jaffa’s Palestinians only 1 percent of Tel Aviv’s population, there is barely an attempt to treat us as equal citizens. Because of that, the youth today continue to see themselves as part of the Palestinian nation, even if their ID card is Israeli.”

The 100th anniversary of the 1921 revolt reminds us how deeply rooted this conflict remains. But only a few years before the violence, Jewish and Palestinian leaders came together to help put street lights in Jaffa, formed an export society for the famed Jaffa Orange, and built a new boulevard in the heart of Jaffa to match the newly built, tree-lined Rothschild Boulevard in Tel Aviv. Cooperation and collaboration were possible then, and could be again – in Jaffa, Tel Aviv and across this sacred but deeply scarred land.

But only if it is based on the kind of equality, mutual respect and recognition that are at the heart of the various post-territorial solutions that are finally being given the attention they deserve. With a seemingly insurmountable imbalance of power in its favour, Israel has little incentive to acknowledge, never mind support, such efforts. But as the events of May Day 1921 remind us, conflicts that seem manageable today can fester for a century without a solution, rendering pyrrhic even the greatest of victories.

The views expressed in this article are the authors’ own and do not necessarily reflect Al Jazeera’s editorial stance.