How society’s indifference murdered a man in Paris

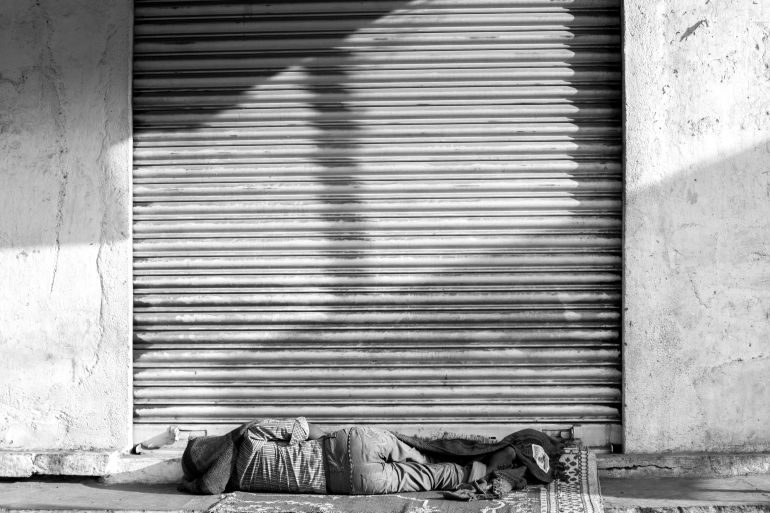

Swiss photographer René Robert froze to death on a busy street because he fell and, for nine tragic hours, he looked homeless – invisible, dangerous.

When I was 22, I flew to Berlin for a weekend. I sat in a café, drinking a surprisingly strong beer, watching the world stomp by. I noted an old man, hunched, unstable, hobbling slowly on the other side of the road. He fell. I watched the old man on the cold floor, from the warm comfort of the café, and considered crossing the road to help. But the streets were busy, so I thought by the time I reached the fallen man, someone would have emerged from the hubbub to help him back to his feet.

I watched four young men walk over him, a lady walk around him, and one family cross the road to avoid him. The old man had become invisible. I left the café, crossed the road and helped him to his feet. But as he stood up tall, the man pushed me away, angry to be helped. I sloped back across the road to the café, confused.

Keep reading

list of 4 itemsParis transport ‘will not be ready’ for 2024 Olympics: Mayor

‘My neighbours cleared rubble with their hands to rescue me’

Photos: The housing crisis for the poor in India’s capital

Some eight years later, at the age of 30, I was working in the city and living in Willesden Green, North London. I was a minimum-wage receptionist, dreaming of becoming an author. Writing between phone calls, burning the midnight oil with words and hope.

But my landlord raised my rent and, long story short, I quit my job to live in the local park and write my first novel. I’m still unsure if the decision was born out of depression, swirling circumstances, or the ridiculous belief that I was destined to be an author. Regardless, I packed my life into two bags, quit my job, and moved into the nearby Gladstone Park.

When I was homeless, just like that old man I tried to help in Berlin, I was invisible. My existence spread fear. People walked over me. They walked around me. They crossed the street to avoid me. It was as if I had taken a fall, and I was no longer a part of society.

Today, I’m about to finish my fourth novel. I’m a freelance journalist. From being single, skint and living under a tree, I’m now a married father of two and people pay me for my words.

But I still remember what it feels like to be invisible. Which is why Swiss photographer René Robert’s recent death in Paris hit me hard.

Eighty-four-year-old René died from hypothermia in the middle of a busy street after he fell and was ignored by passersby for more than nine hours. René Robert did have a home. But for those nine hours, he appeared homeless, so he was invisible.

The news of his tragic death made me think of my days at Gladstone Park. But most crucially, news stories about him made me remember that old man in Berlin. And I asked myself, if I was at a café in Paris, looking over to the street where René Robert fell, would I notice him? Would I now, having experienced homelessness and being invisible myself, do the same as I did 20 years ago and cross the road to help a stranger?

I fear the truth is, today, I wouldn’t have seen him fall at all. I would have been looking down at my phone, smiling at the 64th TikTok video on an infinite scroll. Indifferent to anything and everything, except me. Distracted by the possibility of a stranger pushing a heart emoticon on a comment, while confusing disconnection from the real world for actual attraction.

Today, in society, disconnection is rife. It is much worse than it was 20 years ago. Disconnection is an epidemic. And born from that disconnection comes a need for justification. In order to sustain disconnection, our minds fill the gaps in our knowledge with thoughts that explain our instinct for separation.

And this is never more evident than when those within society walk past, over, or around a homeless person. An everyday person will look up from their phone, see a homeless person, and immediately their thoughts will turn to whatever explains away – justifies – their indifference.

“He’s homeless so he must be a drunk.”

“She is on the street so she must have a drug problem.”

“I bet he’s not even homeless.”

“She must have done something wrong.”

Blame, blame, blame.

Society today, myself included, maintains an almost infinite capacity to commit deeds of horror while maintaining a narcissistic belief in its own wonderment. A successful society is a happy society, and so it has to be shaped from the clay of delusion. To function, it needs to believe that it is right and just and to have that belief, it needs to turn a blind eye to its own ugly reality. If today’s society were a person, he or she would be committed to a facility, for our own protection. And for the safety of our children.

But if indifference was the gun that fired at René Robert, then the bullet was fear. Fear allows us to turn our indifference to homelessness into a form of deluded self-protection. Society is afraid of itself, but especially afraid of what lurks beyond its control. Society fears strangers. Society fears the homeless. And so, like all fears, the homeless become invisible.

It was fear that led Parisians to step over René’s body. For nine tragic hours, René appeared to be homeless – someone invisible, someone who must have done something wrong, someone dangerous. That was his crime. And society punished him for it. For those nine hours, René was not only homeless, he was, tragically and simply, “less”.

Less than catching the bus, less than one more drink in the bar around the corner, less than the effort it would take to lean over, less than the time it would take to ask: “Est-ce que ça va?” less than arriving home five minutes later, less than all plans, less than a person.

He was already invisible to society because as soon as he hit the pavement, he looked like poverty wearing a pile of clothes. He fell as a member of society but landed as part of the homeless community. Society is a construct that has evolved over years to protect those who live within one, from the fears of being on the outside of one. In that regard, Robert was dead before he hit the ground.

Blindness is compliance. Silence is permission. Indifference is society.

In the end, it wasn’t a person with a house, a job, or a family who reached down to offer help to René. It wasn’t a fortunate member of our club of wonders we call society. The hand that reached down to touch René, to ask if he was okay, was the hand of a homeless man. A man with no possessions was the only human who possessed the compassion and absence of indifference, to call emergency services.

And when later found, this man didn’t want to give his name. Because, unlike those inside society, the one thing a homeless person owns is their name. Why should he offer his name to a society so indifferent that the people who live within that abundant society couldn’t spare a moment to check on one of their own?

It was Gandhi who said poverty is the worst form of violence. Yet here we are, in 2022, with the richest people on the planet growing richer and being praised for their success while the poor are poorer than ever and, to put the boot in, are blamed and vilified for being there. Gandhi died in 1948, but perhaps if he were still alive today, he would say the worst form of violence is stepping over a person to leave them to die from hypothermia on the cold streets of Paris.

Because indifference can be ignorance, it can be judgement, self-protection or even disdain. But to René Robert, on the night of January 18, our collective indifference was exposed for what it’s always been – an act of violence.

The views expressed in this article are the author’s own and do not necessarily reflect Al Jazeera’s editorial stance.