Women in science should be the norm, not the exception

This International Women’s Day, let’s start working towards ending gender discrimination in science for good.

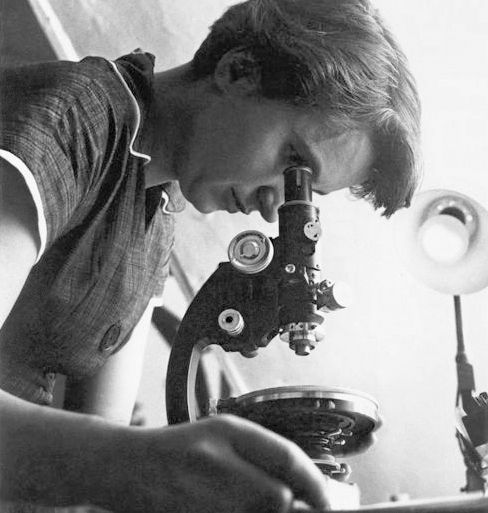

Every day, scientists across the world labour to come up with ever more accurate and inclusive answers to humanity’s most fundamental queries about the natural and social world. Using earthbound tools in tandem with their intellects and imaginations, they not only answer crucial questions like “What is the basis of life” and “What is the foundation of matter?”, but also try to provide practical solutions to our everyday problems.

In this context, it is easy to assume that in the world of science, where the pursuit of knowledge should take primacy over all else, oppressive social constructs and biases that hinder almost all other aspects of our lives are not as influential – it is easy to assume scientists can unite on common ground as they explore existential questions. The sad reality, however, is that women scientists have been forced to fight first for a seat at the table, and then for recognition, since the very beginning.

Keep reading

list of 4 itemsHong Kong’s first monkey virus case – what do we know about the B virus?

Why will low birthrate in Europe trigger ‘Staggering social change’?

The Max Planck Society must end its unconditional support for Israel

One of the most obvious, and depressing, examples of gender discrimination in science is perhaps the erasure of English chemist Rosalind Franklin’s crucial contribution to the discovery of the double-helix structure of DNA.

“Our dark lady is leaving us next week.” On March 7, 1953, Maurice Wilkins of King’s College, London, wrote to Francis Crick at the Cavendish laboratories in Cambridge to announce his “obstructive” female colleague Franklin’s planned departure from King’s.

Wilkins appeared to be under the impression that with the “dark lady” gone, he, Crick and their colleague James Watson would be free to go ahead and quickly decipher the code of DNA. And they seemingly did. One month later, Crick and Watson published a groundbreaking article in Nature magazine on the structure of the DNA molecule. They were immediately celebrated for their discoveries, but they seemed to “forget” to mention that the work of Franklin, their “dark lady”, was absolutely crucial to their discovery. The then 32-year-old woman had carried out a series of experiments that provided the visual template to prove the now-famous double helix is the blueprint for our biology.

Rosalind Franklin was born to a liberal Jewish family in London. She was driven to study science because of her natural curiosity. Eventually, thanks to hard work and ambition, she was able to transform her fascination with the physical world into a successful career in science despite many obstacles she faced, merely for being a Jewish woman in a man’s world.

It was the principal investigators at the King’s laboratory – all men – who made the calls, secured funding and stood to gain from any discoveries made there. But it was Franklin who did the labour and laid the ground for the discovery of the double helix. Sadly, she was never credited for or gained from her groundbreaking discovery in her lifetime. She died of cancer in 1958, at the young age of 37.

In 1962, Franklin’s former boss Maurice Wilkins, Francis Crick and James Watson were awarded the Nobel Prize in Medicine/Physiology for discovering the molecular structure of DNA – a discovery they were only able to do because of Franklin’s hard work. Franklin was not nominated for the Nobel Prize alongside her male colleagues for seemingly technical reasons: the rules at the time put limits on how many people could share the award and nominees had to be alive at the time they were nominated. Nonetheless, none of the three scientists who earned this highest recognition in science felt the need to let the world know how crucial the woman they once mocked as “dark lady” was to this discovery. Indeed, Franklin’s contribution to the discovery of DNA’s molecular structure was not publicised until years later.

Some may claim the erasure of Franklin’s work and achievements during her lifetime was not a result of systemic discrimination, but an anomaly – something born of bad luck, a reflection of her colleagues’ pettiness or her own inability to publicise her success.

Many point to the perhaps only well-known female success story in science from the 20th century to claim that women in fact had the opportunity to be part of the scientific world and gain recognition for their discoveries since the last century.

Sure, Marie Curie did win her first Nobel Prize, for physics, seventeen years before Franklin’s birth, in 1903. Not only that, she won a second Nobel Prize, this time in chemistry, eight years later in 1911. And it is true that Curie was widely recognised for her work during her lifetime. But Curie’s extraordinary work and achievements cannot and should not be used to conceal the fact that women have long been sidelined, ignored and erased in science. It is Curie who was the anomaly (and who was married to an established male scientist who likely helped her gain recognition in the undeniably male-dominated world of science in the early 20th century).

For every Curie, and there are not that many, the history of science is full of dozens of Franklins. And perhaps thousands of other women who had so much to contribute to science but were not even allowed into the laboratory.

The world of science is still dominated by men 22 years into the 21st century. This is not because, as some claim, women and non-binary people are bad at or not interested in science, but because they are fighting against sexist ideology and policies that are deeply entrenched in academic institutions.

It was only in 2005 that economist Lawrence Summers, then president of Harvard University, publicly claimed that the underrepresentation of women in the sciences is not due to discrimination, but rather, “biological differences” between men and women. His statement provoked a furore and was widely condemned by feminists at Harvard and beyond. Nevertheless, nearly two decades later, his views based on nineteenth-century essentialist notions about gender and biology are still held – overtly and covertly – by people in positions of power in academia.

Even though women have made huge gains towards increasing their representation in science in recent years, they are still significantly underrepresented. According to research by UNESCO, today, globally, only 33.3 percent of all researchers are women, with rates varying depending on the country. Furthermore, female researchers tend to have shorter, less well-paid careers. Their work is underrepresented in high-profile journals, and they are often passed over for promotion.

To achieve true gender equality, it is crucial to acknowledge and address the underrepresentation of women in science, and the additional obstacles women scientists face because of their gender. Moreover, addressing gender disparity in science would help us better address gender-based discrimination in many other areas, especially health.

Indeed, today many diseases that disproportionately affect women are under-researched.

For example, take fibroids, a life-limiting, painful disease that impacts approximately 26 million people with wombs in the US. Black women are two to three times more likely to have the disease. Despite the disease being so widespread, very little is known about it. Women suffer in silence for years before receiving a diagnosis. If there were more female researchers, especially Black female researchers, and they had the same level of access to grants as their white, male colleagues, we perhaps would have known more about, or even have an easy, affordable cure for, fibroids by now.

It needs to be acknowledged that people and organisations all over the world are working to end gender inequality in science. Several regional institutions in sub-Saharan Africa, for example, have taken steps to promote women’s participation in science. Since the late 1990s, the Southern Africa Development Community have been allocating resources to ensure girls and boys have equal access to science and mathematics education. The East African Community and Economic Community of West African states have similarly taken steps to encourage women’s participation in science. In 2010, the African Union established the Kwame Nkrumah Regional Award for Women Scientists – named after Ghana’s first president – and has been providing cash rewards to its recipients ever since.

Similar programmes, funds and awards have been established in other regions, from America to Asia and Europe, to increase women and girls’ participation in science and remove barriers from the paths of female scientists.

But these initiatives can only help narrow the gender gap in sciences if they can go beyond paying lip service to calls for equality and justice in the world’s classrooms, labs, universities and other scientific institutions.

Women can only take their rightful place in the world of science if societies start perceiving and addressing gender disparity in this arena as part of a wider labour struggle. We can only fully end gender inequality in science by building egalitarian, just workplaces for scientists that are free from harassment of all kinds as well as exploitative wages. Like in all other areas of work, unionisation can help make the world of science more just.

As Zachary Eldredge and Colleen Baublitz noted in Science for the People, labour unions can not only help defeat sexism in science-related work environments, but can also “offer a fundamental rebalancing of power, support for targets of harassment, and greater transparency and accountability.”

To end gender inequality in science, beyond making structural reforms in universities and other research facilities and introducing policies that target gender discrimination in education, we also need to rethink how we perceive science and scientists.

Today, there is still a belief that there is a single genius – or a very small team of geniuses – behind every groundbreaking scientific discovery or invention. And, as most societies are still more inclined to give men credit for a major achievement and put already established men on a pedestal, this results in “star” male scientists gaining fame and being cherished, while the teams that make major scientific breakthroughs possible, teams that include many women, end up being sidelined.

In other words, what has happened to Rosalind Franklin half a century ago, is still happening today, to countless women. In 1968, in the epilogue of his book, The Double Helix, James Watson wrote, “Since my initial impressions of [Franklin], both scientific and personal (as recorded in the early pages of this book), were often wrong, I want to say something about her achievements.” He then goes on to describe her extraordinary work and abilities, and, the enormous barriers she faced as a woman in the world of science. Reading this reflection, this postmortem admission of the magnitude of Franklin’s abilities and achievements, I could not help but feel angry. Angry that she never got to hear these words of praise from Watson when she was alive, angry that she had never even been considered for a Nobel Prize, angry that we would never know what she could have achieved if she was not sidelined, ridiculed and wronged just because she was a woman in a male-dominated field.

But even more so, what incensed me was the realisation that there are likely millions of Rosalind Franklin’s today, who are trying to do science and get the world to recognise their achievements – millions of women being deemed the “dark lady” by the likes of Watson, Wilkins and Crick.

On this International Women’s Day, let’s remember exceptional women in science like Rosalind Franklin. And let’s start working towards building a world where women in science are not an exception, but the norm.

The views expressed in this article are the author’s own and do not necessarily reflect Al Jazeera’s editorial stance.