It is not true that Pelé did not fight racism

Throughout his life, the Brazilian football star stood up to oppression, inspiring Black people at home and abroad.

In the days after the death of football star Pelé, there was a global outpouring of grief and much reflection on his legacy. I, like millions of other fans across the world, was mourning. Although I had never met Pelé in person, it felt like I had lost an elder, who I was close to and deeply admired.

There was a lot of international media attention, a lot of obituaries, articles, interviews, reports acknowledging his iconic status and his sporting achievements. But there was one persistent line of commentary that irked me.

Keep reading

list of 4 itemsSaudi reviews football fan rules after whip attack

Bayer Leverkusen win first Bundesliga title, ending Bayern Munich’s reign

Arsenal shocked by late Aston Villa double as title tilts towards Man City

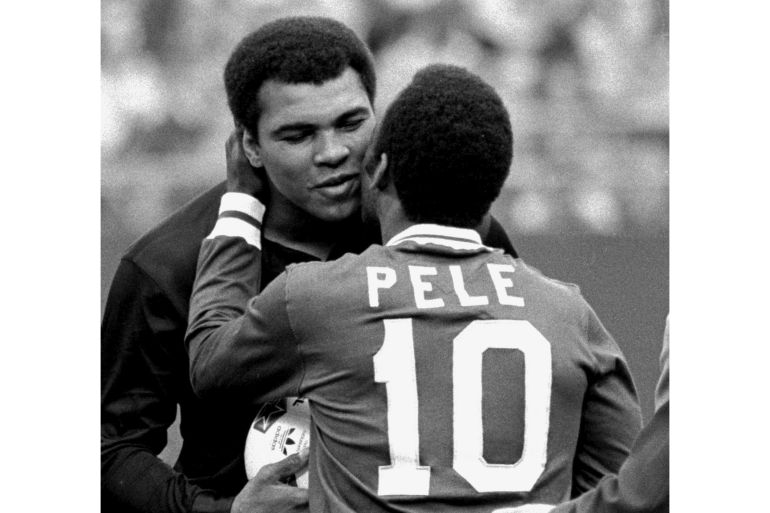

Sports observers and media outlets kept insisting that Pelé did not speak out against racism. Some would mention it in passing, others would dedicate whole segments to it, still others would bring up the inevitable comparison with American boxing star Muhammad Ali. This criticism was often levelled at Pelé while he was still alive, and he was not spared even in his death.

As an Afro-Brazilian, I feel this persistent scrutiny of what Pelé said or did not say is unfair, to say the least. The fact that he did not make certain statements does not mean he did not participate in the fight against racism.

Throughout his life and career, Pelé experienced racism and discrimination. He was keenly aware of racial inequalities and injustices, and he confronted them in a different way than some other Black sports stars who were his contemporaries.

Pelé was born just 52 years after Brazil abolished slavery in 1888, the last country in the Western hemisphere to do so. But growing up, he faced neither apartheid nor Jim Crow laws. Brazil at that time had made racism illegal and considered itself a “racial democracy”.

The idea that the country enjoyed racial harmony was put forward in the 1930s by Brazilian sociologist Gilberto Freyre. Himself a white wealthy man and a descendant of European colonisers, he claimed that Portuguese colonisation was somehow benign and that slavery was not as gruesome as in the United States and therefore, Brazil did not suffer from the same type of brutal structural racism.

This idea – or rather myth – was quite durable and even I was taught at school and university many decades later that Brazil somehow had exceptionally positive relations between the races thanks to supposed high rates of miscegenation.

That, of course, was and still is not the case. Brazil of the 1940s and 50s, when Pelé was growing up, was heavily racially divided. The elites were almost exclusively white, while the majority of the poor were Black, Indigenous, and mixed-race. Meanwhile, the government continued to encourage European immigration in order to boost the number of (the more “desirable”) whites in the country.

Brazilian football also suffered from racism. The sport had been brought into Brazil at the turn of the century by wealthy white men – like Oscar Cox and Charles Miller – who had studied in Europe. In the early days of Brazilian football, there were attempts to forbid Black people from playing in official matches and later, in the 1910s and 20s, some Afro-Brazilian players felt compelled to straighten their hair and put rice powder on their skin to hide their African features.

Despite this reality, the myth of “racial democracy” persisted and ended up weakening anti-racist activism. Although at that time, Brazil had a Black emancipation movement, it was not as strong as the civil rights movement in the US or the anti-apartheid struggle in South Africa.

The idea of “racial democracy” also instilled a culture of denial – that racism did not exist. This was reinforced by the media and the military dictatorship which came to power in Brazil in a 1964 coup.

Pelé was aware of these dynamics. He was playing a sport dominated by whites, faced media controlled by whites and a merciless dictatorship run by whites; he knew that being confrontational would not take him far. In fact, speaking out against those in power resulted in torture and death at that time.

As Brazilian historian Ynaê Lopes dos Santos has pointed out: “This stance that he took was very calculated, coming from a Black man who knew how to play the game of racism in Brazil. In this sense and many others, he is a winner. A Black man that became a Brazilian symbol, a country that in many moments projected itself as white. This is based on a very sophisticated assessment that he made on how Brazil works.”

Throughout his career, Pelé persistently experienced racism. He had a number of racist nicknames that football fans and the media would use and often heard monkey chants during matches.

But as he said in 2014 – in response to questions about racism in Brazilian football: “If I had to stop or shout every time I was racially abused since I started to play in Latin America, here in Brazil, in its interior, every game would have had to be stopped.”

And not being vocal did not mean he was not fighting or resisting. When he decided to end his career in the national team in 1971, he was punished for it, with two events meant to celebrate his successful career cancelled. When the Brazilian authorities tried to force him to come back and compete in the 1974 World Cup, he refused, despite the persistent pressure and threats.

So, Pelé fought racism and oppression through achievement, opening the door for other Black boys and girls to follow and inspiring Black Brazilians to dream big and defy discrimination.

It is not an easy choice to stay silent when you are racially abused. I know that all too well.

When I was in journalism school, a few professors picked me for an internship programme. They kept calling me “our project” as if I was a test subject and the reason they had picked me was to show that in our elite school, even young Black people could make it.

Later as an intern at a São Paulo public TV station, I had to endure in silence a supervisor making racist jokes, an anchor telling me that without my braids I looked like a “real human being” and a producer making monkey noises on my last day there.

I knew that if I had openly confronted all these racist individuals, my career would be jeopardised and the efforts of my family to support my education would be wasted.

Later in life, I would also be criticised for not being more vocal by white liberals who never experienced racism. But I knew that their demands for me to take a more activist position were really a way to weaponise my pain and tokenise me.

Still, my experiences of racism are probably just a fraction of what Pelé had to overcome in his life and career.

The fact that he did served as a major inspiration for my grandparents’ generation. His achievements also transcended the field of sports. After he retired from football, he became a successful businessman, acted in a Hollywood movie, was appointed a UNESCO goodwill ambassador, took the post of a minister of sport and was even knighted by British Queen Elizabeth II.

He demonstrated that anything was possible for a Black Brazilian man and that is why people called him “Rei Pelé” – King Pelé. I remember how when my grandparents would talk about him, the tone of their voices would change as if they were talking about their royalty, their Black king.

By the time I was growing up in the late 1980s and early 90s, more Black people had made it to positions of prominence, including people in my extended family. But racism, of course, persisted. Afro-Brazilians were still a rare sight in Brazilian media, most often appearing in slavery-themed soap operas or as minor characters, often mocked, in TV shows. So I would regularly switch to American shows and films, where Black actors like Philip Michael Thomas and Danny Glover had become my idols.

Pelé, nevertheless, remained a permanent fixture on Brazilian TV. He was one of the few Afro-Brazilians that I saw being respected when appearing or being mentioned. He motivated me to fight for my place in the media, a sphere which continues to be heavily dominated by white people.

Now after his death, the global mourning has made me realise how much Pelé also meant to other Black people across the world. “Africa has lost a great son,” Ivory Coast Consul Tibe bi Gole Blaise said while attending Pelé’s wake at Santos stadium.

Thus, I think the criticism thrown at Pelé and comparisons between him and Muhammad Ali are unfair. They degrade his contribution to the anti-racism struggle in Brazil and the world while presenting him as someone who neglected his race.

That is really not the case. Pelé fought racism and carried the weight of the struggle so the generations of Black people that came after him would find more doors open. His way of fighting racism should be respected, just as Muhammad Ali’s has been.

I am grateful to Pelé for what he did: donning the Brazilian football jersey and leading Brazil to the status of world power in football, breaking the glass ceiling, ripping the whitewashed image of Brazilian identity and paving the way for Afro-Brazilians to claim equality and respect in Brazilian sport and society at large. He truly played his “beautiful game” on and off the pitch.

The views expressed in this article are the author’s own and do not necessarily reflect Al Jazeera’s editorial stance.