How Formula 1 is stepping out on the world stage

What the growing popularity of motor sport says about the world we live in.

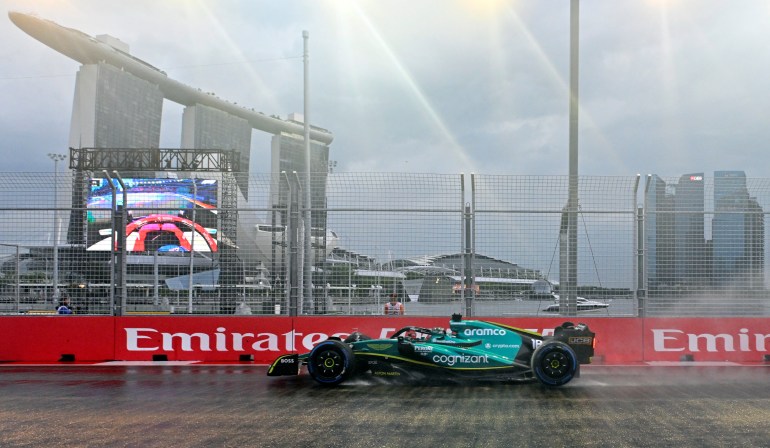

Formula 1 is having a moment, and it’s attracting a new generation of fans to the speed, danger, and lifestyles of its rich and famous drivers. More countries now want the status that a Formula 1 race brings, too. After this weekend’s Grand Prix in Japan, drivers will set off to the US, Mexico, and Brazil before the final race of the season in Abu Dhabi. In this episode, we look at how a sport that was considered esoteric, elitist, and European is going global.

Keep reading

list of 4 itemsThe Russians fleeing Putin’s military draft

After months of violence, Brazil chooses their new leader

Women, life, freedom: The chants of Iran’s protests

In this episode:

- Simon Chadwick (@Prof_Chadwick), professor of sport and the geopolitical economy at SKEMA Business School

Connect with us:

@AJEPodcasts on Twitter, Instagram, and Facebook

Full episode transcript:

This transcript was created using AI. It’s been reviewed by humans, but it might contain errors. Please let us know if you have any corrections or questions, our email is TheTake@aljazeera.net.

Kevin Hirten: Formula 1 is having a moment.

[SOUND OF CARS]

Kevin Hirten: And it’s attracting a new generation of fans, drawn to the speed..

Newsreel: And it’s pushing over 340km/h (211mph).

Kevin Hirten: … the danger …

Newsreel: That is a red flag and you can see the damage that’s been done there.

Kevin Hirten: … and the lifestyles of its rich and famous drivers. And a sport that was once considered esoteric, elitist and European is stepping out on the world stage. I’m Kevin Hirten, in for Malika Bilal. And this is The Take.

[THEME MUSIC PLAYING[

[MUSIC PLAYING]

Kevin Hirten: Today, I’m talking with Simon Chadwick. He’s a professor of sport and geopolitical economy at Skema Business School in Paris. And this is what he associates with Formula 1.

Simon Chadwick: Historically, fast cars, white men, tobacco, gorgeous women. Nowadays, technologically advanced, commercially developed, digitally savvy.

Kevin Hirten: Simon’s also been an on-again and off-again fan of Formula 1 since the 1970s, when his dad got him into the sport. Things were a bit different back then. Cigarette logos were plastered all over the race cars, and models were paid to come to the racetrack to promote their products. The audience was different, too.

Simon Chadwick: As a British guy, whose, if you like, formative Formula 1 years were spent in Britain, the typical audience tended to be middle-class, middle-aged white guys and some kids. And at that time, I was one of the kids. The former head of Formula 1, Bernie Ecclestone, once referred to the typical F1 audience consisting of men who buy Rolexes. And for a long time, I think that’s how it was. This was not a cheap sport. You actually needed a car, which is very expensive, and you need to be able to get to the circuit and lots of other circuits to be able to race. And so unlike, for example, football – you take a ball and you kick in the street and that’s it – with motor sport, it was very, very different. So there were barriers to entry in terms of consumption. So when I look at the new audiences now, I’m actually quite amazed because these audiences are number one, bigger, number two, much more diverse, and I guess number three, crucially, actually consuming the sport in a different way.

[MUSIC PLAYING]

Kevin Hirten: I’m one of those new F1 fans. And by the time I started watching, a change was already in full swing.

Simon Chadwick: Historically, really historically, Formula 1 is just a bunch of club racers, people who like racing cars, driving cars incredibly quickly. And so for a long period of time, the principles of amateurism really were pervasive within Formula 1.

Newsreel: Jack Rabham in a car of his own make and Graham Hill in a BRM while reigning champion Jim Clark was driving a Lotus. All the top names in the Austrian Grand Prix.

Simon Chadwick: Then we saw a man called Bernie Ecclestone become prominent.

[CAR SOUND]

Simon Chadwick: Bernie Ecclestone was a used car dealer. He was also a club racer. He then became a team owner. He was very politically astute and he navigated himself into a position whereby essentially he owned and controlled and was the face of Formula 1. He was financially savvy. He knew how to make money, but there was a long period of time, I think, when many observers felt that Formula 1 was really punching below its weight, certainly in financial and commercial terms. And it was only then really with the sale of Formula 1 by Ecclestone, in 2016, that things really began to change.

Kevin Hirten: That’s when Liberty Media, an American company, bought Formula 1 for $4.4bn.

[MUSIC PLAYING]

Kevin Hirten: Some of the cultural changes had been making their way into the sport for a while. Formula 1 had already banned cigarette advertising in the mid 2000s. And Liberty also formally got rid of grid girls – the women models involved in the sport’s opening ceremonies.

Newsreel: For decades, the Formula 1 grid girls have been part of the Grand Prix lineup displaying the driver’s numbers. But now the sports bosses have decided it’s time for the girls to go.

Kevin Hirten: And then, there were the business changes.

Simon Chadwick: The operating model, I think, of Formula 1 has become more strategically commercial, but also more globally commercial. Arguably, the pandemic was also significant, too.

Kevin Hirten: Shutdowns from the pandemic upended the sports world.

Newsreel: More of the world’s biggest sporting contests cancelled or postponed.

Newsreel: The European championships this summer will be postponed until 2021.

Newsreel: The 2020 Olympics in Japan will be postponed.

Kevin Hirten: This hit Formula 1, too, of course. Drivers and their teams went to Australia in March of 2020 for the first Grand Prix of the season, which was cancelled just before practice sessions for the race were set to begin. But some drivers went through with the race, just virtually.

Driver: This feels like the actual thing. I feel like I’m in Australia right now.

Simon Chadwick: Formula 1 drivers were, instead of attending Grand Prixs because of COVID, they were, they were racing fans online as part of kind of console games. And then we all started binge watching Netflix.

Kevin Hirten: Simon’s talking about Drive to Survive. That’s the Netflix show that converted me from a casual fan to a never miss a Grand Prix fan. It completely transformed the image of a sport that on TV broadcasts can seem repetitive or overly technical.

[MUSIC PLAYING]

Kevin Hirten: Suddenly, Formula 1 isn’t just 20 strangers driving around a track for two hours. Now, I have drivers I love and teams I hate. I’m invested.

Drive to Survive trailer: These guys have an almost fight a pilot mentality, and that’s what separates them from mere mortals.

[MUSIC PLAYING]

Kevin: I think F1 is intimidating for people who don’t understand it, it’s like getting into jazz or something. So this comes along and it takes, you know, a few nights of binge-watching and suddenly you’re up to speed on the rules. But I think most importantly what it does is it accentuates the glamour, the drivers, the lifestyle. There’s all these other things going on beneath the surface. And that show really plays that up.

Simon Chadwick: I think I get what you say about jazz. And I like using jazz as a metaphor very often. So it never occurred to me before that Formula 1 used to be John Coltrane and perhaps it’s Kenny G now, or you know maybe, maybe someone of that nature. But you’re right there has been this transformation. What I think is significant about Netflix apart from that pandemic period binge-watching is the way in which. it helps to recapture what sport is all about, which is that uncertainty of outcome.

Kevin Hirten: You also get a sense of what these drivers go through day in and day out, how difficult and dangerous it is to drive what is essentially a jet with wheels.

Simon Chadwick: There is a skill set required to be successful in Formula 1 that most people don’t realise and understand. It’s physical strength, it’s mental strength, but it’s also about the ability to make decisions very, very quickly.

[MUSIC PLAYING]

Simon Chadwick: A while back, I did a webinar with Mika Hakkinen, who was a Formula 1 world champion. And he was saying, well, he’d be driving along a straight at 300 kilometres (186 miles) in an hour…

[CAR SOUNDS]

Simon Chadwick: … and you blink. And literally, by the time you’ve opened your eyes again, after the blink you’re there on the corner and having to make a decision.

[MUSIC PLAYING]

Simon Chadwick: Your rival is coming up on the inside and if you touch one another, you know, there’s a chance that one of you could actually be seriously injured. And the way he told this story, I just thought, “Wow, you have to be incredibly sharp, your reflexes have really gotta be incredibly well honed.” So, you know, I think Formula 1 drivers are a special breed.

Kevin Hirten: But skillful driving does not a Netflix series make. What made it a hit is the human drama around the paddock:

[MUSIC PLAYING]

Kevin Hirten: High stakes, hot tempers and seething rivalry – all the elements of good reality TV.

Simon Chadwick: I think the Netflixisation of Formula 1 is switching on people to not just these incredibly well-designed, expensive pieces of equipment that go very, very quickly, but it’s also introducing them to these real people who sit inside these cars and their stories. And obviously those stories are not just off the track. They’re also on the track as well.

Kevin Hirten: Don’t get me wrong, drivers beefing with each other has always been a big part of the sport, but Simon says it used to be in the background. Now, it’s front and centre.

Simon Chadwick: I recall an incident back in the 1980s, when a Brazilian Formula 1 driver Nelson Piquet…

Newsreel: And out comes Piquet, my goodness.

Simon Chadwick: Piquet was involved in a crash with an on-track rival and, as both of them got out of their cars, the first thing that Piquet did was to attack, physically attack his rival.

Newsreel: Ah, take that, and oh my goodness, well, Nelson Piquet understandably livid with rage.

Simon Chadwick: Now, back in the day, it was kind of, you know, how dare he do that? You know, there are certain standards of behaviour that you must uphold in this sport. Whereas now I think in terms of Netflix, wow, that’d be gold dust. Can you imagine? Yes, sport is about the drama, the tension, the excitement. But by the same token, I know there are people out there in the world who do see this now essentially transforming Formula 1into a staged experience.

[MUSIC PLAYING]

Kevin Hirten: There’s so much going on because you have a sport that is transforming itself. I mean, now when I open up Twitter during a race, I mean, even like people’s mothers are tweeting about, you know, Danny Ricardo’s tire strategy. I mean, everybody is talking about Formula 1 right now and it kind of feels like the sport of the future.

Simon Chadwick: It’s really interesting that you put it – the sport of the future, because I think in my mind, I’ve still got a very kind of old fashioned, almost parochial view of Formula 1. But I do realise that there is this newer, shinier, more relevant, more engaging Formula 1. You’ve mentioned their social media. When I was a kid back in 1970s, the way in which I typically watched Formula 1 races you would get kind of a half hour edited highlights programme on a Sunday after the race. And that was the main point of engagement. So, you know, here are some cars, here are some drivers, 30 minutes, that’s it. The race is over and done. So, you now have a digital ecosystem that supports it, but the one dimension that we’ve not mentioned so far, which I do think is really significant is you don’t just have drivers and teams taking this seriously, or tracks taking this seriously. You’ve got cities taking this seriously. And you even have now countries taking this very, very seriously.

Kevin Hirten: And nowhere is that more evident than in the Gulf.

[MUSIC PLAYING]

Kevin Hirten: Ever since Bahrain hosted the first Formula 1 race in the Middle East back in 2004, a Grand Prix has been like a shiny new object that every country wants.

Simon Chadwick: Viewed from one angle Formula 1 is still very, very European. So you’ve got a significant number of European drivers, but you also have, most of those teams are based in Europe. But I think Netflix and digital developments have globalised it somewhat, but I think there has been an acceleration of that change with the arrival – firstly of Bahrain, and then a little later on Abu Dhabi, but more recently and more significantly, I think Saudi Arabia, and now Qatar. Just to give you one example, Saudi Arabia is constructing a new sports city, just north of Riyadh.

Announcer: Welcome to Qiddiya. A premier entertainment, sports and arts destination, uniquely Saudi.

Kevin Hirten: This new city is called Qiddiya. The Saudi Public Investment Fund is spending billions of dollars to bring it to life. And they want it to be a home for racing especially.

Announcer: Where young Saudis race fearlessly into the future as they unlock the science and technology of motion and mobility at the motorsports capital of the world.

Simon Chadwick: The Formula 1 Grand Prix in Saudi Arabia will be staged there from 2025 onwards. So you’re talking about a dedicated facility specifically made to stage Formula 1 races costing $500bn.

Kevin Hirten: And creating the track is just one of the expenditures that comes with holding a race. Cities pay for the honour of hosting, as well.

Simon Chadwick: So, certainly if you go back to Ecclestone, races paid Ecclestone for the right to stage a Formula 1 event. And Ecclestone realised that in the Gulf region, the likes of Bahrain and Abu Dhabi, they were prepared to pay huge amounts of money to stage these races.

Kevin Hirten: Compare that to Monaco, one of the places most strongly associated with Formula 1.

Newsreel: A championship race in sunny Monte Carlo. The Monaco Grand Prix, sometimes described as the race of a thousand corners.

Kevin Hirten: Its status has meant that it shells out a fraction of what other spots pay to host a Grand Prix.

Simon Chadwick: So, you began to see a real big disparity between Europeans who weren’t prepared to pay and the likes of Abu Dhabi and Bahrain that were. So, I think we are living in a really interesting period in history where you still do have the remnants and the residue of the old world, but absolutely there is this new world emerging and exerting its presence and its profile on what is, as you said, is a real fast-changing sport.

Kevin Hirten: And on first glance, the Gulf does seem like a natural destination for Formula 1.

Simon Chadwick: There’s something about status and there’s something about prestige, but also linked to that, too, I think they’re, they’re countries with big car cultures. For anybody who doesn’t know anything about car culture in places like Qatar and Saudi Arabia look at YouTube and you’ll see.

[CAR DRIFTING]

Kevin Hirten: There’s tons of videos like this online, showing joyriders doing all kinds of wild stunts while drifting at high speeds in the desert.

[CAR DRIFTING]

Kevin Hirten: But that’s not the only reason why it makes sense for Formula 1 to head to the Gulf.

[MUSIC PLAYING]

Simon Chadwick: These are countries that are producing oil and gas. And of course, you know, Formula 1 uses lots of oil and indirectly uses lots of gas. One of the things that Liberty has been very smart at doing is bringing on board commercial partners, which historically Formula 1 has not had. So, for instance, one of the sponsors have become Saudi Aramco, the state oil corporation of Saudi Arabia. So, hey, you know, that, that kind of makes sense. Here is a country that has all the oil, which is used in Formula 1, Formula 1 is looking for new partners, Saudi Aramco wants to get involved, et cetera, et cetera, et cetera.

Kevin Hirten: Yeah. I mean the real world does still creep in though. I mean, there have been some controversial moments lately, accusations of sports washing. I mean, look at what happened in Russia. They had to cancel the Grand Prix. There were security concerns – I want to ask you about the race in Jeddah.

Simon Chadwick: So, at the race in Jeddah, which took place earlier on this season, a short distance away from the Formula 1 circuit during race weekend. There was a Houthi drone attack on an oil installation.

Newsreel: Developing situation in Saudi Arabia, a large explosion at an oil refinery in Jeddah close to the circuit for this weekend’s Grand Prix.

Newsreel: And the Formula 1 Grand Prix due to take place in Jeddah on Sunday will go ahead.

Simon Chadwick: Saudi Arabia is involved in a hugely fractious war that has resulted in numerous casualties.

Kevin Hirten: Simon’s talking here about the war in Yemen, where a Saudi led coalition has been conducting air strikes for years.

Newsreel: Saudi Arabia forces are targeting Yemen in a series of deadly air strikes.

Newsreel: Yet another air strike killing civilians was blamed on the Saudi led coalition.

Newsreel: As the war in Yemen continues, lawyers representing hundreds of victims have called on the international criminal court to open an investigation into war crimes and crimes against humanity committed by the Saudi-led coalition.

Simon Chadwick: I think the drivers were involved in a, you know, a four- or five-hour meeting to discuss whether or not they wanted to participate in a race that was at risk of attack from Houthi drones. And so, I guess in one sense, this is the new geopolitical reality of Formula 1. What’s significant about all of this is I think what Formula 1, and I think sport in the West historically has tended to do is take a very transactional view of how it engages in relationships. So, of course, why wouldn’t Formula 1 want to go to Saudi Arabia? Saudi Arabia is paying huge amounts of money for the right to do this and is prepared to back the sport. But you know, you take that money, it does come with a price.

[MUSIC PLAYING]

Kevin Hirten: I used the term the sport of the future and I think it kind of threw you a little bit because it is still a very old fashioned sport. I mean, it uses oil. It’s still pretty heavily dominated by white male drivers. There’s a lot of nepotism there. There’s a lot of generational wealth that goes into access to the sport. Yet it is having this moment and it’s resonating in a new kind of global environment that is not always looking at perfect progress.

Simon Chadwick: What you said there about Formula 1 having its moment, I think is really, really important because it could well be that it is just a moment.

[MUSIC PLAYING]

Simon Chadwick: Looking into the future, we know the trajectory of sport and the world, it’s not going to be straight forward for Formula 1. There is a big concern about the degradation of the natural environment. This is a fossil fuel sport, and yet we are talking about cities across the world making announcements like they will no longer sell diesel or petrol cars from 2030 onwards. So, in some ways, the shelf life of it is relatively limited. So I think great, Formula 1 is having its moment, but I think if either Liberty or the fans or anyone else involved with Formula 1 foresees a sustainable future, then they will have to adapt. There is no doubt. It’s almost like a chronicle of transformation foretold. Formula 1 is going to have to change or die, and I think it knows that. so the next 10 years is going to be crucial for sport.

Kevin Hirten: And that’s The Take. This episode was produced by Negin Owliaei with Ruby Zaman, Alexandra Locke, Amy Walters, Chloe K. Li, Ashish Malhotra, and me, Kevin Hirten. Alex Roldan is our sound designer. Aya Elmileik and Adam Abou-Gad are The Take’s engagement producers. Ney Alvarez is the head of audio. We’ll be back.

Episode credits:

This episode was produced by Negin Owliaei with Ruby Zaman, and our host, Kevin Hirten. Ruby Zaman fact-checked this episode. Our production team includes Chloe K. Li, Alexandra Locke, Ashish Malhotra, Negin Owliaei, Amy Walters, and Ruby Zaman. Our sound designer is Alex Roldan. Tim St. Clair mixed this episode. Aya Elmileik and Adam Abou-Gad are our engagement producers. Ney Alvarez is Al Jazeera’s head of audio.