Why do we even have a third-place playoff at the World Cup?

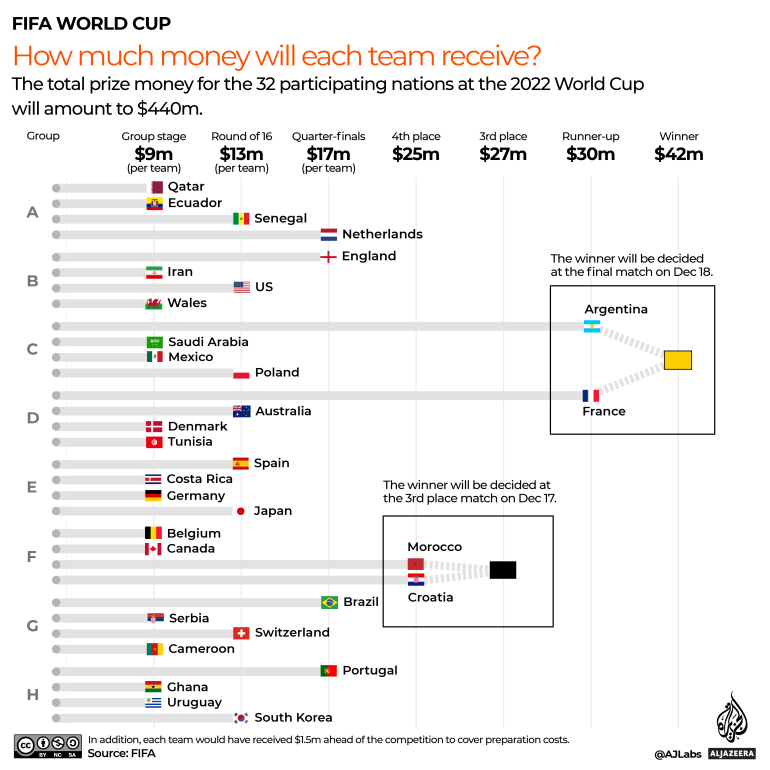

Teams are heartbroken, fans are beyond caring – and it doesn’t even make anyone that much money.

It’s the game that no one wants to play in, it’s the game few may even want to watch.

The World Cup third-place playoff is settling for second best. Well, third best.

Keep reading

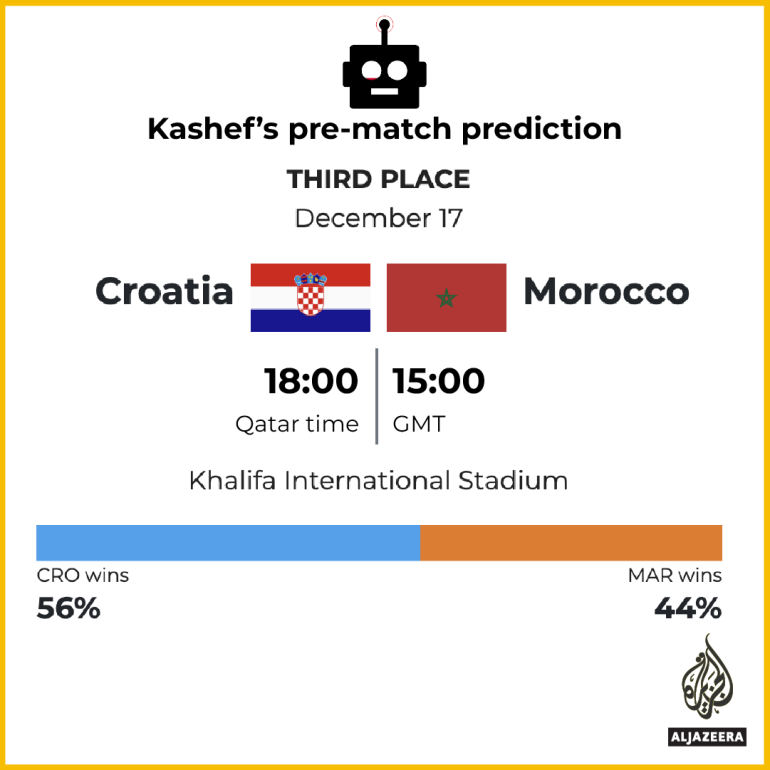

list of 3 itemsMorocco was the feel-good story we did not know we needed

Visualising the FIFA World Cup final

These are teams who have gone all-out, who have trained for years to get to this tournament. These are players who touched down in Qatar with dreams. Not one of the squad members across the 32 teams in Qatar took the field just to show their face. They came to win, to be the best in the world.

Playing for third? Why bother? The dream is over, the trophy is beyond reach.

So, why do we even have a third-place playoff at the World Cup?

“Typically, the third-place playoff provides a mere footnote, or at best some symmetry to decide the better of the two semifinalists vanquished by the last two remaining teams left in the tournament, upon whom the eyes of the world will be as they compete to be crowned world champions,” David Webber, a researcher into the cultural and political economy of football at Solent University, told Al Jazeera.

“But [it] does, however, serve a sporting purpose. At the very least, a shot at redemption, and an opportunity to celebrate the achievement of reaching the last four of the competition. Rarely are these games short on entertainment either, with four out of the last seven bronze medal games, since 1994, seeing four goals or more. With nothing to lose, teams will often go on the attack – with strikers after the Golden Boot often the main beneficiaries.”

This “bronze medal” idea plays into a wider sense of sporting history.

“The origin of the World Cup was very much influenced by the Olympics, and the ideology there was always gold, silver and bronze,” said Paul Widdop, a sport business academic at the University of Manchester. “This is then reflected in the way the World Cup is organised. It’s similar to why we have a four-year World Cup cycle, based on outdated Greek mythology.”

FIFA makes money from ticket sales. An extra match means at least 45,000 more people in Khalifa International Stadium, each paying between $80 (for Qatari residents) and $425. That’s a fair chunk of change. Qatar 2022 helped boost FIFA’s income by more than $1bn to over $7bn for this four-year cycle.

There must also be little appeal for sponsors, who would sooner be associated with the showpiece final rather than a game that for many fans and players offers little consolation.

As an example of just one TV market, in 2018, about 9.8 million United Kingdom viewers tuned in to watch England lose the third-place playoff to Belgium, Widdop noted. More than 26.5 million – 40 percent of the UK’s population – had watched England’s previous game: the semifinal defeat at the hands of Croatia. And that’s just people who watched at home.

Whether it’s about squeezing the last few riyals out of the tournament or stretching the last sinew of competition – to finish third is better than finishing fourth, after all. The match is a chance to celebrate those who came so close to football’s greatest glory.

FIFA President Gianni Infantino called Qatar 2022 the “best World Cup ever”. And this year, with the fairytale run of Morocco, and the likely departure from the international stage of Croatia’s heroic Luka Modric, with the devastation of semifinal defeat still raw, there’s one more chance to go home on a high.