Illegal wildlife trade goes online as China shuts down markets

Online shift increases pressure on China’s tech giants over trade thrust into spotlight by coronavirus outbreak.

Shenzhen, China – China’s top e-commerce and express delivery operators are under pressure from the government and wildlife activists to become de facto enforcers of the country’s temporary ban on the trade in wildlife.

The ban was imposed in late January as cases of COVID-19 surged in Wuhan, where the now global pandemic was suspected to have originated in the wildlife trade or from animals trafficked into the country from abroad.

Keep reading

list of 3 itemsCoronavirus: Why so many deaths in Italy?

Grief, anger in China as doctor who warned about coronavirus dies

At the same time, however, conservation groups are calling on China to fully overhaul the way it governs the country’s lucrative business in order to give firms more clarity over what to target when they discover any potentially illegal activity.

In the first month of the ban, e-commerce platforms aided in the removal, deletion or blocking of information relating to 140,000 wildlife products from bush meat to animal parts used in traditional Chinese medicine, and closed down about 17,000 accounts associated with the trade, an official from China’s State Council said in late February.

The country’s Ministry of Transport has also now ordered express delivery companies to be the first line of defence in stopping transport of live animals and other wildlife products, requiring them to take extra care to inspect packages before they are shipped.

Promise to stamp out trade

China has pledged to revise the laws governing the wildlife trade, estimated in value at $74bn, according to a Chinese Academy of Engineering report released in 2017, although the changes appear to only target the consumption of meat from wildlife.

This would mean the fur and leather industry, as well as the trade in animal parts procured for traditional Chinese medicine (TCM) could carry on as usual. This would allow for the trafficking of endangered or protected species. Animals known to carry viruses that can jump from animals to humans such as those that might have caused COVID-19, could also fall under the radar, conservation groups say.

“Right now, there isn’t enough regulation specifying the responsibility of online platforms,” Zhou Jinfeng, head of the China Biodiversity Conservation and Green Development Foundation told Al Jazeera.

“If they don’t play their role and are not able to step up their monitoring mechanisms, stopping online wildlife trade will be difficult,” he said. “I hope the government can come up with rules to urge online platforms to take their responsibility.”

Over the past few weeks Zhou’s group and a network of volunteers have been helped by companies like Alibaba, Tencent, JD.com and others in a “Wildlife Free Ecommerce” campaign targeting online sales, as well as hunting tools such as bird-catching nets, bird-call machines, wildlife snares and traps and torches specifically used for hunting scorpions.

Zhou is also pressing authorities in Beijing to implement a corporate social credit system to reward or punish e-commerce companies for their part in combatting the illegal wildlife trade and hopes that by pressuring the leading companies they will be able to set the example for other smaller players. Similar systems are being used to evaluate companies across China, including by the Ministry of Ecology and Environment to discourage breaches of environmental regulations.

Grace Gabriel, Asia Director of the International Fund for Animal Welfare (IFAW) told Al Jazeera that the large companies have already long set precedents for combating illegal wildlife trading.

Gabriel has been working with Alibaba since 2007, when the company first began action to remove elephant ivory, tiger bone, bear bile and rhino horn from the Taobao shopping platforms and later when they did the same with pangolin scales and shark fins.

Licensing loopholes

IFAW, along with Worldwide Fund for Nature (WWF) and wildlife monitoring group TRAFFIC, joined companies including Alibaba and Tencent in 2017 to form the Coalition for Wildlife Trafficking Online which aims to reduce online wildlife trafficking by 80 percent by the end of 2020.

Key will be changing China’s licensing system, which until the recent ban had allowed 54 species of wildlife and the meat and animals parts to be legally raised, sold and traded.

Those legal licences allow some leeway for loopholes that are often at odds with the Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species of Wild Fauna and Flora (CITES), to which China is a signatory.

“That licence basically became a commodity itself that can be sold,” Gabriel said. “People catch wildlife from the wild and then launder them through the [licenced] legal market.”

Gabriel says reforms are necessary to help online platforms know exactly what is legal or prohibited.

Steve Blake, head of the Beijing office for non-profit group WildAid has been working with Tencent and other platforms in recent years on how to combat the trade, but says companies faced difficulties not only because of the uncertainty over whether it was legal but also because of data privacy issues.

Tencent representatives declined to comment when approached by Al Jazeera, and Alibaba and JD.com did not respond to requests to discuss the difficulties they face in monitoring and policing the wildlife trade.

Blake says the government needs to clarify what species are off-limits and upgrade its laws to provide for better enforcement.

“It’s going to take some time to go from a pretty confusing and outdated system into quickly ramping it up and having strict oversight, strong enforcement and clear guidelines,” he said.

Central to managing the trade is also being able to trace and track the sale of all wildlife, as the COVID-19 outbreak was thought to have stemmed from the creatures being sold at the Wuhan market in Hubei province, the epicentre of China’s virus outbreak.

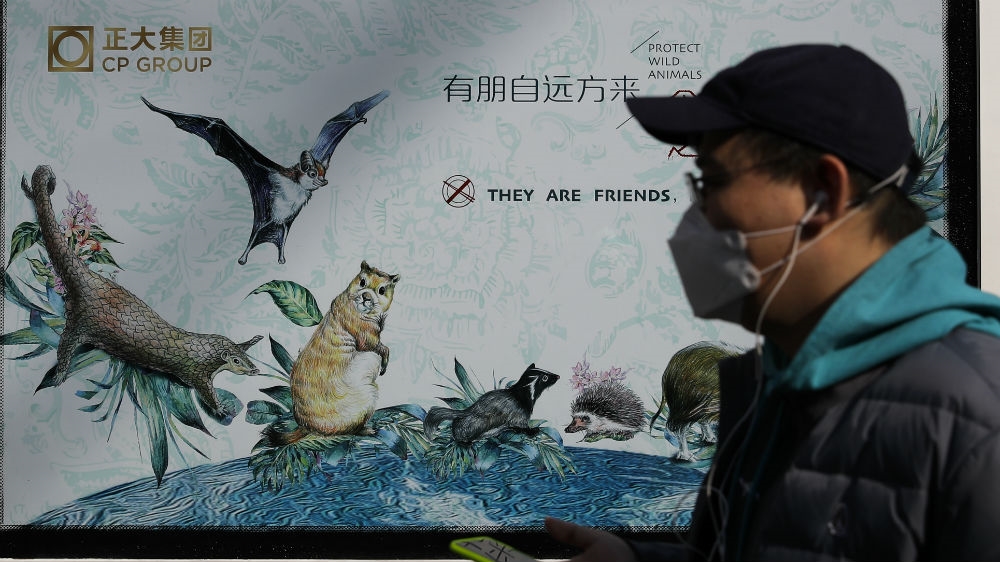

Pangolins, bats and other wildlife known to transmit coronaviruses have been named as possible carriers of COVD-19, but no evidence has been provided by China’s Center for Disease Control and Prevention or other health authorities in the country to pinpoint the exact source.

China’s authorities have not provided any information regarding the epidemiological investigation into the Wuhan South China Seafood Market where the virus possibly jumped from animals to humans, sites where animals were raised or the supply chains, a World Health Organization (WHO) spokesperson told Al Jazeera.

The market in Wuhan was closed in January, but it is still not known what was done with any of the animals there and whether authorities were able to do a proper investigation before the facility shut down.

A spokesperson for China’s Ministry of Foreign Affairs did not answer requests for further information about the investigation into the animal source when approached by Al Jazeera on March 20.

Richard Thomas, a spokesman for TRAFFIC, told Al Jazeera that the legality surrounding the wildlife trade itself was not that much of an issue. Far more crucial were the conditions surrounding the trade which may have given rise to diseases like SARS, Ebola and now the COVID-19 virus.

“Worldwide governments face a dilemma here: If you ban trade, you risk pushing it underground, where those dangerous conditions are likely to be prevalent – and realistically it’s just a matter of time before the next zoonotic disease risk emerges,” Thomas said. “If you manage legal trade properly, the risk of disease emergence should be mitigated but it needs to be thoroughly monitored and regulated.”

It will be important for China to decide which route it will take in that regard, he said. Either path will need considerably more resources for monitoring and policing, not only of the trade itself, but also the health risks posed by the animals during the entire process from the breeding of the creatures to transporting them and their sale.

A well-monitored and regulated trade, at whatever level, would be much safer than an underground one.

“If there is a silver lining [from the outbreak], it’s that people will realise this is not just a conservation issue any more,” Gabriel said. “It’s much bigger than that.”

Additional reporting assistance provided by Zhong Yunfan