Sea crew change restrictions endanger workers and supply chains

Thousands of seafarers are stranded at sea at increased risk of COVID-19 – or trapped onshore unable to earn a living.

Travel restrictions amid the coronavirus pandemic have left seafarers stranded at sea, at heightened risk of infection, or trapped onshore facing financial uncertainty.

Coronavirus-related travel restrictions are preventing people who work on ships from disembarking, and their replacements from boarding. The result is painful: Trapped on ships, seafarers are at heightened risk of infection and mental illness; those forced to stay onshore are unable to support their families, while consumers could face import shortages. To keep the world supplied with goods that are shipped by sea, industry bodies are calling for seafarers to be classified as essential workers.

Keep reading

list of 4 itemsMexico’s teachers seek relief from pandemic-era spike in school robberies

‘A bad chapter’: Tracing the origins of Ecuador’s rise in gang violence

Why is the US economy so resilient?

Rajiv is chief engineer aboard a cargo ship making its way along the Suez Canal, heading for Dahej port in India. He agreed to talk to Al Jazeera if his last name was not published. The 45-year-old is part of a largely unseen 1.2 million-member workforce that works 12-hour shifts on ships to ensure the safe passage of 80 percent of global trade.

Contract extensions spell uncertainty

Rajiv’s contract expired three weeks ago. He wants to go home to Noida in India, but his country has blocked all international crew changes for fear that infected seafarers will unwittingly spread the virus. Rajiv’s experience reflects a new, coronavirus-laced reality for sea workers around the world. Travel restrictions imposed by governments trying to contain the pandemic’s spread are preventing crew changes.

Every month, 100,000 seafarers need to rotate on and off ships to comply with the Maritime Labour Convention. To keep the fleet of 50,000 to 60,000 vessels moving, the industry has imposed a one-month extension on all seafarer contracts that expired in March. That extension, however, is almost up and it is still not clear when seafarers will be allowed to go home.

“We don’t know how much more time we have to spend at sea before we meet our families,” Rajiv told Al Jazeera via text message.

‘Impending crisis’ for global trade

“The problem is simplistic, but the solution is complex,” said Guy Platten, Secretary-General of the International Chamber of Shipping (ICS). Last month the ICS issued a call to the Group of 20 coalition of nations to allow seafarers to freely move. The United Nations Conference on Trade and Development (UNCTAD) made a similar plea for restrictions to be lifted to maintain global cross-border trade.

Platten told Al Jazeera that he fears travel restrictions will persist even when countries start to relax domestic lockdowns. “This is an impending crisis. We’ve got to start getting governments to classify seafarers as essential workers. We need these people to keep the world supplied.”

“For a lot of shipowners, crew tends to be the last thing on their minds,” said Steve Trowsdale, the inspectorate coordinator for the International Transport Workers’ Federation (ITF). “We think we’ve got problems with goods on shelves now. What do you think will happen if ships stop delivering goods?”

We don't know how much more time we have to spend at sea before we meet our families.

The industry is already feeling the squeeze. Europe’s largest port, Rotterdam in the Netherlands, reported an “unprecedented” decline in first-quarter throughput figures, which measure the volume of goods passing through the port. In a statement, Rotterdam port chief executive Allard Castelein said he expected full-year throughput to fall by up to one fifth. The port of Los Angeles in the United States saw March throughput plunge 30 percent on the previous year, while Singapore and Hong Kong reported similar declines.

Mandarin Shipping Ltd’s codirector Tim Huxley said crew change restrictions had led to sailing cancellations and employment delays. Dario Alampay, chairman of the Filipino Shipowners Association, expects fewer available ships and higher freight costs.

There is some hope on the horizon. Last week, an alliance of shipowners that includes Grieg Star, Wilhelmsen Ships Service, and Synergy Group came together to pressure governments. The alliance, which represents 1,500 vessels and 70,000 seafarers, is now identifying ports where crew changes could be safely carried out.

Health hazards from onshore

Some seafarers with expired contracts have had little choice but to accept the extension. Stanislaw, a 36-year-old officer from Poland who asked not to be identified by his real name, was ready to head home to his wife and young daughter this week, but he is now in Colombia, loading up a bulk carrier with coal, which will be unloaded in Guatemala.

Speaking to Al Jazeera over the phone from onboard, Stanislaw said he preferred to remain at sea rather than risk infection on the journey home. “I would have to cross through airports, where there is a lot of risk. I don’t want to bring any hazard home.”

While he and his crew are currently free of infection, Stanislaw fears transmission by dockworkers and port pilots who come aboard during loading and discharging.

At Rio Haina in the Dominican Republic, although port officials requested his ship be thoroughly sanitised before docking, the pilots who boarded to inspect the ship were not sufficiently equipped with gloves and masks.

“They were touching everything. What’s the point?” asked Stanislaw.

“They ask us to keep the ship to ‘hospital standard,’ but nobody protects us from their stupidity. We’re not the hazard for them; they’re the hazard for us.”

Onboard a ship, the coronavirus travels fast. An outbreak on the American military vessel USS Theodore Roosevelt resulted in a death on April 14th. And before COVID-19 had even reached Europe, the spread of the virus on cruise ships was dominating headlines. More than 1,000 sailors assigned to a French aircraft carrier tested positive for the coronavirus in April. French military officials believe sailors contracted the virus after they disembarked for shore leave at the port of Brest shortly before France’s lockdown.

Financial insecurity

It is not only those at sea who are affected. Seafarers are employed on a “per voyage” basis, earning only as long as they are on board. Thousands are currently under lockdown in India, the Philippines and Eastern Europe, unsure when they will next join their ships and how they are going to make a living.

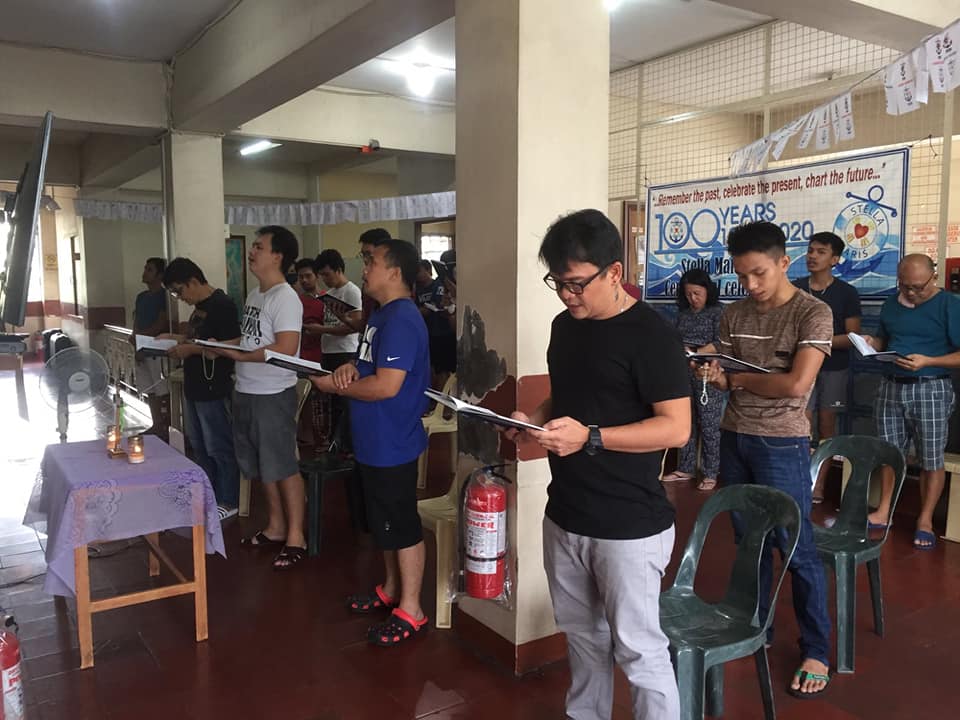

Roberto is one of 120 seafarers stranded at a hostel run by global maritime charity Stella Maris in the Philippines. He’s in his 50s and has worked at sea for 14 years. One month ago, he was preparing to fly to Cyprus to join a ship. Now under lockdown and not earning money, he is worried about his family.

“I want to go back to my ship because my daughter has to get her education. I need money very bad,” he said over video call. “I miss them, but for the sake of my family, I must wait here.”

Mental health risk

“Seafarers describe being at sea as being in prison,” says Professor Helen Sampson, director of the Seafarers International Research Centre at Cardiff University in Wales in the United Kingdom. She led a study into mental health at sea, published in November 2019. Most of the 1,500 participants cited the day they left a vessel as their happiest day on board.

According to the Maritime Labour Convention, the maximum time a seafarer can spend at sea is 12 months. Living on a boat for too long can negatively affect mental health. That is why, per a collective bargaining agreement by the ITF, seafarers can work nine months plus or minus one month at sea for unforeseen circumstances.

Sampson predicts indefinite contract extensions – caused by efforts to contain the pandemic – are likely to heighten short-term anxiety, incidences of depression, and compound “the stress and worry that all humans feel as a consequence of the pandemic”.

Back aboard a coal ship at the port in Colombia, Stanislaw is trying to stay positive. “I tell myself that I’ll go home [at the] beginning of May,” he says. “Let’s just keep fingers crossed that it will work out.”