Lula’s political comeback adds to investors’ worries in Brazil

The Brazilian real is down 11 percent so far this year, the worst among major currencies, as a raging virus outbreak brings new lockdowns and increases pressure for the government to shift away from cost-cutting pledges.

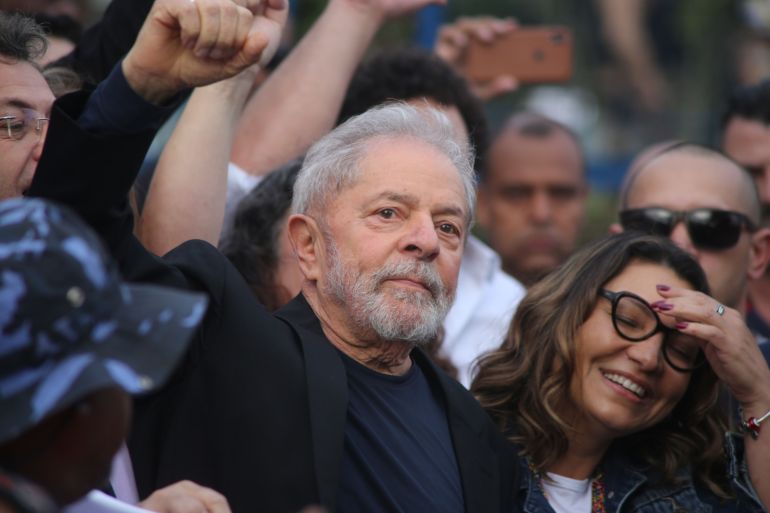

Luiz Inacio Lula da Silva was thrust back into Brazil’s political scene after a judge tossed out criminal convictions against the leftist icon, adding to investor concerns that the country’s reform agenda may be derailed by early campaigning for the 2022 presidential election.

The federal court in the southern city of Curitiba had no jurisdiction over cases against the former president, including ones that led to sentences for bribery, Justice Edson Fachin wrote in a statement on Monday. The news sent stocks and the currency cratering, deepening some of the worst performances this year at a time congress discusses approving extra emergency spending to alleviate a renewed coronavirus outbreak.

Keep reading

list of 4 itemsIn Pictures: Brazil’s women suffer as COVID limits abuse reports

‘Catastrophe’ as Brazil hits record-high daily COVID deaths

‘Situation is alarming’: Brazil sees new daily COVID death record

Markets recovered some of the losses on Tuesday amid a strong bounce in global assets and as fears fiscal austerity measures would be watered down were dispelled by lawmakers. The currency rose 0.1% as of 1:40 p.m. in Sao Paulo, while the Ibovespa climbed 1.3% — both still trailed peer.

The decision provides the biggest chance yet at a long-sought comeback for a highly controversial figure in Brazilian politics. While Lula remains revered for lifting millions of citizens out of poverty, many also say he is a symbol of corruption and economic mismanagement. The four consecutive governments of his Workers’ Party ended abruptly in 2016 with the impeachment of Lula’s hand-picked successor, Dilma Rousseff.

The ex-president scheduled a press conference for Wednesday morning at his former union headquarters in a working class suburb of Sao Paulo — the place where he hunkered down when then-Carwash judge Sergio Moro ordered his arrest back in 2018. The conference was initially expected for Tuesday, but Lula rescheduled it while the Supreme Court decides when to resume discussions on whether Moro was fit as a judge.

“I see a 80%-90% chance that Lula will be able to run by July 2022, which is the deadline for candidates to register with the electoral court,” said Debora Santos, a political analyst with XP Investimentos. “We’re in another context that favors Lula.”

Yet there are are no shortage of hurdles for Lula, 75, to return to the nation’s top job. His candidacy in next year’s vote hinges on whether the courts have time to re-try the former president from scratch — a tall order given Brazil’s notoriously bureaucratic legal system. In order to be ineligible by Brazilian law, as it happened in the 2018 presidential election, he would have to be convicted and have the ruling upheld by an appeals court.

Brazil’s top prosecutor’s office also plans to appeal Fachin’s decision, potentially setting off a protracted legal battle, newspaper O Globo reported, without saying how it obtained the information.

Election Kickoff

Lula’s return to the electoral agenda brings forward an election debate that wasn’t expected for months. While the Brazilian economy boomed under the former president’s first years in office, largely benefited by higher commodities prices and his plans to redistribute income, it started suffering as Rousseff pivoted to interventionist policies to artificially rein in inflation and lower interest rates.

“Brazil’s 2022 election began today,” said Thomas Traumann, a Rio de Janeiro-based communications consultant who has advised past ministers and presidents. “Lula today won’t be the same Lula in 2002, with a market-friendly message of peace and love. He will seek revenge, and he will blame the markets, the media and business leaders for the downfall of the Workers’ Party.”

The possibility of a repeat of the polarization seen in the election of 2018, when Bolsonaro faced off Lula’s handpicked candidate Fernando Haddad, is another wrench in what already has been a tumultuous start of the year for Brazilian markets.

The real is down 11% so far this year, the worst among major currencies, as a raging virus outbreak brings new lockdowns and increases pressure for the government to shift away from cost-cutting pledges. Bolsonaro’s administration has bypassed public spending rules deemed essential by investors, financing emergency aid packages that provide temporary relief but no permanent solution to the pandemic’s toll on Latin America’s largest economy.

“If Lula is able to run again, the reform agenda would likely be off the table and the prospects for fiscal discipline would deteriorate,” said Brendan McKenna, a strategist at Wells Fargo & Co. in New York. “Markets place a lot of weigh on fiscal austerity when it comes to Brazil.”

On top of that, investors must now confront odds of the rise of the charismatic, anti-austerity crusader. An eventual race between Bolsonaro and Lula would create a “polarized election that will be decided by those who dislike Lula or Bolsonaro less,” said Creomar De Souza, chief executive officer of Brasilia-based consultancy Dharma Political Risk and Strategy.

Lula’s presence would also make it harder for a centrist candidate to gain traction, Eurasia Group wrote in a note.

Not everyone was rattled by the news.

“Lula presided over some of the happier times in Brazil, his program to give money to the poor, send children to school was very popular,” veteran emerging market investor Mark Mobius said on Boomberg TV. “I don’t think Lula returning will necessarily be bad for Brazilian markets. I think he’s learned his lesson as regards to corruption.”

Direct Ties

Lula has repeatedly denied wrongdoing and said he is the victim of political persecution. The cases against the former president shouldn’t have been carried out in Curitiba because the facts that were raised don’t have direct ties to the misappropriation scheme at Petroleo Brasileiro SA, Fachin wrote in Monday’s statement.

Since 2014, the Brazilian oil producer known as Petrobras has been at the center of the Carwash probe, the country’s largest anti-corruption investigation. In that context, the cases against Lula must be tried in court in the capital city of Brasilia, according to Fachin.

The judge’s decision is in sync with defense arguments made over the past five years, Lula’s lawyers Cristiano Zanin Martins and Valeska Teixeira Zanin Martins said in a statement. “Ex-President Lula was jailed unjustly, had his political rights unduly taken away and his property blockaded,” they wrote.

Bolsonaro criticized the ruling, saying the judge has strong ties with the Workers’ Party — Fachin was appointed to the Court by Rousseff.

“Brazilians don’t want someone like this to run in 2022. It was a catastrophic government,” Bolsonaro told reporters at the official residence in Brasilia on Monday.

Political Force

Even while out of the spotlight, Lula has proved he can remain a political force to be reckoned with. A poll released this weekend showed Lula has more potential ahead of the 2022 elections than Bolsonaro.

The survey carried out by Ipec showed 50% of respondents said they may vote for Lula in the 2022 elections if he were to run, versus 38% for Bolsonaro. Lula also showed a lower rejection rate when compared to Bolsonaro — 44% to 56%, respectively.

“Lula has to assume his position as Bolsonaro’s main rival and join forces to face this disaster of a government,” said Senator Humberto Costa, a close ally of the leftist leader.