The US spent $2 trillion in Afghanistan – and for what?

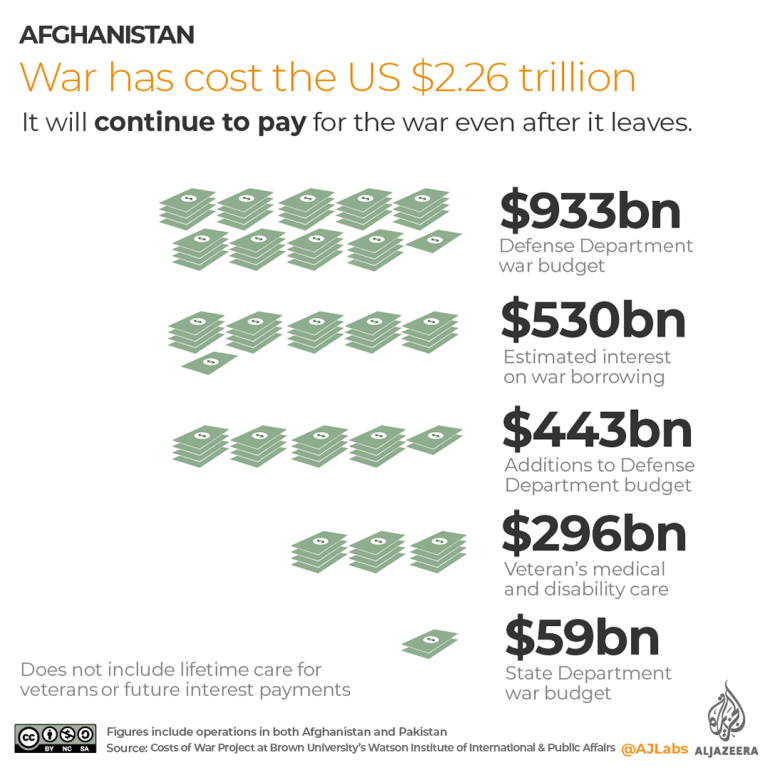

Since 2001, the United States has spent $2.26 trillion in Afghanistan, the Costs of War Project at Brown University calculates – an investment that has yielded a chaotic, humiliating end to America’s longest war.

There is no shortage of benchmarks to count the cost of the United States’ longest war. Blood is by far the most precious metric. Treasure feels insignificant by comparison. But as images of Afghans swarming Kabul airport, desperately trying to flee Taliban rule, flood screens around the world, the vast sums the US spent trying to build Afghanistan into a liberal democracy deserve a thorough audit. Otherwise, lessons may be forgotten and tragic mistakes repeated.

The bedrock of any nation-building effort is security. If people don’t feel safe, instability, graft and corruption flourish while the formal economy withers.

Keep reading

list of 4 itemsByteDance prefers TikTok shutdown in US over sale: Report

‘We need you’: Solomon Islands’ support for US agency’s return revealed

Why are nations racing to buy weapons?

Back in 2001, Afghanistan’s economy lay in ruins due to more than two decades of war that predated the US-led invasion in October of that year.

Since 2001, the US has spent $2.26 trillion in Afghanistan, the Costs of War Project at Brown University calculates. The biggest chunk – nearly $1 trillion – was consumed by the Overseas Contingency Operations budget for the Department of Defense. The second biggest line item – $530bn – is the estimated interest payments on the money the US government borrowed to fund the war.

Yet for all those trillions, Afghanistan still has one of the smallest formal economies on the planet. Last year, President Ashraf Ghani said 90 percent of the population was living on less than $2 a day.

The illicit economy, meanwhile, has boomed. After US forces drove the Taliban from power in 2001, Afghanistan cemented its place as the leading global supplier of opium and heroin – a crown it is likely to keep as the Taliban emerge victorious again.

If that return weren’t poor enough for the US, the Afghan army and the government it was meant to protect have now collapsed. President Ashraf Ghani has fled the country and the Taliban are taking selfies behind his desk. This is what a $2 trillion investment has yielded for the US: a chaotic, humiliating end to a 20-year war.

A grim ledger

Since 2001, the US has appropriated more than $144bn to Afghan reconstruction. Much of that money went to private contractors and NGOs the US government tasked with implementing programmes and projects to build Afghanistan’s security forces, improve governance, aid economic and social development and combat illicit drugs.

The most critical failure of those reconstruction efforts – and the most expensive – was the $88.3bn spent training and equipping the Afghan army from May 2002 to March this year.

The Afghan army was tasked with repelling the Taliban and other armed groups like al-Qaeda and ISIL that posed an existential threat to the US-backed Afghan government. But the swiftness with which the 300,000-strong force laid down arms in the face of the Taliban’s advance betrayed how little faith the country’s soldiers had in the institution they served and the national government they had sworn to defend.

Afghanistan’s unique historical and cultural factors undoubtedly helped shape that outcome. But poor monitoring and evaluation of US efforts are also to blame for throwing good money after bad.

That is why the US Congress created SIGAR – the Special Inspector General for Afghanistan Reconstruction. Since 2008, it has been auditing and assessing Washington’s reconstruction efforts in Afghanistan. The reports it churns out have been notable for their prescience and their propensity to pull no punches when it comes to highlighting waste, fraud and abuse.

For example, a 2017 report on US efforts to train Afghan security forces found that Washington’s “politically constrained” timelines “consistently underestimated the resilience of the Afghan insurgency” while overestimating the capabilities of Afghan government forces. The US also erred, said SIGAR, by trying to graft advanced western weapons and management systems onto a largely illiterate fighting force – perpetuating Afghan dependence on US forces rather than creating an Afghan army that could stand and fight on its own. SIGAR also found that the tools that were used to monitor and evaluate the progress of US training efforts masked “intangible factors, such as corruption and will to fight”.

Last month, SIGAR published its 10th report on “Lessons Learned” in Afghanistan. “In unpredictable and chaotic environments such as Afghanistan, poor oversight or improper implementation can threaten relationships with local communities, endanger the lives of U.S. and Afghan government personnel and civilians, and undermine strategic goals,” Inspector General John F Sopko wrote in the executive summary.

At 324 pages, the report makes for dense but important reading. Having had a front-row seat to the slow-motion train wreck of American involvement in Afghanistan, Sopko highlighted where the real impact of his office’s work would likely be felt.

“It is almost axiomatic that the United States periodically becomes involved in large-scale reconstruction efforts,” he wrote. “Should the United States find itself involved in another — even several years or decades from now — the findings, lessons, and recommendations presented here may prove useful.”

Useful indeed. For Afghanistan, though, those lessons have come too late.