After ‘bridge to Europe’ bid, Ukraine’s China ties face test

Beijing’s reluctance to condemn the invasion of Ukraine complicates a burgeoning partnership with the Eastern European country.

Last July, Ukrainian President Volodymyr Zelenskyy made a bold offer to his Chinese counterpart Xi Jinping. On a phone call to mark the 10th anniversary of a strategic partnership between the two countries, Zelenskyy said he wanted Ukraine to become a “bridge to Europe” for Chinese companies.

Seven months later, that hope is being tested in the crucible of Europe’s gravest security crisis since the end of the Cold War, with Russia on Thursday launching a full-scale military offensive against Ukraine.

Keep reading

list of 4 itemsHong Kong turns to emergency powers for China help in COVID surge

Russian forces launch full-scale invasion of Ukraine

‘Drivers have died’: South Korea’s couriers camp out for change

Since 2019, China has been Ukraine’s top trading partner, taking pole position from Russia amid tensions between Kyiv and Moscow. Despite the pandemic, trade between China and Ukraine has grown over the past two years, reaching $15.4bn in 2020 and nearly $19bn in 2021, according to the Ukrainian government’s customs data.

China also views Ukraine as a pivotal transit hub and node for Xi’s Belt and Road Initiative, a global web of highways, train routes and ports built with loans from Beijing. A direct train connecting the two nations started last June.

But China’s reluctance to condemn Russian President Vladimir Putin’s announcement of an invasion into eastern Ukraine could complicate this burgeoning partnership, while also injecting fresh uncertainty into economic ties with Europe and the United States, experts say.

“Uncertain and problematic” is how Vasyl Yurchyshyn, director of economic programmes at the Razumkov Centre, a Kyiv-based think-tank, described the current state of China-Ukraine ties to Al Jazeera. “Ukraine is going to continue economic cooperation with China, but its effectiveness and efficiency will completely depend on China and its willingness to support our country,” he said.

Fine balance

So far, China has attempted to strike a fine balance in the Ukraine crisis. It has supported Russia’s security demands, including Moscow’s insistence that NATO abstain from any further eastward expansion. On Wednesday, it criticised Western sanctions against Russia, accusing Washington of “creating fear and panic”. It has blamed NATO for the tensions in Europe. But it has also emphasised that it does not support an invasion of Ukraine.

“The sovereignty, independence and territorial integrity of any country should be respected and safeguarded,” Chinese foreign minister Wang Yi said last week, addressing the Munich Security Conference. “Ukraine is no exception.” On Thursday, Chinese foreign ministry spokeswoman Hua Chunying called on all parties to exercise restraint, but rejected a journalist’s description of Russia’s actions as an invasion.

Analysts believe that this diplomatic juggle is aimed, in large part, at trying to insulate China from any economic backlash from the United States and the European Union. “That is something that worries Xi Jinping,” Trey McArver, co-founder of Trivium China, a Beijing-based strategic advisory firm, told Al Jazeera.

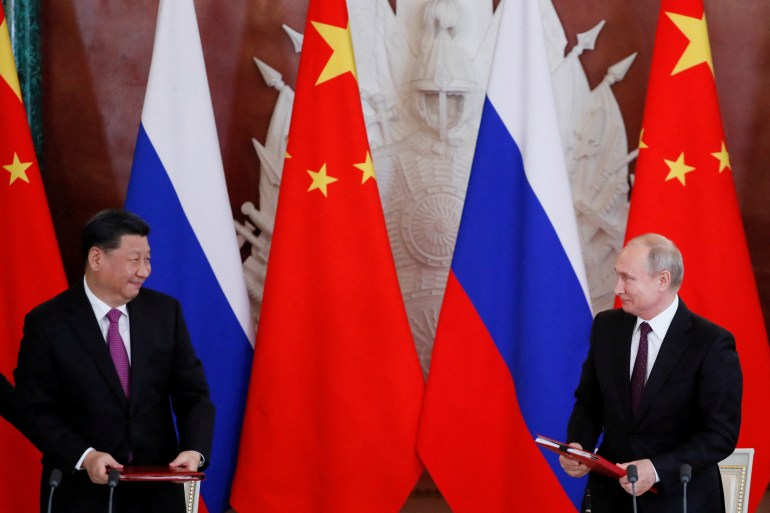

After Xi and Putin released a joint statement earlier this month stating that friendship between Beijing and Moscow has “no limits,” the US national security adviser, Jake Sullivan, warned that China too could face “costs” if it is seen as being supportive of Russian aggression against Ukraine.

“I think that concern is part of what is motivating Beijing to thread the needle in its messaging on the conflict,” Jessica Brandt, a fellow at the Brookings Institution, told Al Jazeera.

Economic relations between Beijing and the West have already taken a severe beating in recent years. Concerns over trade barriers, currency manipulation and data privacy in Chinese tech have melded into broader tensions over human rights abuses in Xinjiang, Beijing’s crackdown on dissent in Hong Kong and its threats against Taiwan.

The European Union suspended a free trade agreement with China last year, while Beijing and Washington are yet to meaningfully roll back measures they took against each other during the trade war launched by former US President Donald Trump.

Yet things could get even worse for China because of the Ukraine crisis, according to analysts. “Especially with the European Union, I think the economic relationship might suffer,” Li Mingjiang, associate professor at the S Rajaratnam School of International Studies at Singapore’s Nanyang Technological University, told Al Jazeera.

At the same time, Western sanctions are likely to increase Russia’s economic dependence on China. Their bilateral trade, which stood at $104bn in 2020, is poised to increase as Russia relies on its southern neighbour’s vast market even more. After meeting with Xi in Beijing in early February, Putin announced a new pipeline that will supply China with 10 billion cubic metres of gas every year, in addition to the 16.5 billion cubic metres Russia already sends.

All of this gives China leverage that it could use to seek or renegotiate deals with Russia for terms that are even more favourable for Beijing. Some analysts believe Xi is likely to refrain from exercising this option. “He definitely has the circumstances that would allow him to press home his advantage with Russia,” said McArver, from Trivium China. “However, I don’t see him doing it.”

China would not want to disrupt its relationship with Moscow, said Brandt. That is also true for Beijing’s economic ties with Kyiv, according to Li of the S Rajaratnam School of International Studies.

The relationship is easy to overlook because the volume of trade between China and Ukraine – while massive for the Eastern European nation – is small compared with the flow of goods and services between big nations. But Ukraine supplies the spare parts and maintenance services for a range of Russian-made Chinese planes, a legacy of the haphazard collapse of the Soviet Union that left its vast aerospace and aviation sector divided between two countries. Ukraine is also among China’s biggest sources of corn.

Deeper dilemma for China

“China values this relationship,” Li said. “That’s why, if you read between the lines, it has effectively criticised Russian aggression.”

But many Ukrainians may not be willing to parse through diplomatic nuance as their country is under attack.

“In international forums, which address issues important to Ukraine, the United States and European partners show consistent support for Ukraine,” said Yurchyshyn of the Kyiv-based Razumkov Centre. “China, on the other hand, often takes a far from pro-Ukrainian position, primarily on issues of countering Russian aggression … can this be really ignored?”

To be sure, scaling back on economic ties with China would likely hurt Ukraine more in the short term – trade between the nations constitutes 11 percent of Ukraine’s gross domestic product.

Yet recent history offers examples of Ukraine adapting when it needs to. In 2014, when Russia annexed Crimea, Ukraine’s economy depended even more on its large neighbour than it does on China today. The sharp decline in trade with Russia that followed helped Ukraine’s economy become more competitive, Yurchyshyn said.

Ultimately, the current crisis exposes a deeper dilemma for China, said Brandt. Moscow and Beijing share an animus against liberal institutions and governments that challenge them, she said. But they have different long-term strategic goals.

“Russia is a declining power that seeks disorder. China is a rising power that wants to reshape the existing order to suit its interests,” Brandt said.

Beijing’s choices over the next few weeks could help dictate what that world order looks like.