Facebook charged BJP less for India election ads than others

The cheaper rates allow the BJP, Facebook’s largest political client in India, to reach more voters for less money.

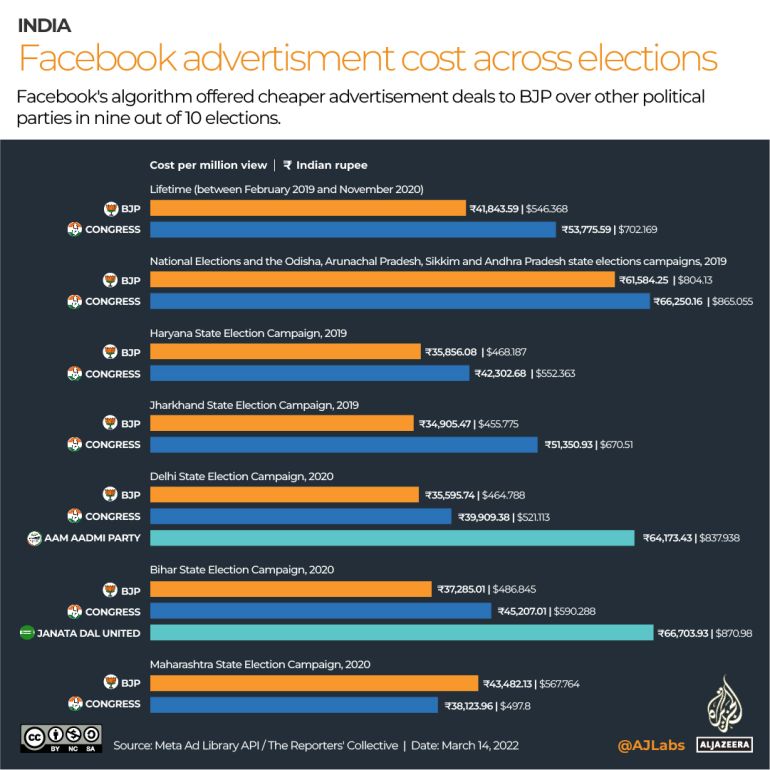

New Delhi, India–Facebook’s algorithm offers cheaper advertisement deals to India’s ruling Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP) over other political parties, according to an analysis of advertisement spending spread across 22 months and 10 elections. In nine of the 10 elections, including the national parliamentary elections of 2019 that BJP won, the party was charged a lower rate for advertisements than its opponents.

The favourable pricing allows the BJP, Facebook’s largest political client in India, to reach more voters for less money, giving it a leg up in the election campaigns.

Keep reading

list of 4 itemsFacebook to restrict access to Russian state media outlets in EU

Facebook, Instagram demoting posts from Russian state-media

Russia blocks access to Facebook amid war with Ukraine

The Reporters’ Collective (TRC), a non-profit media organisation based in India, and ad.watch, a research project studying political advertisements on social media, analysed data for 536,070 political advertisements placed on Facebook between February 2019 and November 2020. They accessed the data through the Ad Library Application Programming Interface (API), Meta Platforms Inc’s ‘transparency’ tool that allows access to political advertisement data across its platforms.

On average, Facebook charged the BJP, its candidates and affiliated organisations 41,844 rupees ($546) to show an ad one million times. But the main opposition party, the Indian National Congress, its candidates and affiliated organisations had to pay 53,776 rupees ($702)— nearly 29 percent more—for the same number of views.

TRC and ad.watch primarily compared the BJP with the Congress because they were the largest spenders on political advertisements. In the 22-month period for which data is available, the BJP and its affiliates spent in total more than 104.1 million rupees ($1.36m) to place advertisements on Facebook through their official pages. In contrast, Congress and its affiliates spent 64.4 million rupees ($841,000).

But going by the higher rate Facebook charged the Congress, it has paid at least 11.7 million rupees ($153,000) more than what it would have paid for the same number of views had its advertisements been priced at the rate given to the BJP.

In Part 2 of this series, TRC and ad.watch showed how Facebook has allowed a large number of ghost and surrogate advertisers to promote the BJP, boosting its visibility and reach in the elections, even as it blocked almost all such advertisers that were promoting the opposition party and its candidates.

If we include the pricing of surrogate advertisements along with the parties’ official accounts, the deal that the BJP got becomes even sweeter. For all advertisers promoting the BJP, Facebook charged an average of 39,552 rupees ($517) for one million views for an ad, but for all advertisers promoting Congress, it charged an average of 52,150 rupees ($681), nearly 32 percent more.

The findings buttress the Supreme Court of India’s fears (PDF) that Facebook’s policies and algorithms threaten electoral politics and democracy.

“Election and voting processes, the very foundation of a democratic government, stand threatened by social media manipulation,” said the Supreme Court last July while rejecting Facebook’s contentions that it is a neutral and blind platform with close to 240 million users. Facebook had appealed to the court to be exempted from appearing before an inquiry committee set up by the Delhi government to probe the 2020 riots in the city and complaints that Facebook had been used as a platform to foment hate.

The court’s order was based on takeaways from controversies and debates in other countries—particularly the US, which was buffeted by revelations that Facebook was used to influence the 2016 presidential election.

Advantage, BJP

TRC and ad.watch found the first of its kind data-backed evidence that Facebook’s pricing algorithms are giving a leg-up to the BJP in election campaigns.

Facebook delivers advertisements, which are posts paid for by political parties or their surrogate advertisers, into the news feed of its users. Unlike traditional print or broadcast media that charge advertisers based on predefined rates, Facebook owner Meta Platforms Inc charges wildly varying prices for advertisements based on real-time auction of Facebook’s news feed and space on its other platforms. The target audience can be defined by the advertisers, but how many times an ad will appear on users’ screens and at what cost is defined by an opaque algorithm.

The algorithm decides the price of an advertisement mainly based on two criteria: how valuable are the eyeballs of the target audience and how “relevant” is the advertisement content to the target audience. Meta does not, however, reveal precise calculations that go into deciding the price for a particular ad.

An analysis by TRC and ad.watch of the money spent on ads and the views they received found that in nine out of 10 elections that they reviewed, the result was the same: a better deal for the BJP.

In response to a list of detailed questions over email, Meta said: “We apply our policies uniformly without regard to anyone’s political positions or party affiliations. The decisions around integrity work or content escalations cannot and are not made unilaterally by just one person; rather, they are inclusive of different views from around the company, a process that is critical to making sure we consider, understand and account for both local and global contexts.”

It did not respond to the specific question on the different prices that its ad platform charged the BJP and other parties. Meta’s full response can be read here (PDF).

In the three-month campaign leading up to national elections in 2019, which coincided with state polls in Odisha, Arunachal Pradesh, Sikkim and Andhra Pradesh, Facebook’s algorithm charged the BJP and its candidates 61,584 rupees ($804) on average for 1 million views of an advertisement, but Congress had to pay 66,250 rupees ($865) for the same number of views.

State elections in Haryana and Jharkhand later that year saw a similar trend in price differences.

In the 2020 Delhi assembly elections campaign, Congress and its candidates paid Facebook 39,909 rupees ($521) on average per million views, but the BJP paid only 35,596 rupees ($465). The Aam Aadmi Party (AAP), the winner of the Delhi elections and another contender to the BJP, was charged the highest at 64,173 rupees ($838) per million views, 80 percent more than what the BJP paid.

And in Bihar assembly elections in 2020, the BJP paid 37,285 rupees ($487) per million views while the Congress shelled out 45,207 rupees ($590) to reach the same number of views. In the same election, Janata Dal United, the BJP’s main regional ally, was charged the highest 66,704 rupees ($871) per million views.

Only in the Maharashtra elections did Congress score a cheaper deal when it paid 38,124 rupees ($498) to the BJP’s 43,482 rupees($568) per million views.

Indian election laws put a cap on the campaign expenditures of candidates to ensure that elections are fought on a level playing field. But Facebook has allowed the BJP and its candidates to consistently reach more people than other parties for every rupee spent. This unfair advantage to the BJP, experts say, undercuts political competition, an important bedrock for the functioning of any electoral democracy.

“Any evidence of significant price distortion in campaign expenses is an appropriate subject for the ECI to investigate and warrants a serious conversation with Mr Nick Clegg [former deputy prime minister of the United Kingdom who now serves as the vice president of Global Affairs and Communications at Meta] and other tech giants,” said Mishi Choudhary, technology lawyer and legal director at the Software Freedom Law Center in New York. “A Model Code of Conduct is only worth anything if it’s enforced impartially irrespective of the ruling party in power,” she said, referring to the set of rules that ECI imposes to regulate election campaigns.

ECI did not respond to TRC’s questions despite repeated reminders. BJP’s chief spokesman Anil Baluni and IT and social media head Amit Malviya too did not respond to TRC’s queries.

How we accessed and analysed data

In Part 2 of the series, we detailed how we accessed advertiser data for the more than 536,000 political ads that were placed on Facebook between February 2019 and November 2020 and grouped them under political heads.

To compare the ad rates charged by Facebook to the BJP and Congress, we calculated the aggregate spend and aggregate views for all advertisements by all advertisers associated with each party for each election. We used these aggregate figures to calculate the cost per million views for each party.

Ad Library does not disclose the exact cost or views of an advertisement. For each ad, it provides the expenditure and views figures in the range of 500s. We used averages of upper and lower limits of those ranges for our calculations. There were a few advertisements in the library that Facebook says got more than 1 million views, and some for which more than 1 million rupees were spent but it didn’t disclose what was the upper limit of those ranges. We excluded all such ads from our calculations.

For the remaining ads, Congress and its candidates spent 52.96 million rupees ($691,520) to get 984.8 million views. But the BJP and its candidates spent just 42.05 million rupees ($549,064) and got a much higher return on its investment – more than 1 billion views for their Facebook ads. We calculated the cost per million views for both parties based on these figures.

A similar analysis of the Ad Library API data accessed by the New York University Ad Observatory for the 2020 elections in the US has shown that Former President Donald Trump’s campaign paid lower advertising rates than President Joe Biden’s.

Laura Edelson, lead researcher at the Ad Observatory project who reviewed the methodology and findings of our investigation, said, “These findings show important disparities in political ad pricing that has serious consequences for the ability of different political parties and candidates to reach voters with their message.” Anyone concerned about the democratic process, she added, should be concerned about these findings, and Facebook should work to ensure their platform can be a level playing field for political speech.

Part 4 of this series will reveal how Facebook’s algorithm, designed to keep users hooked to their newsfeeds, helps India’s BJP cut competition in election campaigns.

Kumar Sambhav is a member of The Reporters’ Collective and Nayantara Ranganathan is a researcher with ad.watch.