Pakistan’s child refugees long for schools

Government accused of doing little for education of about 300,000 displaced due to army offensive in North Waziristan.

Bannu, Pakistan – Nearly four months after hundreds of thousands of people from Pakistan’s North Waziristan were forced to flee their homes in the wake of a military operation, an overwhelming number of children are out of school due to inadequate government arrangements, people and activists have said.

According to the Federal Disaster Management Authority (FDMA), nearly 700,000 Internally Displaced People (IDPs), including approximately 300,000 children, have settled in North Waziristan’s neighbouring districts. The majority are in Bannu, with lesser numbers in Dera Ismail Khan, Karak and Lakki Marwat districts.

Keep reading

list of 4 items‘Triple spending’: Zimbabweans bear cost of changing to new ZiG currency

‘We share with rats’: Neglect, empty promises for S African hostel-dwellers

Thirty years waiting for a house: South Africa’s ‘backyard’ dwellers

I felt they did not want to teach us. They only make these 'arrangements' in name, they don't practically mean it.

Of those children, however, only about five percent have been able to enrol in public, private or NGO-run schools, according to UNICEF.

“I came to Bannu by foot on June 18. There are about 12 of us in my family,” said Salman Shah, 20, a native of the town of Miranshah.

“When things got bad there, we knew that this would be a long operation. We knew that we would have to continue our education somewhere else,” said Shah, who was pursuing a Bachelor’s degree in political science from the Miranshah government college.

Pakistan’s army launched Operation Zarb-e-Azb , an aerial and ground forces operation targeting Tehreek-e-Taliban Pakistan (TTP) and their allies in the tribal region bordering Afghanistan back in June . Since then, it claims to have killed more than 1,165 “terrorists” and made major gains, denying the TTP and other groups space to operate in an area that they had virtually taken over since 2007.

Shah, along with fellow students from his home college, has been seeking to get admission at Bannu’s postgraduate degree college but procedural difficulties have gotten in the way.

Inadequate facilities

Students and staff from Miranshah government college were promised that they would be accommodated in the new college or given separate classes, but Shah and several other students said that the government was providing facilities only on paper.

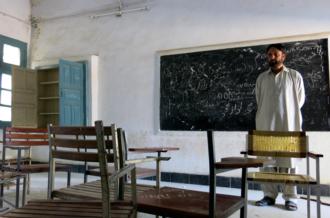

Classrooms at the postgraduate college, for example, were empty, even though teachers were available.

“We had to figure everything out on our own … the facilities are OK, but they are not telling us where to go and what to do to access them,” Shah told Al Jazeera.

Muhammad Sultan, the principal of Miranshah College, said that the fact that the IDPs have been scattered across various districts makes it difficult for them to attend classes at a single location.

|

| Muhammad Sultan, the principal of Miranshah College, says students are unable to attend the replacement classes provided by the government [Asad Hashim/Al Jazeera] |

Sultan, who has continued to teach here in Bannu, said that of the 950 students from his institution, none were attending classes since becoming IDPs.

The situation is barely any different at public primary and secondary schools, where the government has promised to accommodate IDPs.

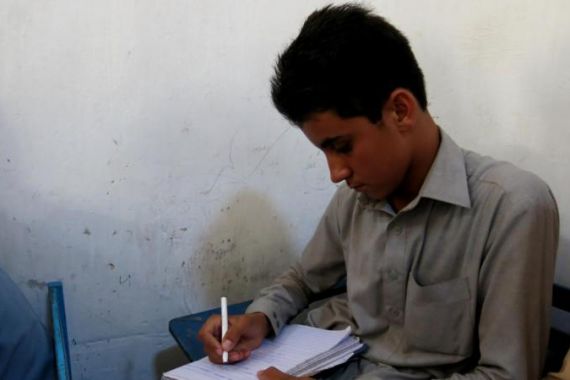

“We went to the government school, but they did not make space for us. I felt they did not want to teach us. They only make these ‘arrangements’ in name, they don’t practically mean it,” said Shafiq Rehman, 14, a student from the town of Mir Ali.

For their part, government school administrators said that schools in Bannu, an underdeveloped backwater of Khyber-Pakhtunkhwa province, were already stretched beyond capacity.

“We have had to remove benches and desks to make room for our students to be able to sit on floor mats in our classrooms,” said Jahanzeb Khan, an administrator at one of Bannu’s largest public high schools, which has accommodated 65 IDP students in its classes.

He admitted, however, that it appeared that the government’s education department, to which he belongs, was “indifferent” to the plight of the IDPs, and that any arrangements that were being made were happening at the discretion of individual school administrators.

Volunteer organisations

Several NGOs and private schools have stepped in to try and make up that gap.

The Bacha Khan Free Education Centre (BKFEC), for example, was founded by a dozen Bannu natives in September, with an aim to providing free classes to IDP children.

“When they first came, their attitude was very scared and nervous,” said BKFEC administrator Muhammad Ishaq, of the IDPs who sought admission. “They didn’t know anything about their future. They didn’t know if they would get admission or find a school here.”

Rehman, a ninth grade student at the school, said he was happy there.

“The classrooms are small, and the chairs are also very small, but we are very satisfied here. Because they teach us properly, and they treat us well. I see my future as very bright if I continue here,” he told Al Jazeera.

In total, UNICEF says that only about 15,000 IDP children are currently enrolled in private, government and NGO schools – a drop in the ocean of their actual numbers, which are in the hundreds of thousands.

“The government is not really helping. It is their duty to [help], because these are our students, they are citizens of this country,” says Ali Rehman, 39, a volunteer teacher at BKFEC.

|

| Students at the Bacha Khan Free Education Centre, a volunteer-run free school, are crammed into tiny classrooms, as the administration cannot afford bigger buildings [Asad Hashim/Al Jazeera] |

UNICEF, working through partner organisation Basic Education For Afghan Refugees (BEFARe) in Bannu, is targeting children between the ages of four and 12, in order to provide both schooling and psycho-social support.

“I observed that the IDP children were a little bit frightened, a bit panicked, by the environment [and trauma of leaving home],” said Ziauddin Afridi, BEFARe’s coordinator in Bannu, adding that many of the children he had met in makeshift IDP camps across the district appeared to be traumatised.

“In Waziristan, the ammunition that the army has used, the shelling, has affected everyone: children, parents and even livestock. All were disturbed…,” he told Al Jazeera, adding that those children who had so far enrolled in BEFARe’s 44 schools had begun to show modest improvements.

The lack of educational facilities at the camps is not surprising given the low literacy rates in Pakistan ( hovering at about 55 percent ), but the situation is particularly acute in North Waziristan, where that number drops to just 15.7 percent . That trend is mirrored across federally administered tribal regions, with the area consistently lagging far behind the rest of Pakistan on basic socioeconomic indicators .

“Things were difficult there, because of the violence,” said Shah, the BA student from Miranshah, adding that he and other students often missed classes due to curfews or Taliban attacks.

Q&A: Pakistan’s children traumatised by war

Meanwhile, tribal elders said the military had provided no timeframe for the IDPs’ return.

Addressing a press conference in Bannu on Friday, a tribal jirga representing the IDPs demanded that they be told when they could return, but also that the government make major changes the way it administers and caters to the area.

“Our biggest demand is that we need a timeframe for when we can go back to our area,” Malik Ghulam Khan Wazir, a community leader from Dattakhel, in North Waziristan, told Al Jazeera after the press conference. “We will only go back to a peaceful Waziristan, where the government fulfils its responsibilities. We don’t have roads, schools, hospitals, and we don’t have jobs.”

As for the students in Bannu, they are still running from pillar to post to try and find a way to continue their studies.

“The government has abandoned [us]. If I want to continue my education, I have to do it on my own. The government should also do something. You cannot clap with just one hand,” Shah said.

Follow Asad Hashim on Twitter: @AsadHashim