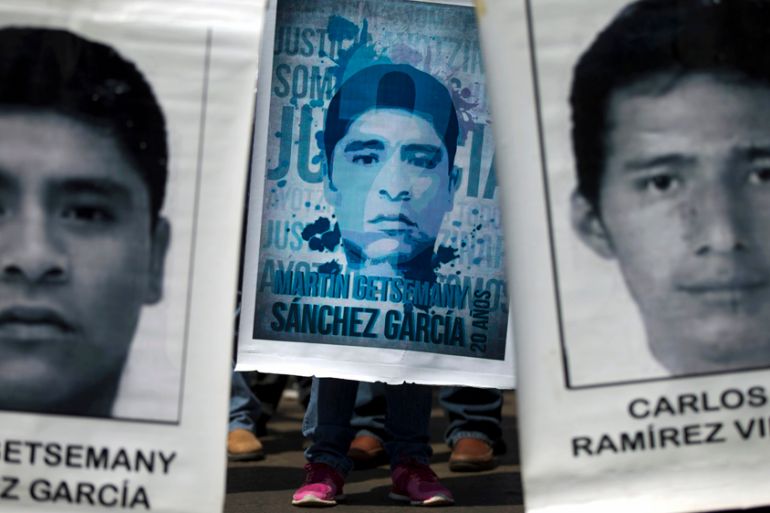

Mexico: Demanding the return of 43 missing students

Eight months later, friends and family of the disappeared are in the US to keep the fight to find the Mexicans going.

San Ysidro, United States – Blanca Luz Nava Vélez stood at a church in California, just across the border from Mexico, the hills of Tijuana twinkling in the dusk a few kilometres away.

She said she has not rested since her son was taken.

Keep reading

list of 4 itemsBurkina Faso says HRW massacre accusations ‘baseless’

Iraq criminalises same-sex relationships with maximum 15 years in prison

The Abu Ghraib abuse scandal 20 years on: What redress for victims?

“We’ve been fighting to bring back our children, day after day,” Vélez told Al Jazeera, blinking away tears.

Her son, Jorge, is one of the 43 Mexican students who went missing last September.

At first, Vélez joined families to search for him and his classmates in and around Iguala, where gunmen shot and killed six people before pushing the students into vans.

![Angel de la Cruz and Blanca Luz Nava Vélez [Brooke Binkowski/Al Jazeera]](/wp-content/uploads/2015/05/d0f60ea88dc44ef9878374ac5b8d2309_18.jpeg)

Now Vélez is travelling through the United States as part of a delegation from Mexico called the Caravana 43.

It’s part of a series of high-profile trips to the US and through Europe to bring international attention to the case of the missing Ayotzinapa students.

“I hope that President [Barack] Obama will receive us, and that we can speak with him and ask him to demand that the Mexican government returns our sons to us,” she said.

Ángel Neri de la Cruz Ayala – a baby-faced 19-year-old Ayotzinapa student who survived the night of September 26, 2014 – is also part of the delegation.

“I’m here to ask the United States to help us,” de la Cruz told Al Jazeera. “We want the US to pressure Mexico’s government to bring back my 43 classmates.”

The Caravana 43 is also asking the US to end the Merida Initiative, which earmarked billions of dollars to modernise Mexico’s security forces.

Members of Caravana 43 say American-trained Mexican forces, using equipment bought with Merida money, are killing Mexican citizens instead of protecting them.

There’s also pressure for change coming from similar delegations within Mexico. A few kilometres south and a few weeks earlier in Tijuana, Mexico, Ayotzinapa students Uriel Alonso Solís and Gamaliel Cruz wended through its downtown, holding a sign depicting the faces of their 43 vanished classmates.

“Fue el estado!” they chanted. “It was the state!”

Fue el estado is a rallying cry for Mexicans aghast at the stories of disappearances and mass graves that have been emerging from all over the country – many of which are alleged to happen at the hands of Mexico’s police and military.

Repeated requests for comment from Mexican officials were not answered.

Our government took our children alive, we want them returned alive.

Students say forced disappearances and massacres have been common in poverty-stricken, heavily indigenous areas.

Protesting is as much part of their schooling as teaching. Demonstrations are rowdy, sometimes militant, and occasionally deliberately shocking: Students at the chronically underfunded schools set up roadblocks to extort money for their schools from people driving through.

Since they also lack school transportation, students will sometimes appropriate city buses, paying off drivers to drive them in convoys to fundraisers and school conferences.

It was one such convoy that police intercepted in Iguala last September. The mayor of Iguala, José Luis Abarca Velázquez, reportedly feared they would disrupt a fundraiser his wife was holding, and so Abarca ordered police to “confront” the students.

Solís said police showed up and started lobbing tear gas and firing guns at them. Six people were killed, including a pregnant woman riding in a nearby taxi.

He hid and watched his classmates being loaded into vans at gunpoint by masked men.

It was the last time any Ayotzinapa students saw their classmates, and since then Solís and supporters say Mexico’s government has spun a web of lies and misdirection about their whereabouts.

“They stated a bunch of things,” Solís told Al Jazeera. “First, they told us that the police had turned over our companeros to the organised crime group Guerreros Unidos, and that Guerreros Unidos killed them and buried them in clandestine pits.

“Later they told us that Guerreros Unidos dismembered them and placed them in black bags and threw them into the river… Now they are saying that our companeros were part of organised crime, and that is why they burned them all that night.”

Solís said every story they have heard so far is a fabrication.

“Our objective now is finding our 43 classmates alive, finding justice for our fallen classmates, and receiving compensation for damages,” Solís said.

Eight months on, many of the Ayotzinapa students who survived the shoot-out and mass kidnapping are still touring around Mexico and the US.

They all have the same goal: to keep Ayotzinapa in the news to drum up national and international support for an investigation into the deaths and disappearances of their classmates.

The students also directly blame Mexico’s police, military, and government for the deaths and disappearances, and believe their missing classmates are still alive and want them returned safely.

They are also asking Mexicans to boycott the upcoming legislative elections in June, saying Mexico’s political system is too corrupt to continue. If people don’t come out to vote, they say it will send elected officials a strong message.

![Uriel Alonso Solís [Brooke Binkowski/Al Jazeera]](/wp-content/uploads/2015/05/c42d39bd8cb647a4bec705058cf3ea4c_18.jpeg)

Since September, protests over the Ayotzinapa 43 have flared throughout Mexico, fed by a botched investigation and accusations of government cover-ups.

Citizen-led search and forensics groups in Iguala have turned up dozens of mass graves, both fresh and old, but none have yet contained the bodies of the students. The unrest has created a political shake-up.

The mayor of Iguala and his wife fled and were later jailed. The governor of Guerrero state resigned and Mexico’s attorney general Jesús Murillo Karam – harshly criticised for the way he handled the Ayotzinapa case – has been reassigned.

Parents of the missing students appealed to the United Nations for an investigation, which considered the issue of enforced disappearances at a special session in early February.

It recommended reparations for the families, and concluded that Mexico’s lack of transparency around the issue of missing people in general is major cause for concern.

“There are no firm figures for the victims of enforced disappearance, and how many people are missing,” Luciano Hazan, a member of the UN Committee on Enforced Disappearances, said in an email to Al Jazeera.

“That is why one of the recommendations we are making to the Mexican state is the establishment of a single national register to allow victims and the wider Mexican society to know how many disappeared persons there are, how many have been disappeared by organised crime, and how many have been disappeared by forces of the state.”

|

|

| Often-criticised Mexican police give their side of the story |

An interdisciplinary group of experts designated by the Inter-American Commission on Human Rights arrived in Mexico in March to begin its own investigation into what happened to the Ayotzinapa students and look into whether any criminal charges should be filed, and if so, against whom.

The commission said Mexico needs to reinstate its suspended search for the missing students.

Meanwhile, Cruz said he and his classmates will continue to demand transparency and justice from the Mexican government.

“This struggle is not only about Ayotzinapa,” Cruz told Al Jazeera. “It’s not only about the 43 people who disappeared, but probably thousands around the country. We will continue to demand justice and life with dignity.”

Blanca Luz Nava Vélez also vowed not to give up on finding her son.

“Our government took our children alive, we want them returned alive,” said Vélez.