Remembering China’s Cultural Revolution

Some historians say the number of dead could be as high as two million people during Mao Zedong’s communist purge.

You would be hard pressed to find someone in China who has family, friends or relatives who were not touched in some way by the Cultural Revolution.

The father of China’s President Xi Jinping was persecuted and the young Xi was forced into hiding in the countryside.

It was a mass brainwashing – collective madness in which those with the most sadistic streaks flourished – and many did.

No wonder so few people are prepared to really talk about what happened; to admit their guilt, to express their sorrow. It is as if one is trying to talk to Cambodians about life under the Khmer Rouge.

There are still no official figures on how many people were killed or purged in China during the Cultural Revolution.

But some historians say the number of dead could be as high as two million – still less than the millions who died during the famines blamed on Chairman Mao’s disastrous policies in the late 1950s.

READ MORE: China’s Cultural Revolution must be confronted

For many Chinese people, the Cultural Revolution remains a taboo subject, especially among those of 65 years of age or older. But occasionally – just occasionally – you come across someone who is prepared to confess to the very worst of crimes.

For the past three decades Wang Yiju has run a successful riding school and stud farm outside Beijing. But it is his life in the previous two decades that he has agreed to discuss on this bright spring day.

In clinical dispassionate language he describes how he became sucked into the anarchy going on all around him.

“At first we were reluctant to beat others, but someone would criticise us … Finally we loved to beat others. Killing became very common at the time when people treated fighting as fun. It was natural to kill people in such circumstances,” said Wang.

On August 5, 1967, Wang became a killer. His victim was another student from a rival faction.

“I beat the back of his head with a rod. The rod was thick and hard, very long about 1.6 metres long, similar to the handle of a big hoe … I beat his head and broke the back of his skull. The police later told me that one blow was enough to kill a person with such a rod and with my power.”

Wang was arrested, but later freed after the family of the dead student forgave him.

He finally made a full apology in 2008 and is urging others who killed to confess.

“Few people will understand what the Cultural Revolution was if we all hold back the truth,” said Wang. “I think the true nature of that time is made up of memories and stories of the participants who clearly know what happened. Someone has to tell the truth, or our generation will have failed. That is why I spoke out.”

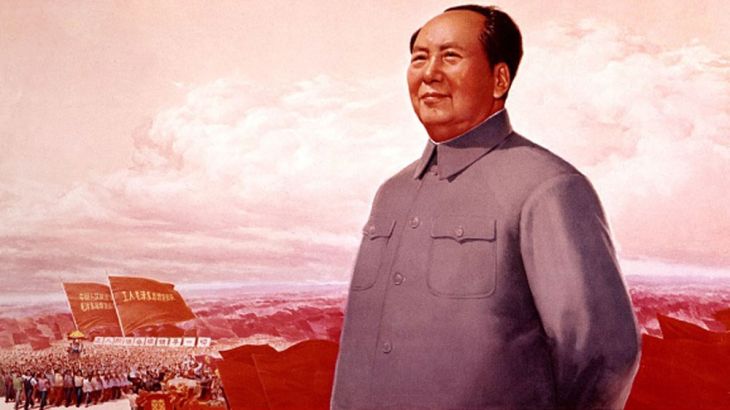

It is a paradox that Mao Zedong, the man who unleashed the Cultural Revolution, remains the most enduring political brand in China.

His face is ubiquitous. It’s on banknotes, T-shirts, caps, key rings and he adorns millions of commemorative plates. Mao’s portrait still hangs over the entrance to the Forbidden City facing Tiananmen Square.

READ MORE: China’s ‘red princess’ turned investigative journalist

During the 1989 student protests, which happened only 13 years after the Cultural Revolution came to an end, the Forbidden City was repeatedly vandalised.

For the moment, Mao’s image has yet to be eclipsed by another. But more often these days you do see another face appearing beside Mao’s, that of China’s current President Xi Jinping.

That is a sign, some Western commentators say, that Xi is building a personality cult with echoes of Mao.

|

|

| Cult-like following for China’s president grows |

.