Roma Holocaust: Amid rising hate, ‘forgotten’ victims remembered

New London exhibition includes harrowing Nazi directives and testimony from persecuted Roma and Sinti minorities.

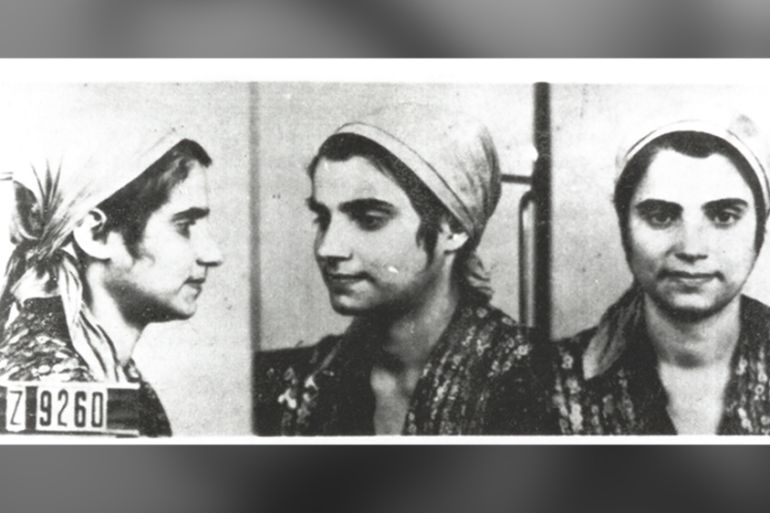

London, United Kingdom – Margarethe Kraus was just a teenager in 1943 when she was deported from her home in Czechoslovakia to Auschwitz.

While imprisoned in the concentration camp, she endured extreme maltreatment and was subject to medical experiments.

Keep reading

list of 4 itemsDenmark’s tough laws on begging hit Roma women with few other options

Another Roma boy dies in police chase, marking grim pattern in Greece

‘My father didn’t beat my mother in a gypsy fashion-he just beat her’

She survived the Holocaust. Her parents did not.

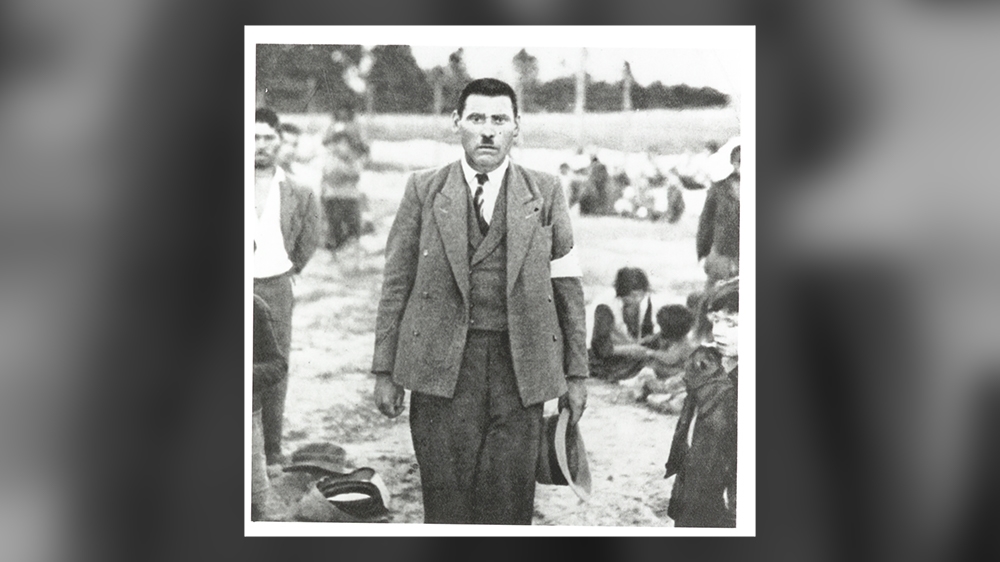

They were among the 250,000 to 500,000 Roma and Sinti people – between 25 and 50 percent of the minority’s entire population in Europe at the time – murdered by Nazis and their collaborators during the second world war.

Kraus’s story features in a new exhibition at London’s Wiener Holocaust Library.

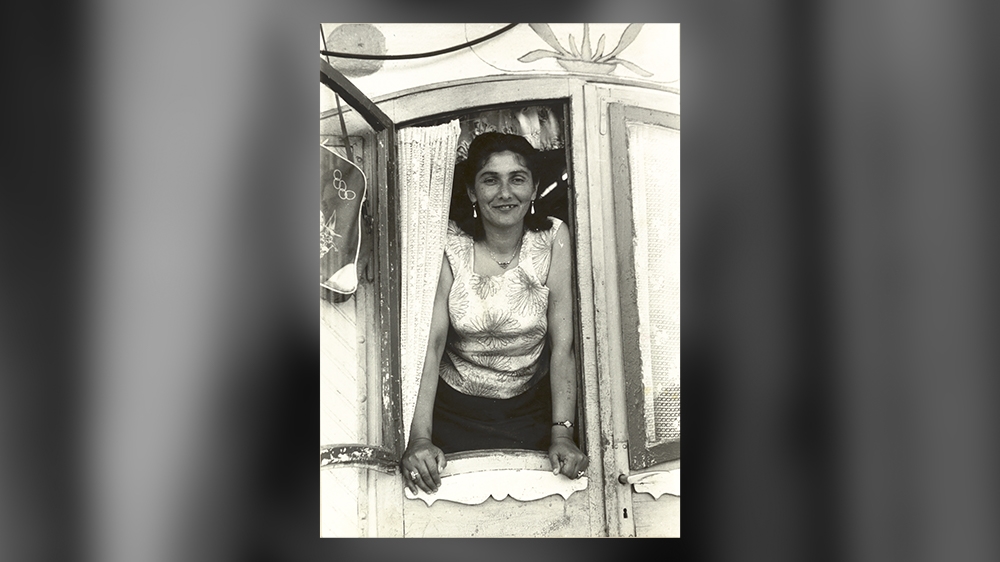

The exhibition, Forgotten Victims: The Genocide of the Roma and Sinti, seeks to uncover this often-ignored aspect of the second world war. It examines the persecution of Roma people in Europe in the years leading up to the war, genocidal policies towards them during Nazi rule, and the community’s ongoing struggle for recognition and restitution.

“Even if people are aware that the Nazis targeted Roma as well as Jews, it isn’t necessarily a subject that people know that much about,” said Barbara Warnock, the curator of the exhibition.

“The genocide that occurred against Roma across Europe was a comparable policy to that against the Jewish community, but it was more piecemeal, less systematically pursued.”

The exhibition contains a variety of archive materials, including testimony from Roma and Sinti survivors and other witnesses, and records from the International Tracing Service, which was set up for families to look for missing relatives during and after the war.

The details are horrifying. In testimony given after the war, a Jewish Holocaust survivor outlines the “liquidation” of the Gypsy camp at Auschwitz in August 1944, when all the prisoners there were gassed.

A Roma woman who features in the exhibition gives an account of the sexual violence she endured.

“Many groups were targeted [by the Nazis], but Jews and Roma were the only two people who were targeted under the final solution for protecting German racial purity,” said Jonathan Lee, communications coordinator at the European Roma Rights Centre.

“That was not recognised for a very long time. In fact, what most historians and therefore governments and politicians would do, is refer to genocide of Roma using Nazi terminology. They would say that Roma were put into camps for being ‘work-shy’, for being ‘asocial’, for being ‘thieves’.”

This reflects contemporary stereotypes and prejudices against Roma people.

A 2012 report by the European Council’s commissioner for human rights found that “Roma have been collectively stigmatised as criminals”. Among other measures to address this scapegoating, the report recommended that “past atrocities against the Roma should be included in history lessons in schools”.

Framing the persecution of Roma and Sinti people during the second world war as being primarily due to their antisocial behaviour had a serious material impact.

“In the initial post-second world war period and into the 1950s, restitution was often blocked to them on the spurious basis that they hadn’t been incarcerated for racial reasons, but because they were criminals,” said Warnock, the curator. “That was a massive problem in terms of getting recognition and restitution.”

Recognition has been slow.

At the Nuremberg trials, crimes against Roma people were not specifically prosecuted.

It was decades after the war, in 1982, that Germany acknowledged there had been a genocide against the Roma. In 2011, Poland officially adopted August 2 as a day of commemoration for the Romani genocide.

“There are a number of different reasons for this. One is simply prejudice against us, and ignorance about our history,” said Ian Hancock, a Romani scholar and advocate and professor emeritus at the University of Texas at Austin.

Another reason is less obvious.

“There have been many books, not exclusively but mostly by Jewish authors, about the Holocaust and the fate of the Jews,” Hancock said.

“In the Romani case, there was limited literacy. We have a nomadic tradition and an oral history tradition. We just were not equipped – and to a large extent are still not equipped – to do the scholarship or to write books.”

This lack of recognition has had a severe effect on survivors of the Holocaust and their descendants, most of whom did not receive any compensation.

As a point of comparison, since 1952, the German government has paid over 71 billion euros ($79bn) in pensions and social welfare payments to Jewish people who suffered under the Nazi regime.

The legacy of the Holocaust has been wider anti-Gypsyism across Europe. We never really had this taboo moment where anti-Gypsy rhetoric was no longer allowed.

But the lack of recognition of Roma and Sinti suffering has had a more broad-ranging effect.

“The legacy of the Holocaust has been wider anti-Gypsyism across Europe,” said Lee. “We never really had this taboo moment where anti-Gypsy rhetoric was no longer allowed.”

The Roma are Europe’s largest ethnic minority, with up to 12 million living across the continent, mostly in Central and Eastern Europe. Their life expectancy is 10 years less than other Europeans.

In a 2016 survey, one in four Roma said they had experienced discrimination in the last year.

As far-right populist movements sweep across the continent, anti-Roma rhetoric is ramping up.

In June 2018, Italy‘s then-Deputy Prime Minister Matteo Salvini called for an “answer to the Roma problem” and said: “Unfortunately we will have to keep the Italian Roma because we can’t expel them.”

Earlier this year in Bulgaria, Defence Minister and Deputy Prime Minister Krasimir Karakachanov proposed a controversial package of policies for, in his words, “dealing with the Gypsy question”. These proposals include free abortions for Romani women.

“Certain chains of events are happening, particularly in Eastern European countries, that should be warning signs as to what could happen,” said Lee. “But that recognition doesn’t really exist because it’s to do with Roma, and the nature of the genocide has always been denied.”

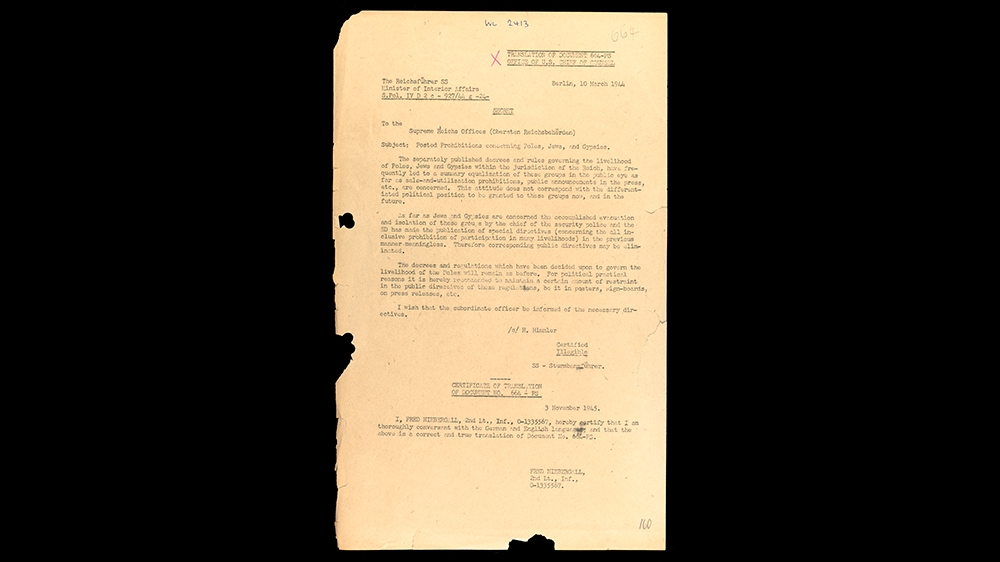

One of the documents in the Wiener Holocaust Library’s exhibition is a directive written by Heinrich Himmler, head of the SS, in March 1944.

The letter is written in a bureaucratic tone that belies the horror of its contents.

In it, Himmler states that “the accomplished evacuation and isolation” of Jews and Gypsies means that directives against them are no longer necessary. This means that the vast majority of Jews, Roma and Sinti in greater Germany had already been murdered or deported to ghettos and camps. It is a chilling reminder of what can happen.

Recognition of what took place during the war is an important step, but there is more to be done.

“We still have not been able to get compensation for what was taken from us,” said Hancock. “It is a very clear, ongoing example of deliberate exclusion. The argument that we simply didn’t know can no longer be maintained, because people do know now – if they bothered to look.”