Anger simmers in Varanasi over plans to modernise ancient city

To the dismay of residents and activists, India’s centre of Hindu culture on the Ganges’s shores is rapidly changing.

Varanasi, Uttar Pradesh, India – The narrow alleyways winding down along pale buildings and maharaja’s “havelis” or king’s palaces are the pride of the old city’s residents.

Decrepit yet stately buildings scratched by time and elements, crammed side by side on stratification of different ages, are the defining marks of Varanasi, in northern India.

Today, they are at the centre of a controversy gradually attracting attention in the national media.

Considered the centre of Hindu spirituality and the most auspicious place to die, the city of Lord Shiva and its old centre on the western shores of the sacred Ganges River are changing as government-sponsored contractors demolish buildings, often knocking down small, old temples.

“The project has started without a plan, they [the government] have power and money, hence have begun the demolition without a roadmap,” said Trilochan Shastri, chief priest at the Tulsi Manas Temple.

Shastri has opposed the regeneration project since its inception.

“Temples … are all over Kashi,” he said, using another name for Varanasi, “underground, near the drains, inside the houses, we can hardly count them.”

The government has acquired 300 properties to make way for a 400-metre long and 15-metre wide path leading from the city’s main pilgrimage site Kashi Vishwanath Temple, known as Golden Temple, to the holy Ganga River.

Our culture and our history make us oppose this corporatisation model: why do we have to look like Kyoto?

There are plans to raze down all the buildings on the path: a jigsaw puzzle of multi storey houses belonging to different ages across an area of 25,000 square-metres.

The temple and its sacred statue, are nestled in the heart of Varanasi’s old town in a muddle of tortuous lanes.

Along with Varanasi’s imposing ghats, the temple is a city trademark.

On religious festivities, hundreds of thousands of pilgrims queue up for hours to visit the place of worship along the bamboo barricades set up to channel the crowd.

Officials say the area needs to be cleared to provide visitors with more amenities.

The project comprises a corridor leading to the Ganges– part of a modernisation and beautification drive led by the Varanasi administration, which also happens to be Modi’s constituency in the 2014 elections and his flagship project – and has stirred anger and opposition from different sides.

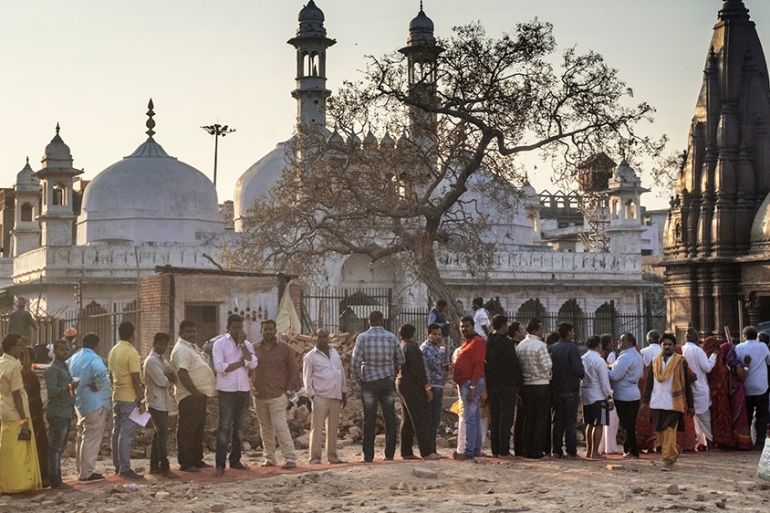

![The area of the old city surrounding the Kashi-Vishwanath Temple is full of dust and rubble as contractors demolish buildings in the way [Andrea de Franciscis/Al Jazeera]](/wp-content/uploads/2019/03/83de1312573d40798b6dd8e301a47563_18.jpeg)

“Since Narendra Modi came to power, he decided to change things in Varanasi: a new development model inspired by Gujarat (where Modi was chief minister) has been forced upon us,” said Jagriti Rahi, an activist monitoring the demolitions. “Our culture and our history make us oppose this corporatisation model: why do we have to look like Kyoto?” he added, referring to a city often cited by Modi as a model.

So far 165 structures, 95 residential buildings and 55 temples and places of worship have been acquired, of which 43 were incorporated by successive buildings.

“The government has allocated 6 billion rupees (almost $85bn) for the project, a sixth of which will go for compensations,” said Rahi.

Residents have said they were not consulted and there was no formal disclosure of the project.

“The protests started when the project began, a year ago. A year in which the city has changed its face. Our heritage is being destroyed,” said journalist Suresh P Singh, as he pointed to a finely carved, marble palace about to be brought down.

“Initially, they spoke of resettlement, but no one has been resettled yet while [significant sums are] being spent on mindless acquisitions.”

“Compensation in cash is being paid to residents who lived there for generations, regardless of their status of being owners or occupiers, also in case of disputed properties,” he said, claiming that various strategies have been employed to move residents from their homes.

![A Hindu temple amidst the debris of old buildings in the area of Pakka Mahal. Civil society groups and also Hindu clerics have protested against the government-driven demolitions [Andrea de Franciscis/Al Jazeera]](/wp-content/uploads/2019/03/f2b00fd29d824f469d095d14a7b13581_18.jpeg)

By now, 80 percent of the demolition has been completed.

The streets are congested with dust and rubble and overloaded donkeys take the debris away.

Even the sections of society that are traditionally supportive of the ruling Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP) have opposed the project, including Hindu religious leaders who say that small temples and idols have been destroyed.

Civil society groups and the head of the Anjuman Intazamiya Masjid (Aim), the trust managing the Gyanvapi Mosque which lays inside the Golden Temple perimeter, have filed a petition in the Uttar Pradesh High Court to end the project.

Another petition to safeguard the Gyanvapi Mosque was filed in the Supreme Court – both were rejected.

![Contractors are seen demolishing houses to make way for the newly planned Kashi-Vishwanath Corridor, leading from the temple to the Ganges River [Andrea de Franciscis/Al Jazeera]](/wp-content/uploads/2019/03/0163d7373386414f978f70966c615b1f_18.jpeg)

Thousands of residents and members of the Muslim community gathered to protest when a devotional platform leading to the mosque was demolished last October. It was rebuilt shortly after.

“They feared the platform was the prelude of an action against the mosque. The project is hidden, people just want the mosque to be safe,” said Haji Ahmed Ishtiyaque, member of the Aim. “The government is pushing a communal agenda, but not all Hindus support Hindu ethnonationalism, India is a secular country.”

Officials reject claims that their initiative is destroying an ancient city.

“There is no blueprint as such, it’s in the process of making,” said Vishal Singh, head of the trust managing the Vishwanath temple.

“The idea is to provide a clean place and space for people visiting here in their spiritual quest, to make it a world-class place.”

“None of the temples have been destroyed, never, in fact, we’re bringing them out and restoring them.”

He argued that opposition was politicised and lacked credibility.

“Whatever you do people are bound to oppose it, it’s just mere resistance to change,” he said. “We’re restoring the city’s pristine glory.”

![A woman visits a temple recently surfaced from the rubble. Some 55 temples and places of worship have been found in the area acquired by the government [Andrea de Franciscis/Al Jazeera]](/wp-content/uploads/2019/03/e8eff5ab40f74aed84384eaea0a2d5c9_18.jpeg)