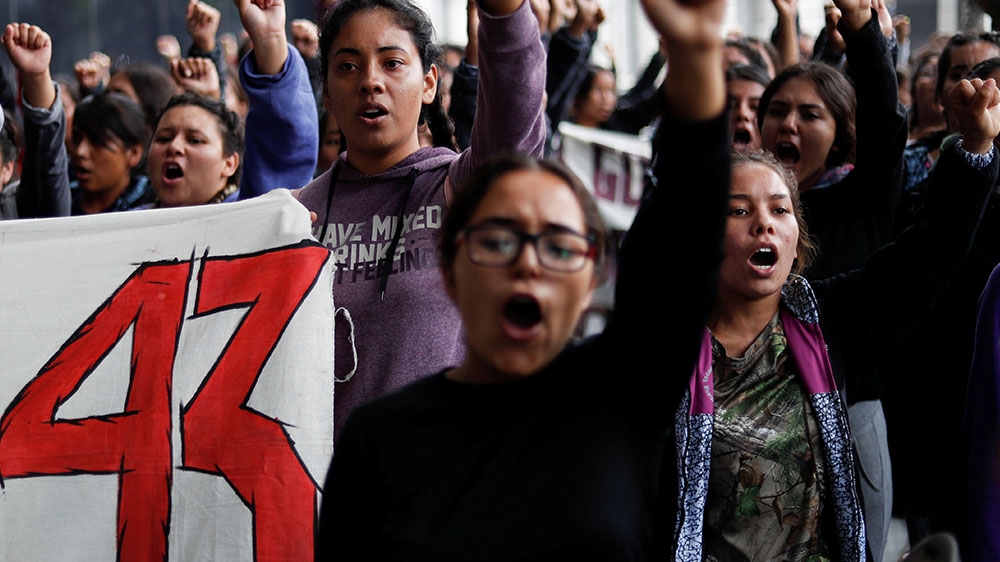

Case of 43 Ayotzinapa missing students unresolved five years on

Families, friends and rights groups demand more government action in finding 43 students who disappeared five years ago.

Mexico City – There were puddles of blood. That is according to Marco Cruz Flores who remembers clearly the night of September 26, 2014.

“When we heard Aldo was shot, we decided we’d rush [from Ayotzinapa Rural College for Teachers in the state of Guerrero] to Iguala and go help our classmates,” he said, recalling the day that has haunted many in Mexico for five years.

Keep reading

list of 4 itemsEcuador spat: Trotsky to the shah, Mexico’s long history as home to exiles

Mandela’s world: A photographic retrospective of apartheid South Africa

‘Profoundly unjust’: Reactions to court overturning Weinstein’s conviction

“We needed to go get gas first,” Cruz told Al Jazeera. “We could see the lighting in the distance announcing an upcoming thunderstorm. I knew it would be a heavy night.”

By the time Cruz and his friends arrived in Iguala, 120km from the Ayotzinapa rural school and caught up one of two groups of classmates who had commandeered three buses, they found seats “pierced with bullet holes” and “puddles – puddles – of blood”.

Cruz was a third-year student, 21 at the time, but most of the students present were freshmen.

“Many were crying, and we were trying to comfort them,” Cruz recalled.

Aldo Gutierrez Solano, the classmate who was shot in the head, was lying on the ground.

After reporters came to the scene, a group of what Cruz said looked like civilians and police forces opened fire on them again. It was a long night and Cruz managed to escape alive. Three of his classmates were killed – one with visible signs of torture – and dozens of others were wounded, he said.

Another 43 students who had been detained by police mysteriously disappeared, and five years later the search for them – or their remains – continue.

Investigation riddled with irregularities

According to the students’ accounts collected by the Interdisciplinary Group of Independent Experts (GIEI), it was a yearly – and tolerated – tradition for teacher college students from across the country to take over intercity buses along with their drivers to head together in caravans for important rallies and protests.

That night, the students claim they were in Iguala to commandeer more buses to travel the next week to Mexico City for a yearly rally that commemorated the 1968 mass killing of students.

According to one GIEI report issued in 2016 and other independent expert accounts, the buses were intercepted by multiple security forces at two different road points, since the groups had split in different directions.

Security forces opened fire at four of the buses and took 43 students into custody. Students on a fifth bus were unharmed and all of its students set free, according to the expert group reports.

“The next morning, since we were told our classmates had been taken under municipal police’s custody, our parents came to pick us up in Iguala, and we went to their headquarters to bail them out,” Cruz says.

“‘Nope, not here!’ they told us at the police station. We went to every police station and got the same answer. Where did they take them? We still don’t know.”

A few months after the incident, then-President Enrique Pena Nieto’s administration effectively closed the case after procuring confessions from local drug gang members who said they burned all 43 bodies in a dumpster after being instructed by the police to murder the students.

But teams of international experts have disputed that account after identifying multiple irregularities with the case, including confessions obtained by torture, illegal arrests of key suspects and lack of physical evidence to sustain the prosecution’s arguments.

Seeking to make good on his campaign promise, President Andres Manuel Lopez Obrador reopened the case nearly a year ago and designated a special commission to handle the investigations. Seventy-seven of the 142 arrested by previous investigations, have been since released due to case irregularities. No one has been convicted.

“This confirms what we’ve been saying all along,” said Erika Guevara Rosas, Americas Director at Amnesty International.

“The investigations made during Pena Nieto’s administration were plagued with irregularities and cover-ups, possibly for international crimes against humanity involving torture of suspects and forced disappearance of the students,” she told Al Jazeera.

As for the new investigations, “We’ve seen positive progress, there’s now political will to solve the case,” said Guevara, “but things are moving rather slowly and we’re yet to see any new findings.”

Anabel Hernandez, an investigative journalist who has written extensively about what may have happened, said that night saw a huge government operation.

In her book A Massacre in Mexico: The True Story Behind the Missing 43 Students, she claimed the students were unaware that the fifth bus they took was carrying a hidden cargo of at least two million dollars worth of heroin to be shipped to the United States. Independent experts have also suggested such a conclusion.

“It is outrageous that things that should have been investigated five years ago are still not being investigated,” Hernandez told Al Jazeera. She considers the new commission “has not been acting efficiently”.

“The problem is there are public officials that were implicated [in the cover-ups] are still working in the government,” says Hernandez. “The federal police officers I accused of torture in my research are still active.”

Mexico’s Attorney General’s Office and the Office of Mexico’s Sub-Secretary for Human Rights in charge of the new investigation commission declined Al Jazeera’s interview requests.

‘Hope dies last’

On Thursday, officials said that investigators have found the remains of nearly 200 people, but none of the missing students.

Two years after his classmates disappeared, Cruz graduated from Ayotzinapa teachers’ school and today, he is a teacher at a public elementary school.

I know solving a case like this is not like curing a disease from one day to another, it will take time. But hope dies last, and we will be out on the streets until we know where they are.

However, “You can’t just go on about with normal life knowing that your classmates are still missing,” he says, even as five years have gone by since that night.

“I know solving a case like this is not like curing a disease from one day to another, it will take time. But hope dies last, and we will be out on the streets until we know where they are,” says Cruz.