A mother’s death, a childhood without her and a mysterious plant

When a plant arrives after her mother’s death, a girl finds in it the parent who never had the chance to care for her.

My mother dies on April 20. It is a Wednesday wedged between Easter and my eighth birthday. We receive the news as I wrestle with my brother in the living room, on a rug the colour of regurgitated peas. The couches, green velour, are off limits. We are not allowed to sit on them unless invited. In our home, comfort is reserved for adults. The rug belongs to us. We have spent so much time on it watching television that we have waffle-fry scars etched into our elbows.

The night we find out about my mother begins in the same way that every night does. Gramps watches the news while he smokes a Pall Mall and drinks a honey-coloured liquid that smells like some rotten version of the medicine we take for colds. He lowers the upper right corner of the paper to glance at Walter Cronkite, a stern-faced man who seems to deliver nothing but bad news. There is a crisis somewhere with someone over something. Dead bodies hide under white sheets in a conflicted land we only see on TV. When I try to pronounce the name of it, it gets caught on my tongue and rolls out of my mouth wrong. Goaded into playing a game of Connect Four with my brother, I notice him cheating and quit before he has a chance to win.

My grandmother pays bills in the kitchen. The ticking of the calculator keys is lost behind the sound of the radio. Tonight she has settled on easy-listening hits. It is always either that or Jesus-inspired, where a man of God talks about God. Eventually, he offers up some divine lesson that ends with the vengeance of the Lord, who always seems grumpy.

Humming along to some song as she switches gears, Gram prepares for her weekly trip to the grocery store the following evening. In the shorthand she learned in secretarial school, a million years before, Gram scratches notes on a pad of paper and organises coupons clipped from a circular into a tab-divided, accordion folder that fits neatly into her taupe purse. Everything is love, loss or eternal damnation. Jesus lived. Coupons save.

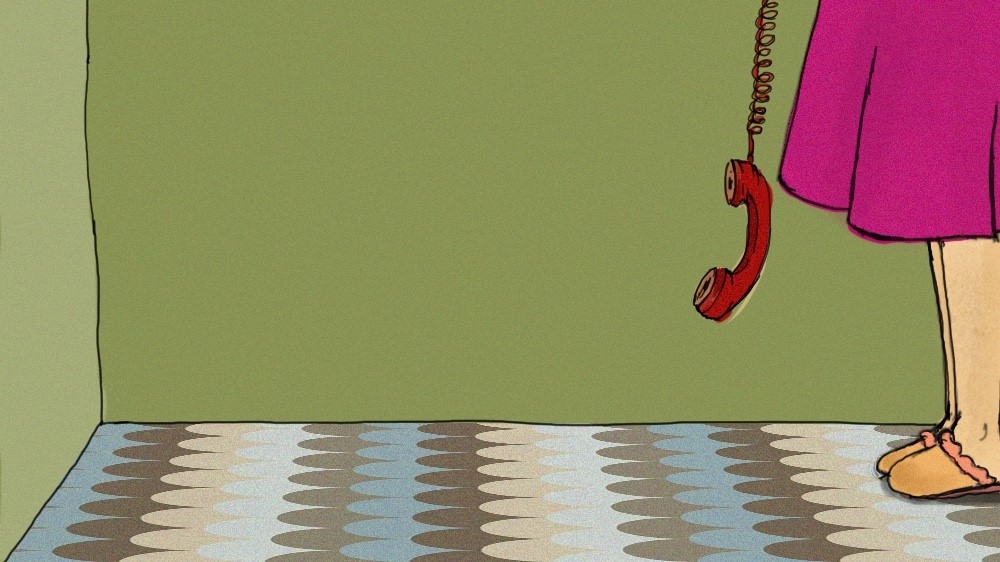

When the phone rings, my grandmother stops humming and shuffles towards it in slippered feet. She is still wearing pantyhose from work under a fuchsia house dress. “Hello,” I hear her say. A moment later, the phone dangles from a long cord before clanging against the floor.

My grandfather puts his paper down, jumps up from his seat, and rushes towards her. Ronald Reagan’s voice echoes throughout the living room. Gram is crying and I know that something has happened. Things have changed in some cataclysmic way. My grandmother never cries. It makes her mascara run, giving her the look of a demented raccoon. Life has come unhinged.

Family shows up a few hours later. When we open the door to greet them, they are either crying, offering condolences (which my aunt, the teacher, tells me is an adult way to say sorry), though I am not sure why, or handing food to my grandfather. He continues to add plates to the kitchen table until they overflow onto the counter. I wonder what it is about death that makes people so hungry. As I walk through the apartment clasping my doll, I see that no one is actually eating.

The small groups staggered throughout our apartment reminisce about moments with a mother I never really knew or say things like, “What a shame, she was so young”, or “Look at Rose, she is so strong.”

My grandmother avoids people, instead focusing on the many details that go into burying a human being. The sheer quantity of them is shocking. There will be a funeral mass at our local church followed by lunch because people deserve to be fed. It must be a rule because Gram uses her serious face, the one where she clenches her lips together after mentioning it to her youngest sister.

“But first,” another aunt whispers, “we’ll have to reach out to Eddie.” Eddie is my mother’s boyfriend. “He can help us have Denise’s body shipped home.”

Hearing her sister, my Gram snaps, “No, I think Eddie has done enough. I’ll contact the coroner.”

A body in the underbelly of a 747

My mother died in Los Angeles, on another coast so the call is a long-distance one. Usually, Gram waits until after 7pm to make those because it is cheaper then but the next day she calls as soon as she wakes up.

Mum’s remains are shipped back on a Delta flight, direct from Los Angeles to Boston. She is in a box bumping through the friendly skies along with other packages in the underbelly of a 747. I hear my uncle mention this one evening over a dinner of spaghetti and meatballs. My mother’s death brought with it enough food to feed an army. Gram says, “We’ll never be able to eat it all”, but my Italian family tries.

Later that evening, while I watch an episode of Wonder Woman, surprised by my invitation to sit on the couch, I imagine people sipping gin and tonics and smoking cigarettes, ticking off ash into tiny metal trays built into their aeroplane seats just above my mother’s body.

At the end of the week, the final fragments of my mother’s life are gathered together and delivered by a man driving a truck. He hands my grandmother the package. She takes the envelope, thanks him and adds, “Have a good day.” Gram believes even grief is not an excuse to forget the basic tenets of etiquette. “Thank you,” she adds, forever a slave to manners.

Mum’s biker boyfriend packed up her things and mailed them separately. My mother’s life fits into a manila envelope the size of the Dr Seuss book I read before bed at night. Shaking out the contents onto her bureau – a few rings, and some other jewellery – Gram looks up to the cross up on her wall. Crucified Jesus does nothing but stare.

I want to ask how they moved my mother from the airport to the church. I want to find out if the worms will root themselves inside of her organs and brain consuming bits and pieces of my mother once she is settled in the ground. My friend told me her older sister said that this is what happens to dead bodies. Instead, I watch Gram shove the remains of her daughter into the junk drawer she cleans out at least once a month.

Casseroles, cookies and a philodendron

It is around this time that the plant arrives. We look for a tag, but there is nothing, which makes it impossible to figure out who sent it.

At first, it sits on the counter in the kitchen. No one seems to know what to do with it. After a period of serious neglect, where the plant appears close to death, Gram begins to take notice. She trims it, taking care to pluck the shrivelled brown leaves that have rolled in on themselves and toss them into the rubbish. Bits of soil fall onto the white and yellow, oval-patterned linoleum floor. Gram pulls a dustpan out from under the sink, and I watch her sweep up the fallen debris.

Eventually, the plant finds a permanent home. Its sprawling leaves hang over the sides of the white refrigerator, a minor inconvenience we ignore. Occasionally, a leaf or vine gets stuck in the door or wrapped up in a magnet.

The plant is my pet now ... I can water it and feed it and maybe even put it in a wagon and take it for a walk around the neighbourhood. Maybe I will name it. Perhaps something dog-like - Fido or Spot.

Spring segues to summer. I see the plant whenever I walk along the driveway towards the fenced-in back yard. Our landlord has a dog named Queequeg. Years later I will find out that the dog’s name comes from a book about a villainous whale, one I will read in college. But at eight, it just seems weird.

While I spin in circles, holding my hands out and up towards the bloated clouds as they pass the sun, he barks from the house next door. I pretend he is mine. Gram does not want a pet. They are messy and loud like children, but you cannot ship them off to the babysitter for a snowstorm or a weekend of partying. Instead, they stay in the house waiting for walks and when they do not get them they defecate on the kitchen floor. Kid sh*t is necessary. Dog sh*t is not.

The plant is my pet now. At least, I think as I finally fall to the ground, dizzy and breathless from singing the same line from a Carly Simon song over and over, the plant is alive. I can water it and feed it and maybe even put it in a wagon and take it for a walk around the neighbourhood. Maybe I will name it. Perhaps something dog-like – Fido or Spot.

The plant was the most unusual thing we received after my mother died. Most people’s gifts did not require us to care for a living thing. They mail mass cards with images of the son of God, his beatific face glowing from above or stop by with sympathy cards with appropriate messages or hand-deliver tuna casseroles and homemade cookies – the plant comes from nowhere. I imagine the anonymous plant giver shopping for the gift. Perhaps, they moved past the lawn care items and towards the plants thinking, ‘Ah, yes, I’ll give a living thing to replace the dead one.’

“Rose, I’m sorry for the loss of your daughter,” I picture the person saying, “Here’s a philodendron.”

My mother, the plant

While the act of giving a gift when someone dies is kind, philodendrons are boring. They do not bud and flower. Even the instructions are basic: philodendrons grow best in medium or bright light, though they also tolerate low light. They are easy to grow houseplants that do not require frequent watering. The heart-leaf philodendron is harder to kill than to keep alive. They are a plant that requires little care to survive. With little to no effort, they grow and spread at an almost alarming rate.

I watch Gram pretend to want it until she really does. It is not that she hates the plant. Initially, I think she is afraid of it, the responsibility, the time it takes to care for something so dependent on her, the fact that the leafy thing in the kitchen needs her. Gram kills almost every living thing she ever tries to nurture. The few plants she owns struggle to survive, living on the limited water offered when my grandmother remembers to water them between her work as a secretary and her role as the wife of a social and functional alcoholic.

Though Gram is afraid, she tries. She uses a rust-coloured, plastic watering can, and we both marvel as the soil absorbs the water with a shocking ferocity that proves that all living things fight for survival. I imagine my mother fighting as the water fills her mouth while she lay seizing, drowning and dying at the bottom of a shower in an apartment in Van Nuys. Maybe she passed out before she had a chance to be afraid. Maybe she had not wanted to survive as much as the philodendron.

We have long, in-depth, though one-sided conversations. I tell it my problems - the boy who made fun of my bowl cut or my eye patch, the friend who did not talk to me, the brother who swore at me - and the plant listens better than any living thing I have ever known.

It is on our weekly trip to the grocery store that I discover an interesting fact. Two old people walk just ahead of us in the frozen food section. “If you talk to plants, they thrive,” I hear the woman tell her husband. He nods and adjusts his glasses. Watching as they head to the checkout, I decide to pick up a book at the library the next time I am there. Of course, at eight, I have a bit of difficulty reading the name of the German professor who first discussed the benefits of human conversation on plant life in 1848 when he wrote the book, Nanna (or about the inner life of plants). I ask my older brother to help but instead, he punches me on the arm and informs me that talking to plants is ridiculous. Ignoring him, I talk to the plant anyway.

We have long, in-depth, though one-sided conversations. I tell it my problems – the boy who made fun of my bowl cut or my eye patch, the friend who did not talk to me, the brother who swore at me – and the plant listens better than any living thing I have ever known. I worry that unleashing so much on such a delicate thing might have the opposite effect and cause undue stress for the leafy, sprawling friend who lives in our kitchen. The philodendron lives because or in spite of my efforts.

The following year, I hear from a friend’s older sister that the human soul can inhabit other living things, and so I come to imagine the green plant as my mother. Her long brown hair is replaced with leaves. Her thin body becomes the vines anchoring themselves in earth-coloured soil. Wondering if my grandmother, with her poisonous thumb, more black than green, will kill this plant as she has all the other living things, I wait for it to die, as the other plants of my childhood have, as my mother has, as I worry I might.

I breathe in the oxygen the plant releases, the one who becomes my mother. The one I talk to. The one that requires so little care. I breathe it in convinced the mother who died, the mother who never had a chance to care for me finally was – by feeding me oxygen, by listening to every problem as she sat atop the refrigerator, her heart-shaped leaves crawling throughout our kitchen reaching towards me as I ate breakfast or did my homework.

Giving life

And she lived, the plant, in our apartment and then our house as I grew and eventually left for college. My grandmother cared for her with such love, it overwhelmed me. I would stare at the leafy vines on every return home. Cutting pieces from the plant, my grandmother passes them along to family, so they can plant and grow their own philodendron. My mother becomes part of other people’s lives as well. She grows and spreads through our relatives’ homes, giving oxygen and life.

My mother was everywhere, witnessing our lives as if she were living with us. There were marriages and grandchildren and deaths. Through them all, she flourished in my grandmother, her mother’s home, for decades. Then, my grandmother got sick. Cancer spread through her body with the same speed and ferocity of the water absorbed by the philodendron, but it did not feed her. Instead, it absorbed the best parts of her, rooting them out and destroying them.

I got the call too late. Gram died surrounded by family as I was on the road racing to see her, racing to say goodbye. The text came as we crossed into my home state, “I’m so sorry.” When I entered the apartment, I walked into the silent room. Gram was gone.

Over the next few days, we cleaned out the apartment, dividing things up or donating them to Goodwill. And somewhere, somehow the plant – the one that witnessed so much, the one with heart-shaped leaves, the one that did not flower, the one that had managed to live in spite of my fears – disappeared. This was strange since it always remained in the very same spot, welcoming me on every trip home. It was gone as my mother had once been, as my grandmother was now.