An American lynching: ‘I could hear their screams’

How a mass lynching and the people re-enacting it are forcing the US to confront the truth of its past and its present.

Monroe, Georgia – A Confederate monument – a musket-strapped soldier perched atop a marble base – stands tall in the grounds of the historic Walton County courthouse in the city of Monroe, about an hour east of Atlanta, Georgia.

Erected more than 100 years ago, it is situated in the centre of the city’s downtown business district, whose blocks of quaint red brick buildings eventually give way to residential neighbourhoods where “Trump-Pence 2020” signs pierce freshly-cut lawns and Confederate flags flutter in the breeze.

Keep reading

list of 4 itemsUS: Atlanta mayor calls killing of Ahmaud Arbery a ‘lynching’

Ashes to Ashes: US Lynchings and a Story of Survival

Know their names: Black people killed by the police in the USThis article will be opened in a new browser window

Beyond the neatly-aligned homes are miles of vibrant green fields, once used as cotton plantations, and beyond those, down a short dirt road, is a small cemetery, with an old, white church at its entrance.

Among the wooden crosses, tombs and gravestones sits the shared headstone of siblings George Dorsey and Dorothy Malcolm.

The lives of 28-year-old George and 20-year-old Dorothy, along with those of their spouses, Mae Murray Dorsey, 24, and Roger Malcolm, 24, were cut short 74 years ago in the United States’s last documented mass lynching.

Their lives ended by the Moore’s Ford Bridge, a few miles from downtown Monroe, in a remote backwoods, but their story is one that can be traced back through the country’s violent past and forward to its troubled present.

‘I could feel their spirits’

Fifty-nine-year-old Patrice Dorsey’s mother was a cousin of George and Dorothy.

She refers to the Moore’s Ford Bridge, which traverses the Apalachee River and cuts through secluded forests of pine trees, brush and thickets, as the “killing fields”.

She first visited it over a decade ago.

“My heart just sank and tears came to my eyes,” she recalls. “I could feel their spirits there and I could hear their screams.”

“I felt so sad for what had happened to them.”

On July 14, 1946, Roger Malcolm, a Black sharecropper, was arrested for allegedly stabbing Barnette Hester, a white man who owned the farm Roger and his wife Dorothy were living on, during an argument. According to Anthony Pitch, an author and historian who dedicated the last six years of his life to uncovering the truth about the case, Roger had suspected for some time that Dorothy and Barnette were having a relationship.

Loy Harrison, a white landowner who employed Dorothy’s family, including her brother George and his wife Mae, agreed to bail Roger out in exchange for him working on sawmill operations he was starting at his farm.

On July 25, as Hester remained in hospital, Harrison arrived at the jail and paid a $600 bond to get Roger released. He was accompanied by Dorothy, who is said to have been seven months pregnant, George, and Mae.

According to Pitch, the FBI later learned that in Walton County a Black man was “never bonded out of jail while a white man’s life was in danger,” and that “prior approval” for his release would have had to have come from “interested” parties.

Harrison, who according to an FBI report had been a member of the Ku Klux Klan (KKK), never explained why he decided to take the longest route home from the jail, driving the couples toward Moore’s Ford Bridge, which links Walton and Oconee counties.

But as Harrison’s Pontiac sedan made its way over the wooden bridge, it was ambushed by a large group of white men. The mob, of about 20 to 25 people, hauled Roger and George, a World War II veteran, out of the vehicle, bound their wrists with rope and dragged them through the underbrush to the banks of the Apalachee River.

According to Harrison’s statement to the FBI, Dorothy and Mae started screaming, and one of them yelled out the name of a man she recognised from the mob – a name Harrison said he could not recall.

The mob responded by dragging the women from the car and down to the river bank.

At some point, a 10-foot-long (three-metre) rope was tightly bound around Roger’s neck.

Harrison said he heard the mob say, “One, two, three,” which, according to Pitch, some believed to be a ritual that preceded executions carried out by the KKK.

The two young couples were executed in three volleys of gunfire. The coroner’s report estimated that at least 60 shots had been fired at close range.

‘Blood and terror’

It was an act of collective violence like that inflicted upon thousands of African Americans throughout US history.

The Equal Justice Initiative (EJI), a rights group that has done extensive research on the history of lynching in the US, has documented 4,084 “racial terror” lynchings in 12 Southern states between 1877 and 1950, and at least 300 lynchings in other states during the same period.

Kiara Boone, the EJI’s deputy director of community education, explains that these numbers are most likely an “undercount”. According to the group’s data, lynchings in the US peaked between 1880 and 1940. Georgia was among the states with the highest number.

According to the EJI, Southern white communities used lynchings to assert “their racial dominance over the region’s political and economic resources – a dominance first achieved through slavery would now be restored through blood and terror”.

African Americans who had been arrested for an alleged crime against a white person were often kidnapped from jail by white mobs, with the collusion of local sheriffs, and lynched. The country’s criminal justice system was deemed “too good” for Black people, Boone says, and led to scores being killed without a trial or investigation.

Hundreds more were killed for non-criminal offences – such as protesting against mistreatment or violating various “Black codes” implemented to maintain racial hierarchies in the South.

Crowds of white people, at times numbering in the thousands, would gather for public lynchings, which could involve prolonged torture, mutilation, dismemberment and burning of the Black victims. The EJI describes these as “carnival-like events,” in which men, women and children would participate.

Following the lynchings, the spectators would excitedly grab “souvenirs” – pieces of rope, bloodied clothes, and body parts of the victims. Photographs of the lynchings, along with images of the mutilated and charred corpses, would be distributed.

‘Message crimes’

Lynchings were “message crimes,” explains Sherrilyn Ifill, the president and director-counsel of the NAACP Legal Defense and Educational Fund who has written a book on the subject.

“They were meant to send a message to Black communities about the boundaries of citizenship and their ability to be full citizens in this country – and that message was delivered through this particular form of terrorism.”

These lynchings were carried out by “ordinary people,” she says.

“Of course the KKK was involved in lynchings, but what made it more terrifying was the role of ordinary people – the people in the crowd who egged it on or actively participated. It could be the local pharmacist, elected officials, members of the high school football team, or law students who were present and watched the show.”

Lynchings were not just aimed at individuals, Ifill explains, but were commonly accompanied by “racial pogroms”. White people “marauded through towns and burned down Black businesses, causing tremendous property damage, and assaulted and beat up Black people they found along the way” – often accompanied by local police.

The EJI has documented how, in response to “routinely fabricated” allegations of sexual transgressions against white women, white mobs would “target entire Black communities with violent, public and sexualized acts,” including “the widespread rape of Black women, sometimes in front of their families; and genital mutilation and castration”.

It was a tool to keep “Black people in their place” to ensure racial subordination and white supremacy following the abolition of slavery, Ifill explains.

This collective violence against Black communities was also aimed at controlling the political or voting rights of African Americans.

In 1946, the year that the Dorseys and Malcolms were gunned down at Moore’s Ford Bridge, a contentious Democratic primary election for governor was under way in Georgia. Earlier that year, the US Supreme Court had ruled that the all-white Democratic primaries were unconstitutional; the 1946 elections were the first to be held in Georgia without a statewide ban on Black voting.

Eugene Talmadge, a gubernatorial candidate and well-known white supremacist, faced tough competition in the elections and escalated his inflammatory rhetoric against the Black community. It has been suggested that Talmadge’s campaign to incite violence against Black citizens to keep them from the voting booths contributed to the lynching in Monroe.

Talmadge, who is considered one of the most “racially polarising figures in Georgia history” and whose statue still stands on the grounds of Georgia’s state capitol, allegedly met with the brother of Barnette Hester in front of the Walton County courthouse shortly before the murders and offered immunity to anyone who would “take care” of Roger.

According to an FBI memo, the Monroe assistant police chief, who witnessed the meeting, believed Talmadge’s promise of immunity was intended to secure the support of the Hester family in the upcoming election.

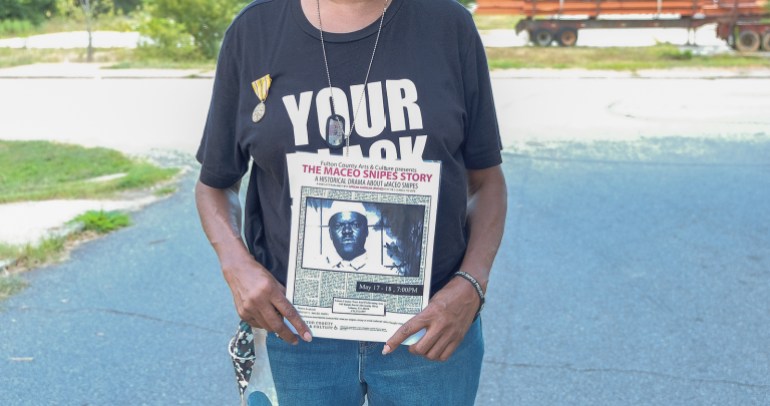

About a week before the Dorseys and Malcolms were slaughtered, Maceo Snipes, also a World War II veteran, made the bold decision to become the first African American to cast a vote in the July 17 primary in Taylor County, located about two hours from Monroe.

The following day, four white men, rumoured to be members of the local Klan chapter, arrived at Snipes’s grandfather’s farmhouse, where he was having dinner with his mother, called him outside and shot him in the back.

With the help of his mother, Snipes walked for three miles to a relative’s home, from where he was driven to a nearby hospital. Despite desperately needing a blood transfusion, Snipes was told by doctors that there was no “Black blood” available at the hospital.

Two days later, he died from his injuries.

An FBI investigation

The bodies of George and Mae Dorsey and Roger and Dorothy Malcolm were left unattended, rotting by the banks of the river for almost two days. During the night, white Monroe residents trickled down to the crime scene and foraged for pieces of rope, bullets and teeth.

Their murders prompted national outrage, says Laura Wexler, who authored a book on the case – partly because George Dorsey was a veteran who had served in North Africa and the Pacific.

According to Joe Bell, a lawyer currently petitioning the US Supreme Court to unseal grand jury transcripts from the case, protests erupted across the country and thousands of telegrams were sent to the White House demanding accountability for the lynching.

What followed was the “most extensive federal lynching investigation in the history of the nation at the time,” Wexler explains. President Harry Truman sent in the FBI, which interrogated almost 3,000 Black and white residents of Walton County during the months-long investigation.

Over 16 days in December of that year, more than 100 people testified in front of a grand jury. But despite the unprecedented time and resources put into the case, not a single resident of Walton County was indicted.

According to the EJI, out of all the lynchings committed since 1900, only one percent resulted in a perpetrator being convicted of a criminal offence.

‘Veil of silence’

Despite the widespread attention the lynching received, Hope Dorsey, Patrice’s sister, knew little about her relatives, George and Dorothy.

“There’s been some murmurs of what happened [in the family],” says the 52-year-old who lives in North Carolina. “But we never saw anything that confirmed it.”

“My mum didn’t want to talk about it because she was scared about what might happen. They left this town [Monroe] and never came back.”

Following lynchings, a hushed silence permeated Black and white communities.

“White people had a pact between them and understood that they were not going to tell what they knew and Black people were too afraid to speak because of fears of retaliation and reprisal,” Ifill explains.

There were times, she says, when the family of a lynching victim was too fearful to even collect the remains of their loved ones. “There’s no real place for the family to process the horror of what has happened to them or their loved one because the most important thing is to be silent and to be safe from reprisals,” she says.

Families were “living in absolute terror” and white people involved in lynchings lived in “perpetual fear that Black people might be planning something against them,” Ifill adds. “So you have this veil of silence that falls down within these affected families because they cannot speak their pain publicly.”

Scattered

The Dorsey and Malcolm families fled Monroe following the lynching, eventually becoming scattered across various states, including Ohio and North Carolina. The breakup of Black families and entire communities was repeated throughout the South during this era.

After lynchings “it was not uncommon to see the relatives or descendants of the person who was lynched flee the community or for the entire Black community to leave,” Boone explains. “It’s not a coincidence that a lot of these cities today [sites of violence against Black communities] are now majority white spaces.”

Between 1916 and 1970, more than six million African Americans relocated from the rural South to cities in the North, West and Midwest. The Great Migration, as it is known, is often framed as being driven primarily by the search for economic opportunities outside of the South, where about 90 percent of the African American population had lived.

But “a key role in the migration of [Black] people from the deep South was in response to racial terror lynchings and violence,” says Boone. “And when you’re forced to flee your home that carries with it a loss of income, property and resources that you can’t carry with you. And it often breaks up the family ties.”

As African Americans fled the South and flooded into cities like Chicago, Detroit, New York and Oakland, they were not welcomed as refugees or internally displaced people fleeing rampant and horrendous violence back home, but instead “faced job, housing and education discrimination that were perpetuated through realtors and local governments, and bolstered by federal legislation,” Boone explains.

‘Saying their names’

It was only when Patrice – sometimes referred to as the “historian of the [Dorsey] family” – saw an episode of the Oprah Winfrey Show in the 1990s that she understood the significance of the whispers she had overheard in her family.

On the show was Clinton Adams, a former Monroe resident who had come forward to the FBI, claiming to have witnessed the lynching as a 10-year-old child hiding in the woods.

“They were showing the Malcolms and Dorseys in their caskets. They were showing the whole story of my family,” Patrice, who lives in North Carolina, recalls, her voice still reflecting the shock she felt then. “That’s when it really sunk in. I remember tears coming to my eyes. I couldn’t believe I was looking at my relatives.”

Patrice began piecing together her family’s story and went in search of her long lost relatives, separated decades earlier when they had fled Monroe in fear.

But it was not until 2005, when the Moore’s Ford Movement – first spearheaded by Dr Martin Luther King Jr when he was still a student at Atlanta’s Morehouse College – began organising an annual re-enactment of the lynching that the estranged families started to find each other.

According to Tyrone Brooks, a veteran of the Southern Christian Leadership Conference (SCLC) and chairman of the Moore’s Ford Movement, the re-enactments, which are held every year on July 25 – the anniversary of the lynching – are aimed at making “sure America never forgets that lynchings were a common strategy to suppress, intimidate and kill people in this country – and we won’t allow America to hide from this past.”

For the Dorseys and Malcolms, the re-enactments also serve as a family reunion.

At this year’s re-enactment, conversations between relatives of the victims – some of whom were meeting each other for the first time – twisted around long and complicated family trees, as they searched for their common ancestry.

“The more we talk about what happened to our ancestors, the more the word gets out,” Hope explains. “Now Dorseys from Baltimore and Detroit to Louisiana and Alabama are responding to [the re-enactment], finding each other, and getting to know one another.”

“The lynching broke up our family, but in our fight for recognition and remembering what happened here in Monroe, we’re coming back together finally,” she says. “We’re saying their names and we want the world to hear it and we want the world to know what happened here.”

“Our family coming back together feels like closure to us,” she reflects. “We’ve been absent for so long, but now we’re here and even teaching the young generations about what happened to the Dorseys and Malcolms and remembering the violence they faced. I feel like now since their family is here, they can finally rest peacefully because we won’t let the world forget them.”

‘Another trophy for their wall’

Joseph Dorsey’s father was the brother of George Dorsey and Dorothy Malcolm.

“I would hear my father talking about it. He would bring it up now and then,” the 72-year-old recalls. “But it was mostly when he was drinking, so we didn’t pay much attention. I think that pain stayed with him throughout his life.”

Joseph, who lives in Georgia, says it was not until he grew older that he started to reflect more on his father’s stories about the murders. “I started to see all that stuff for myself. They tell you which doors you can walk through and which bathrooms and water fountains you can use,” he says of segregation.

“We lived through all that so our uncle’s story was something that we, ourselves, were living through.”

Joseph’s brother, 69-year-old George, who was named after his slain uncle, did not know about his relatives’ murders until he was at least in his 40s, “if not older,” he says, adding that he had not met his father until he was 13 years old.

The first time George visited his aunt and uncle’s gravesite was in 1999, when the Moore’s Ford Memorial Committee arranged for George Dorsey to receive military honours, which included a flyover by a World War II plane, during a ceremony in Monroe.

“We’re lucky we even know their names,” George says. “They’re many [Black] people who were killed and never identified. No one knows what happened to them or who they were.”

According to the EJI, hundreds of lynching victims’ names are still unknown because newspaper reports at the time failed to publish them.

“It’s awful sometimes how life is,” says George, who also resides in Georgia. “But what’s done is done and that’s how I look at it. They just kill Black people like deer and there’s nothing anyone’s going to do about it. It’s just another trophy for their wall. And it will keep going on that way because they keep getting away with it.”

“Justice will only come when he [Jesus Christ] comes back,” he reflects. “That’s when we’ll see some justice. On judgement day all of those people will get it. And if justice comes before then it will shock me to death.”

‘A lot of fear’

Several miles from the gravestone of George and Dorothy lies another tombstone, propped atop the more recently dug grave of Lynn McKinley Jackson, a 23-year-old army private and native of Monroe, whose decomposing body was found hanging from a pine tree in the woods outside Social Circle, a city in Walton County, in 1981.

A few months after his body was found, a jury ruled Jackson’s death a suicide, even though he would have had to climb a pine tree, with no branches, for 20 feet (six metres) straight to reach the branch he was found hanging from. Many residents and activists are convinced he was killed.

Jackson’s hanging remains still cast a shadow over Walton County, where street signs continue to bear the names of some of those suspected of having fired the bullets into the Dorseys and Malcolms more than seven decades ago.

“These lynchings tell us why our current reality is the way it is,” says 30-year-old BreAnn Robinson, a resident of Monroe and one of the founders of FORM, a local group established last year to push for reconciliation and transformative justice in Monroe.

“You can clearly see where the Black community starts and ends and where the white community starts and ends,” she explains. “There’s a clear line drawn and you can see the different socioeconomic statuses between the white and Black communities very clearly.”

“Growing up here, there was a lot of fear,” Robinson adds.

In Monroe, African Americans make up about 42 percent of the population, but there are only two Black city council members and all but one of the businesses in Monroe’s brick-layered downtown business district are white-owned, says Robinson.

A ‘direct descendant of lynching’

But it is not just in Monroe that the legacy of lynching continues to reverberate; communities across the US are haunted by it.

According to Boone, the criminal justice system replaced the white vigilantes as a central tool for suppressing the civil, political and economic rights of Black people.

In response to the worsening public image of Southern states, law enforcement and elected state officials began negotiating with the white mobs to hold state-sanctioned public executions as a way of mitigating the violence while still appeasing the white mobs, Boone says.

According to the EJI, northern states had abolished public executions by 1850, but some Southern states continued the practice until 1938, and at times succeeded in forcing public hangings even where it was illegal.

As early as the 1920s, the EJI says Southern legislators “shifted to capital punishment so that the legal and ostensibly unbiased court proceedings could serve the same purpose as vigilante violence: satisfying the lust for revenge”.

By 1915 court-ordered executions outnumbered lynchings in Southern states for the first time, while two-thirds of those executed in the 1930s were Black, according to the EJI. Although the African American population of the South fell to 22 percent between 1910 and 1950, Black people still constituted 75 percent of those executed in the South during that period.

The EJI considers the death penalty in the US to be a “direct descendant of lynching”. While only 13 percent of the country’s population is African American, more than 42 percent of those on death row and 34 percent of those executed are Black. In Georgia, someone convicted of killing a white person is 17 times more likely to be executed than someone convicted of killing a Black person.

“The states with the highest numbers of documented racial terror lynchings are also the states with the highest number of death sentences and executions today,” says Boone.

“These systems are rooted in the myths of racial differences and the idea that Black people are inferior, dangerous or criminal,” she explains. “These myths were created to justify centuries of enslavement, where Black people were treated as property and looked at as less than human. And that’s something that has lived on for generations.”

The case of Ahmaud Arbery, a 25-year-old Black man who was shot to death earlier this year while jogging in his neighbourhood outside Brunswick, Georgia, sent a terrifying, but all-too-familiar, tremor through Black communities. Two white men, Gregory and Travis McMichael, who killed Arbery after pursuing him in their pickup truck, were not arrested until months after the murder – and then only after a video of the incident went viral and national outrage erupted.

From police killings to vigilantism, “all of that is anchored in this history of racism and how we devalue and dehumanise Black people, and the lack of accountability that we continue to see when violence is carried out on Black people in this country,” says Boone.

‘The root of all of this’

Despite being raised in Walton County, Robinson did not learn of the mass lynching that took place there until 2017, when she stumbled upon a flier for the annual re-enactment. “I was so shocked,” she recalls. “I was raised here. I went to school here and studied history here. My family is from here. And I had never heard about it.”

“It was a big eye-opener for me. There was a huge investigation, even the president got involved. And no one decided that we should be taught this? It showed me that those in power do not care about the Black community.”

“I then decided to dig deeper, learn more, and understand why this veil of oppression is still hanging over this city,” she adds. “And what I’ve learned is that a lot of those individuals who were part of the lynching, their families owned a lot of land and they had a lot of power. And all of these families are still in power to this day.”

According to Robinson, most of the Black community in Monroe “still doesn’t like to talk about the Moore’s Ford lynching because they’re still scared”. But some white residents, who are descendants of suspected lynchers, have stepped forward to participate in FORM’s activities. “They feel ashamed for what their relatives did and they want to say this isn’t who they are,” she explains.

Robinson, along with the rest of FORM’s members, is advocating for the removal of Walton County’s Confederate monument and the erection of a central memorial for the Dorseys and Malcolms, as well as for July 25 to be declared a city-wide day of mourning. Activists around the country have also advocated for reparations for families affected by lynchings.

“This is our history and justice still hasn’t been served,” Robinson reflects. “Think about all the families who still haven’t received justice for their children brutally killed by police or white vigilantes. These lynchings are the root of all this. If we let this history die, then they win. And since it’s not written in our history books, it’s our responsibility to make sure this country doesn’t forget.”

Boone believes that efforts to document or memorialise victims of lynchings are “a way of adding to the work of truth-telling, which is desperately needed in this country”.

“Our goal should be about truth and justice. We need to really recognise and confront the truth of our past,” she explains.

The EJI opened The Legacy Museum: From Enslavement to Mass Incarceration in Montgomery Alabama in 2018, along with the country’s first national memorial to the thousands of African Americans killed by white mobs during the era of lynching.

Todd Dorsey, Patrice and Hope’s brother, is still waiting for the day he feels closure for the massacre of his relatives on Moore’s Ford Bridge.

“We need something, even if it’s an official recognition or an apology,” the 60-year-old says. “These were human beings and we want that to be recognised. There are memorials for Confederate soldiers and even the names of those men who killed them are still on Monroe’s street signs, but our relatives’ names are only written in the cemeteries.

“But we’re still here,” he adds. “We’re the remnants. We’re the seeds of our ancestors. Back then, people were too scared to speak, but now we’re here and we’ll always fight until we get justice for them.”