How should we talk about suicide?

After my brother’s suicide, I know we need to find a way that protects those at risk while freeing those impacted.

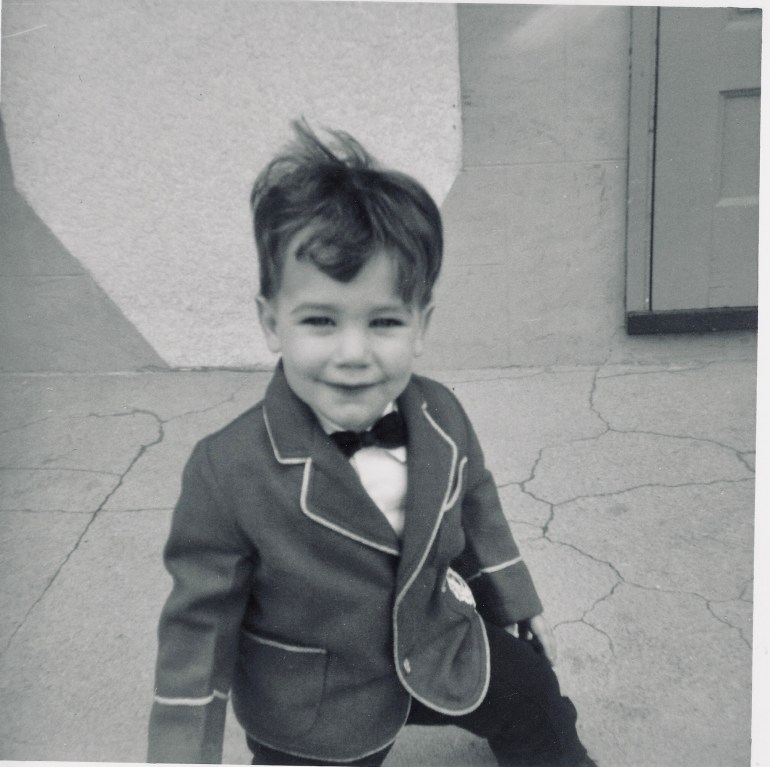

It has been three years since I got the call about my brother; my 49-year-old, funny, sentimental, handsome, troubled younger brother.

It is a call no one can prepare for and one that is accompanied by a tsunami of confusion, anger, disbelief and unimaginable despair.

Keep reading

list of 4 itemsIs the climate crisis creating a mental health crisis?

The culture of dying

The scents of our grief

My brother’s suicide was a tragedy on many levels and, like most people who have endured this kind of loss, I was overwhelmed by contradictory emotions when I was told he was gone. How could he do this to our parents, to his kids, to our family, to me? Then, mixed up with my fury, came the guilt. Why didn’t I answer the phone when he rang that day? Why didn’t I tell him I loved him?

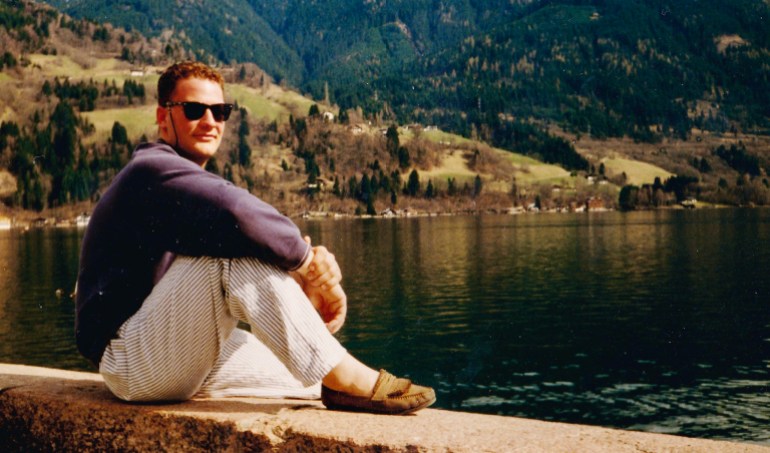

My brother grew up in a loving middle-class family with summers at the lake and friends all around. He was a talented athlete and a professional ice hockey player. He had lived in Canada and Europe, run a successful golf business, had a beautiful wife and two wonderful children.

Despite all this, he struggled with demons none of us who loved him could understand. He slipped into drug and alcohol abuse, lost his family and landed in a toxic relationship he knew was destructive.

Ultimately, ending the life he found unbearable became a more powerful option than learning how to fight for the life he deserved.

When my brother died I was thrown into a cycle familiar to many people who have lost someone in this way. I was tortured by ruminative thoughts; conversations with myself that went around and around in my head. If only I could go back, change that one thing, unsay those words, make it different. If only I could reverse time. But I can’t. Time only goes forward and no matter how many circular scenarios plague my imagination, I can’t change what happened; I can’t reverse time and that is hard to accept.

‘We can’t ask people to see the world through our eyes’

One of the strangest ironies of the situation I found myself in three years ago was the fact that when my brother died I was making a documentary about suicide. As a filmmaker I had often worked on projects that were close to my heart but never before had my life and my art so tangibly collided. Oddly, despite a brief moment when I considered walking away from the project, this bizarre twist of fate came to be a blessing. While working on the film I was exposed to people who knew what I was going through and could help me survive the emotional rollercoaster I was riding.

From them, I learned that while my initial reaction to my brother’s death was to judge him as selfish, it is likely that in his mind the opposite was true. It is possible that for a brief, misguided moment, he believed his fatal decision would release our family from the strain of supporting him – that he was a burden and that, by exiting from our lives, he would be doing us a favour.

He was wrong of course, but when people are as distressed as my brother was they do not see the world the way we do, and this too is a lesson. We cannot apply the logic of our lives to the chaos in theirs. My brother was in pain; his suffering was impossible for me to understand because I haven’t experienced suffering like it. His pain was his own and asking him to think or feel the way I did was a mistake because my life experience had little in common with his. So, when I tried to reassure him that everything would be fine if he “just” did X or “just” said Y, I wasn’t acknowledging his reality – things weren’t fine and my saying they would be didn’t change that for him. We can’t ask people to see the world through our eyes, we can only try to help them see past the darkness blocking their view.

‘I couldn’t fix my brother’

I don’t want to imply that my brother bore no responsibility for the circumstances he found himself in. He made numerous bad choices, wasted many opportunities and often didn’t take advantage of the help that was offered to him. Both my parents exhausted themselves emotionally and financially trying to “sort him out”. There were endless discussions about tough love, enabling, interventions and what he “really” needed. None of us had an answer and I now feel that too many of these conversations were had without him in the room.

Added to this is the compassion fatigue I and others faced when dealing with my brother and his “issues”. He tended to reach out when he was in crisis and there were many late-night, early morning or simply ill-timed phone calls that went on for hours. Drunken, stoned, sometimes desperate calls I had to steel myself for; calls that exasperated and exhausted me – calls I came to avoid, including the one I didn’t answer the day he died.

Would answering my phone have helped? I will never know for sure and there-in lies one of the internal circular dialogues I still navigate. But what I now understand is I couldn’t have saved him, because we can’t save people – we can only be there to help them save themselves. This might sound trite, but it is a truism that is difficult for someone like me. I like to fix things and I couldn’t fix my brother.

Unlike many people who take their own lives, my brother had never attempted suicide before. He left no note to help us understand his state of mind nor did he leave me a message that day. He had been struggling with addiction issues and depression for a significant period of time and while he had been in and out of rehab in the months leading up to his death, I thought he was doing ok. I did know, however, that his connection to hope was tenuous and, in a pattern I had become accustomed to, his slide into despair was rapid; in this case too rapid for me to respond.

The debate about what should and shouldn’t be said about suicide goes on. There is reticence when talking about it as we fear triggering the vulnerable. Although I accept there is risk in everything we do, I would argue the silence that shrouds this topic makes it more difficult for those of us left behind. And there are so very many of us left behind. It seems that any time I mention my brother’s death, the person I am talking to has a story of their own. The parent they lost, the sibling, the child, the friend, the lover. It is ubiquitous and the often-whispered tones that relate melancholy stories illustrate to me the shame that taints the subject of suicide and those of us touched by it. We are admitting failure; my love wasn’t enough to keep my brother alive.

I felt this failing most keenly when I finished my documentary. I had buried my grief beneath its making, convincing myself that there was a reason I was doing this thing at this time, and there was. But when it was done and my brother’s name appeared in honorarium as the final credits rolled – I fell apart. I had made a film that addressed the issues that had, in part, led to my brother’s death, it was meant to mean something – but he was still dead.

‘I will always wonder’

For my parents, the weight of losing my brother was to prove overwhelming. My 78-year-old father’s health collapsed almost immediately and he died six weeks later, I believe, from a broken heart. My mother, who had been a young 75, not long retired and physically formidable, aged exponentially and has subsequently struggled to recover. The only glimmer of light in what was a dark time was the way this long-divorced couple came together in their grief.

I wish I could say that in the three years since my brother’s passing I have had an epiphany of some kind or that I have deep effectual insights to share with others who inhabit a similar space; but I haven’t and I don’t. There are still days when I’m consumed by sadness and I find it difficult to explain the hollowness I feel inside to those close to me. I am fundamentally an optimistic person, but at times it is hard to maintain that outlook and we do the truth a disservice by pretending it is not. Helping people deal with mental illness is crucial if we want to stem the rising numbers of those choosing to take their own lives. We also need to ensure when the outcome is not what we would have wanted that the grief-stricken find the understanding and support they need, too. Once suicide has permeated our psyche it is with us forever. I have found a way to live with the hole in my heart but the hole will always be there. I will never stop loving my brother and I will always wonder what he rang to say that terrible day.

The one thing I feel certain about is that we are failing to find a way to discuss suicide in a manner that protects those at risk while freeing those impacted. I am not sure what the answer to this problem is but we need to keep looking for it or we condemn millions of families, lovers and friends to lonely bewilderment and endless anguish. For now, all I can do is remind myself that my brother’s life wasn’t just about his ending and there are wonderful memories to be cherished alongside the ones I need to let go.

If you or someone you know is at risk of suicide, these organisations may be able to help.