How a Greek reporter could help put neo-Nazis behind bars

Reporter Dimitris Psarras has spent decades investigating one of Greece’s most violent far-right groups, Golden Dawn.

Athens, Greece – When the package arrived at Scholiastis’s offices in the Greek capital one morning in early 1988, the magazine’s editorial staff made up their minds without much hesitation: they would not publish the documents – information about a little-known neo-Nazi group calling itself Golden Dawn.

Rather, they wrote a quick editorial explaining why publishing the materials would set a dangerous precedent for a magazine with a 15,000-strong circulation. “We answered by saying we would not begin a dialogue with Nazis,” said Dimitris Psarras, who was an investigative reporter and editor at Scholiastis at the time.

Keep reading

list of 4 itemsGermany bans far-right Austrian nationalist Martin Sellner from entry

Australian efforts on Islamophobia flag despite Christchurch wake-up call

Norway court says mass killer Breivik’s prison isolation not ‘inhumane’

The following month, Golden Dawn’s magazine took aim at Psarras and his colleagues, denouncing them as communists and insisting that they only understood the language of “the fist”.

A package and a trial

Then 34 years old, Psarras had taken up journalism five years earlier. His path to it had not been linear; he had been involved in socialist student activism and worked as an architect before becoming a reporter.

In 1983, he cofounded Scholiastis, a left-wing weekly political magazine he says offered hope to young reporters in the decades following the end of Greece’s military dictatorship, which had collapsed in 1974. Democracy followed, and the lack of state censorship changed the media landscape. “It was the first left-wing magazine that tried to be critical in the time of lifestyle journalism,” he explained. “It was a kind of school for many new journalists.”

Prone to letting papers and files swell into small mountains, Psarras absentmindedly placed the package on his desk, and it ended up buried beneath the papers and notes that accumulated there over the following months. “Nobody thought this tiny organisation would have an impact on Greek politics,” Psarras reflected.

But 31 years later, the party’s early statute – a document included in that package, alongside a breakdown of protocols and a few issues of Golden Dawn, the national socialist magazine the group published – is at the centre of an ongoing trial that could place Golden Dawn’s leadership behind bars.

“At that time, they were trying to make some noise around themselves,” Psarras said, explaining why he thinks they mailed the package. “We have the evidence that they sent us all these documents that they now deny exist.”

Tracking Golden Dawn

Now a 67-year-old veteran reporter, Psarras has spent a large chunk of his career tracking Golden Dawn and has published seven books on topics including the country’s radical right and the military dictatorship that ruled Greece between 1967 and 1974.

After rising from relative obscurity to become the third-largest party in the country, Golden Dawn is now facing an existential crisis. Last summer, voters ousted the party from the Hellenic Parliament, an unexpected development that saw the party’s coffers dry up and many of its longtime members jump ship.

When, following the September 2013 murder of a left-wing rapper, 69 members of Golden Dawn were put on trial on charges of belonging to a criminal organisation, Psarras provided the prosecution with the contents of the package Scholiastis had received almost three decades earlier.

Those files are now among the thousands of pages of documents the court has considered since the trial started in April 2015.

“It is important because they are still denying that this is their statute,” explained Electra Alexandropoulou, the coordinator of Golden Dawn Watch, an Athens-based initiative established to monitor the ongoing trial. “In the statute, [they] detail their operational motives. You can see how important it is from their reactions. They say it is Psarras’s fabrication.”

Testifying

Having carved out a reputation as the country’s foremost investigative journalist reporting on Golden Dawn, Psarras has taken on a crucial role in the trial.

On the 185th day of the trial, one morning in early October 2017, few journalists and observers turned up at the Athens Court of Appeals, and none of the defendants were present. Wearing a slick black suit over a white dress shirt, Psarras clutched some papers. He would come every day to watch the proceedings, but he was there that day to testify.

In his testimony, which would go on to span three hearings, he started out recounting Golden Dawn’s early history and the ideology that had guided the party since its inception. Golden Dawn’s ideology was rooted in white supremacy, its modus operandi centred on violence, and its aesthetics modelled on Nazi Germany, he explained to the courtroom.

Psarras held up the original statute mailed to Scholiastis, which differed dramatically from the updated version the party submitted to the Supreme Court in 2012.

Core to Golden Dawn, he said, was the centrality of the leader. “There is no Golden Dawn without [founder and leader Nikolaos] Michaloliakos,” he told the judge when asked if the group truly existed in the early 1980s. “Michaloliakos is Golden Dawn.”

By the summer of 2013, as the party surged in legislative elections, Golden Dawn had started to think of itself as immune to serious legal backlash, Psarras added. After all, one of the party’s eventual parliamentarians, spokesperson Ilias Kasidiaris, had gotten away with slapping a female politician three times on live television in June 2012. Others in the party had not been arrested after attacking migrant vendors in open-air markets, smashing their tables and beating them with flagpoles. Some black-clad members had ridden in motorcades, intimidating and attacking refugees and migrants in impoverished central Athens neighbourhoods. Years of violence had failed to elicit a meaningful response from the government and its police forces – and some officers stood accused of encouraging and facilitating it.

He thumbed through the pages of Strike Team Lance, a crudely-written, Greek-language novel of speculative fiction. The book drew on themes that first gained widespread currency in American white nationalist William Luther Pierce’s infamously racist novel The Turner Diaries, which envisioned an unavoidable race war in North America. Published under the pseudonym N Exarchos, Strike Team Lance was actually written by Golden Dawn chief Michaloliakos, Psarras told the courtroom.

Throughout the three days he testified, one statement stood out for its brusque clarity: The statute he had brought with him, Psarras said, demonstrated that Golden Dawn was nothing more than “a purely Nazi organisation”.

‘Fanatical neo-Nazis’

As he had in the courtroom, Psarras always showed up for our meetings with receipts. Each time I sat down with him at the offices of Efimerida ton Syntakton, the newspaper where he now reports, he came equipped with a thick folder full of documents. He dressed casually – almost always carrying a backpack and rolling up the sleeves on a button-up flannel shirt, more times than not hastily tucked into his jeans.

Leafing through articles and documents in his office, he spoke about Golden Dawn and Greece’s broader far right with the type of encyclopaedic knowledge generally reserved by researchers immersed in a subject for decades.

He is not the only reporter to produce crucial investigations into the group’s often bloody activities – he is quick to point out that his colleagues have done equally important investigative work on the party – but few out there can discuss the minutia of it with the same degree of fluency.

From the time Psarras first focused so much of his energy on Golden Dawn until now, his hope has remained the same: He wants to see accountability for its crimes.

On more than one occasion, he rattled off a list of Golden Dawn’s internal power struggles, the intra-party clashes of egos, and the type of nuances that often fail to make their way into reporting on the party. All complexities aside, his overall assessment of Golden Dawn remained as strikingly simple as it was during his testimony years earlier. “They are fanatical neo-Nazis,” he told me during one interview, his face stern.

An earlier encounter

When Michaloliakos launched the National Socialist journal Golden Dawn in 1980, Psarras was already familiar with the far-right activist who had been imprisoned on explosives charges in the late 1970s and had been active in 4th of August Party (K4A), a neo-fascist group whose name paid tribute to Greece’s World War II-era dictatorship.

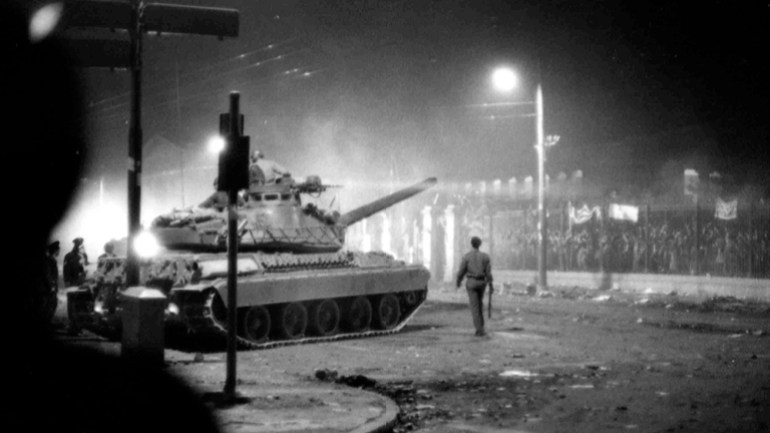

Psarras had his first run-in with Michaloliakos in 1973, not as a reporter but as a student activist. At the time, Psarras was a member of a left-wing committee that launched the strike that morphed into the Athens Polytechnic uprising. During the upheaval, Greece’s military junta deployed soldiers to the central Athens campus. As security forces besieged the university grounds, trapping the students inside, a band of enthusiastic young K4A members – among them the then 16-year-old Michaloliakos – lined up behind the heavily-armed police squads and hurled stones at the students inside.

“I saw a group of youngsters behind the police line,” Psarras recalled. “They were trying to provoke us with [pro-junta] slogans, and by throwing stones, and there were some stones thrown from our side; but we were a thousand, and they were tens.”

Neither Psarras nor Michaloliakos could have known it then, but they were standing on opposite sides of a conflict that would simmer for the next 30 years. Ultimately, the K4A affair marked only a passing moment in the Polytechnic uprising, which climaxed when the junta sent a tank crashing through the university’s front gates and killed dozens of students. Psarras narrowly escaped after slipping out through a side entrance and finding refuge among the sympathetic tenants of a nearby house.

A year later, the junta collapsed and Greece transitioned to parliamentary democracy. Psarras eventually graduated with a degree in architecture.

Becoming a political party

In 1985, five years after founding the national socialist journal, Michaloliakos split with the pro-junta National Political Union and registered Golden Dawn as a political association.

In the pages of the Golden Dawn magazine, Michaloliakos and other contributors regularly praised German Nazi officials, including leader Adolf Hitler, and promoted the intense strand of Holocaust denial for which the publication became notorious. (Later, when Golden Dawn entered parliament, its lawmakers used the podium as a platform for Holocaust denial, which Greece banned in 2014.)

In May 1990, Psarras joined a three-person investigative team known as Ios (Greek for “virus”) at the Eleftherotypia daily newspaper. Each Sunday, they published four pages of material.

Granted complete editorial independence, Ios produced investigations into a broad array of issues throughout the 1990s and into the early 2000s: it covered espionage, international and domestic terrorism, the role of Greek Orthodox fundamentalists in politics, and doping in Greek sports, among other issues of the time.

Psarras dug into many of these stories, but he also carved out an expertise on the country’s small but increasingly vocal far right. In October 1990, he published his first story breaking down the documents Golden Dawn had mailed to Scholiastis more than two years earlier. “I don’t think many people knew or were interested in [Golden Dawn],” he said of that time. “In this article, for the first time I published long sentences from their statutes.”

Golden Dawn occupied only a small slice of the political fringe, but he felt it was important to keep tabs on the group’s activities. After inaugurating a long streak of political violence during rallies over Greece’s longstanding name dispute with its northern neighbour, the Republic of Macedonia, in the early 1990s, Golden Dawn was eventually recognised as a political party in 1993.

Although the party failed in its early electoral efforts – gaining a tenth of a percent in the 1994 European Parliament elections and 0.07 percent in the 1996 legislative vote – it quietly built up a base of hard-core supporters.

‘We had a problem’

In 1995 the Greek Volunteer Guard was formed – reportedly including Golden Dawn members – and went to Bosnia, where its militiamen joined the Belgrade-backed Serb militias in their war on Bosnian Muslims. At around the same time, Psarras and his Ios colleagues observed an uptick in violent, far-right attacks on left-wing activists, a development that further assured him the group warranted attention.

“As a team, we saw that we had a problem as a society, as a democracy,” he said. “Even when Golden Dawn members were put in court or jail, nobody saw that there was an organisation behind this. Everybody saw this as an individual or personal problem.”

When Michaloliakos first gained a seat on the Athens City Council in 2010, Psarras feared the worst was yet to come. “I was sure they would [eventually] be in the parliament,” he recalled. Popular Orthodox Rally (LAOS), a far-right party that joined the governing coalition after winning 15 seats in 2009, was shedding support over its backing of the first bailout package in 2010, and the deepening economic crisis drove its former supporters even further right. Altogether, the situation presented a historic opportunity for Golden Dawn.

By the time the party achieved nationwide electoral prominence in a pair of 2012 legislative votes, its members had been carrying out attacks on political opponents and migrants for years. Harnessing the anger and desperation stemming from the country’s brutal economic crisis, Golden Dawn appealed to voters with a hardline programme rooted in fervent xenophobia, anti-European Union sentiment, and anti-austerity politics. Golden Dawn organised blood drives and food banks with a catch: their services were reserved solely for Greeks.

A blueprint for the far right

In October 2012, with Greece still reeling from Golden Dawn’s recent surge, Psarras published The Black Bible of Golden Dawn, a deep dive into the party’s history, ideology and activities.

Drawing on decades of research and reporting, the Black Bible was widely considered the country’s most ambitious book-length journalistic work dedicated to uncovering the party’s shadowy origins, its National Socialist ideological roots, its ties to fascist groups around North America and Europe, and its highly successful strategy of simultaneously fomenting far-right violence while infiltrating electoral politics. In effect, Psarras concluded, Golden Dawn had gone from modelling its own operations on far-right organisations abroad to offering a blueprint for like-minded groups the world over.

Anyone who hoped that Golden Dawn would tone down the violence after entering parliament would later be let down. As Golden Dawn parliamentary candidate Alexandros Plomaritis told filmmaker Konstantinos Georgousis during the 2012 filming of the documentary The Cleaners, “The knives will come out after the elections.”

And come out they did; first when a pair of Golden Dawn supporters knifed to death 27-year-old Pakistani migrant worker Shahzad Luqman in January 2013, and later when party member and employee Giorgos Roupakias stabbed and killed 34-year-old anti-fascist rapper Pavlos Fyssas.

After Fyssas’s murder prompted nationwide rallies against the party, Greek authorities belatedly cracked down on Golden Dawn, arresting dozens of members. Today 69 Golden Dawn members – including much of its senior leadership and its entire 2013 parliamentary group – are named in that trial, facing charges of operating a criminal organisation.

The crackdown initially did little to weather Golden Dawn’s electoral support. Legislative elections in January 2015 saw it propelled into parliament again, this time as the third-largest party in the legislative body, and it retained its parliamentary presence in another vote in September of that year.

It was not until July of this year, during snap elections, that Golden Dawn suffered in the polls, failing to overcome the three-percent threshold necessary to enter parliament and losing all of its seats.

Delays, strikes, and bureaucratic complications have allowed the trial to drag on. When the COVID-19 pandemic paralysed Greece and much of the world, the trial was yet again paused. As Greece began to reopen, proceedings resumed on June 17 and lawyers representing the victims urged the court to speed up the pace at which hearings are held.

Risky business

Since publishing The Black Bible of Golden Dawn in 2012, Psarras has continued to cover Golden Dawn and other groups on the radical right, unearthing new details about the party’s involvement in violence and criminal activity. Three of the five books he has published since The Black Bible focus on the far right, while the other two provide historic accounts of the military junta he protested against more than four decades ago. His most recent book, The Chief, was published in December 2018. The 367-page tome traces the ascent of Golden Dawn leader Michaloliakos. He dedicated the book to the mother of rapper Pavlos Fyssas.

There are risks, however, to his work. He was almost attacked in 2009, during an appeal hearing in the trial of Antonis “Periandros” Androutsopoulos, a former Golden Dawn member belatedly convicted for the attempted murder of a left-wing student activist in 1998. When Psarras, who was sitting near the prosecution, attempted to take a quick photograph of several Golden Dawn members who had leapt to their feet and started chanting, some of the men lunged in his direction. Ironically, Psarras says it was Periandros’s intervention that stopped the would-be attackers. (“It was a mistake to not let them take him out,” Periandros later said of the journalist during a different court hearing, according to Psarras.)

The incident did not rattle Psarras. Nor was he fazed by the numerous articles in the party’s newspaper painting him as the enemy of the nation or the handful of cryptic threats he has received throughout his career.

Those brushes with violence aside, Psarras is one of the luckier reporters on Greece’s far-right beat. After Ethnos newspaper reporters Maria Psara and Lefteris Bidelas uncovered alleged criminal activity by Golden Dawn, party spokesperson Ilias Kasidiaris filed a 300,000 euro ($356,000) lawsuit against the duo in December 2017. Others have been on the receiving end of brute force. For instance, in January 2019, far-right protesters beat, bludgeoned, and robbed a handful of reporters and photographers during protests against the Macedonia name accord between Athens and Skopje. One of those reporters, freelance photographer Kostis Ntantamis, had 13 stitches to his head after attackers battered him with a flagpole, making off with his camera in the process.

Dodging a mob

Over the last five years, I have attended several court hearings and a handful of Golden Dawn rallies in Athens and elsewhere. Although I managed for years to document their demonstrations without being noticed, I witnessed earlier this year how quickly violence could erupt during their gatherings.

It was a sullen grey Sunday afternoon in January, and I drove under skies knotted with clouds. I headed to downtown Athens because I had heard an anti-refugee rally was shaping up in Syntagma Square. I parked on a residential street far enough away to lose anyone if someone followed me back later.

My phone rang as I stepped out of my car. It was a colleague and friend, photographer Nick Paleologos, and he told me that German reporter Thomas Jacobi had just been attacked by a mob of masked men at the rally. Do not go into the rally, he warned me.

I ignored his warnings and waded into the crowd, snapping a few quick photos with my phone: a banner that read “Stop Islam”; another that declared “Refugees not welcome – close the borders”. Around half an hour earlier, Jacobi had been thrown to the pavement where I now stood, and beaten. Now a few young men, slipping on balaclavas and gripping flagpoles, were whispering among themselves and eying me with suspicion. I approached a maskless guy standing next to them and spoke loudly in English.

“Can you tell me what that banner says?” I asked. “I’m just passing through, and I don’t read much Greek.”

“Yes,” he said. “It says, ‘Close the borders.'”

“So, this is a protest for the islands?” I asked, referring to the recent uptick in refugee boats washing up on the shores of several Aegean Islands.

“It’s all of Greece,” he replied. “The refugees are attacking all of Greece.”

“Thanks,” I said, and walked off quickly. As I cut through the crowd, beelining towards a group of colleagues posted up on the far side of the square, I had the feeling of having narrowly dodged a thorough mobbing.

The crowd clapped as a speaker took shots at Greece’s migration policies, which, he said, had turned the Mediterranean nation into a “Muslim country”. Halfway across the square, a police officer stopped a pair of men lugging suitcases down the stairs. They were speaking Punjabi. He advised them to walk the long way around the rally – solid advice, as I saw it.

‘Subhuman, trash, scum’

The Golden Dawn trial reached a crucial moment last autumn. The party’s leaders, having boycotted most of the hearings throughout the last four-and-a-half years, started taking the stand, doing their best to dismiss the accusations against them. In October, when confronted with his own descriptions of migrants as “subhuman”, “trash” and “scum,” high-ranking party member and former parliamentarian Ilias Panagiotaros told the courtroom that he had only been referring to migrants who committed crimes. (He also begrudgingly admitted that, according to his estimation, 99.9 percent of migrants were criminals.) The violence, Panagiotaros claimed, had been the work of local chapters, which prompted the party’s central leadership to punish the culprits.

Earlier that month, another former Golden Dawn parliamentarian, Nikos Michos, sought to shield the leadership from legal retribution, claiming that Michaloliakos had never instructed his followers to carry out attacks or other crimes. During his testimony, however, he admitted that Golden Dawn jackboots raided a home in Perama in June 2012 and attacked sleeping Egyptian fishermen with wooden clubs. Michos revealed that Michaloliakos had been made aware of Fyssas’s murder only hours after the rapper bled out in the street, unwittingly contradicting the leader’s long-held claim that he had not known of the murder until the following day. At the time of publication, Golden Dawn’s press office had not replied to a request for comment.

With even more gruesome details of Golden Dawn’s activities emerging during the trial, the alleged perpetrators scrambled to deflect accusations that they were responsible for the bloodshed. Meanwhile, Psarras’s investigative journalism assumed heightened significance.

Thanasis Kampagiannis, who represents the Egyptian fishermen in the civil suit portion of the Golden Dawn trial, said Psarras and his colleagues covered the neo-Nazi party for so long and so thoroughly that their work had helped lay the foundations for understanding the “ideological structure of the organisation and also their criminal actions”.

Kampagiannis explained that Golden Dawn had given Psarras the nickname “Javert”, a reference to the main antagonist of Victor Hugo’s Les Miserables, a police inspector obsessed with tracking down protagonist Jean Valjean, who had spent time in prison for stealing bread to feed his sister’s children. Javert’s quest to have Valjean punished leads to emotional decay and his eventual suicide by drowning.

As far as Kampagiannis is concerned, the nickname misses the mark – implying that the party was only driven to criminality by desperate circumstances – but it also hints at the significance of Psarras’s “personal imprint” on the party and the trial. “I believe that Dimitri’s intervention on this case is very important from every perspective,” Kampagiannis explained.

Abandoned

Now out of the parliament and shedding its formerly loyal supporters, Golden Dawn for a time shut down and boarded up the offices where it had plotted its political future. Last autumn, the party’s once-lively Athens headquarters, a slate grey five-storey office building on Mesogeion Avenue, sat quiet and abandoned. The massive banner depicting Michaloliakos’s bespectacled face was no longer draped from the building’s windows, and torch-wielding party supporters no longer assembled for boisterous rallies in the street out front.

Across town, another former party office showed few signs that Golden Dawn had ever occupied it. Across the street, pro-Golden Dawn graffiti remained on a retaining wall – “We want our county back”, it declared – but the party’s red-and-black flags, bearing its swastika-like emblem, no longer flew from the balcony overlooking the impoverished borough in central Athens. Meanwhile, internal power struggles had turned members against each other.

At almost every court hearing, Psarras shows up and sits near the front, typing up notes on his laptop. He continues to write regular dispatches based on what he learns during the trial, drawing context and historical significance from his decades of reporting on the party.

One of the biggest days in the Golden Dawn trial came at a central Athens courtroom on November 6, when Michaloliakos was slated to take the stand, the last of the defendants to testify in their own defence. Psarras took a seat toward the front, surrounded by fellow reporters, and fired up his laptop. After the Golden Dawn chief made a dramatic entrance flanked by police officers and with his supporters standing at attention on the opposite side of the gallery, he sat at a table overlooked by three justices, the state prosecutor, and several court officials. For more than three hours, he dismissed claims that he incited and oversaw violence, blaming a cabal of elites for waging a “political conspiracy” against his party.

Sitting not far from Psarras, I watched him hardly register a reaction when the lead judge brought up the statute that had sat on his desk for months three decades ago.

Michaloliakos finished his testimony and exited the courtroom to pro-Golden Dawn chants and boos. Some of his supporters threw up fascist salutes, but anti-fascists on the other side of the auditorium out-shouted them, calling out “Pavlos lives on, smash the Nazis.”

Afterwards, I found Psarras outside the courtroom. Smiling, he told me the Golden Dawn leader’s testimony was a “disaster”.

But a conviction is far from guaranteed. Last December, prosecutor Adamantia Economou surprised many when she urged an acquittal, saying that it could not be established that Michaloliakos and senior party officials had orchestrated Fyssas’s murder. “What possible gain was there in this?” Economou said. “A murder in a central location? If Fyssas had been a target, they could have killed him somewhere out of the way.”

The about-face came as a shock for many, including Fyssas’s mother, Magda, who responded: “After all this time, is this all they understood … How much more of this can we take?”

A triumph for democratic values

Even with Golden Dawn embattled and facing potential extinction, far-right violence has continued to pick up. Last year, the Racist Violence Recording Network (RVRN) tallied 100 incidents of racist violence, more than half of them targeting refugees, migrants, and the human rights advocates working with them. In 2018, xenophobic attacks and hate crimes around the country swelled by 14 percent, according to the Athens-based RVRN’s tally.

In snap elections last July, the centre-right New Democracy party ousted Syriza, its left-wing rival. Campaigning on a stridently anti-refugee programme, New Democracy had absorbed much of Golden Dawn’s voter base, and another far-right party, Greek Solution, had clawed its way into the parliament.

Last year, refugee arrivals by land and sea reached their highest levels since the 2015 refugee crisis first erupted. Anti-refugee protests also spiked, with local officials riling up residents on some Greek islands and in villages on the mainland. To block asylum seekers from being relocated to their communities, they would storm ferries carrying refugees, or take to the streets, burn dumpsters and tyres, and try to block buses. “These incidents may be committed by small groups from local communities but the wide-spread and organized nature they seem to take, as well as the involvement of officials, are of particular concern to us,” the RVRN warned last November.

One day, Psarras hopes, historians will look back on Golden Dawn’s meteoric rise as a dark period in Greece’s modern history, and view its even quicker demise as a triumph of democratic values. Perhaps those same historians will find in Psarras’s work invaluable information. For now, however, he hopes that the trial will result in convictions.

“If the trial goes wrong,” he explains of the possibility that the party could evade conviction, “it could happen again.”