Mining Earth: From the Amazon to the ocean’s depths

We should not be asking how much more we can take from the planet, but how much more can the planet take?

It seems like another age, the days when we journalists were free to easily roam the world witnessing everything first-hand. Now, we look back even just a year ago and wonder at what we saw, and perhaps more to the point, at what we do not see now.

In September last year, I was in a helicopter, flying low over the dense forests of French Guiana. I wrote about how rainforest covers 98 percent of its territory – a carpet of biodiversity that spreads in every direction as far as the eye can see, the canopy a thousand shades of green. Every now and then you would see a glint of light reflected off the countless rivers and waterways that meander through a jungle the size of Ireland.

Keep reading

list of 4 itemsMelting glaciers, rising seas: Approaching climate tipping points

The climate crisis: Preparing for what’s already here

The US is back in the climate fight

Such intact rainforest is seemingly a rare commodity in Amazonia. But we soon realised parts were not as untouched as they first seemed. As the helicopter banked around 180 degrees, it swooped over a great scar of brown earth hewn out of the canopy below.

On the ground, little figures scattered in panic – the garimpeiros or illegal miners, looking anxiously up at us, some throwing equipment into muddy pools of water. They come to these forests in their thousands in search of a fortune. And some find it.

The rise in the price of gold in recent years has sparked a mini gold rush. There are around 400 illegal mine sites in French Guiana, employing around 7,000 people.

Around 10 tonnes of gold is extracted annually – worth an astonishing half a billion dollars and more. But the environmental toll is colossal.

“Trees are uprooted and sites left abandoned when the miners move on. The process involves mercury which leaches into the soil and waterways, polluting the rivers and the whole biosphere,” Laurent Kelle from WWF told us at the time. And once the mines are abandoned, the area remains poisoned for years.

Well, in the 12 months since my trip, things have gotten worse – and not just in Amazonia. According to a new report from the World Resources Institute (WRI), with gold prices skyrocketing, mining poses a growing threat to communities and ecosystems around the world.

“Gold prices had been rising for years but the threat to economies from the novel coronavirus led to a surge in prices – up as much as 35 percent this year – as investors sought the perceived safety of gold,” the report said.

“As the price of gold rises, so does demand and mining in the Amazon.”

In 2019 deforestation caused by garimpeiros in the Brazilian Amazon rose 23 percent from the year before, the Guardian reported; meanwhile, Brazilian gold exports rose 35 percent from January to August this year, hitting the $3bn mark.

This is not just an environmental challenge but a social one too. The WRI report found that more than 20 percent of Indigenous lands are overlapped by mining concessions and illegal mining.

In Peru, the gold rush has destroyed swaths of once-pristine forest in one of the country’s most biodiverse regions. Tens of thousands of miners, most from the poor Andean highlands, have flocked to Madre de Dios, Reuters reported. They arrive hoping to earn a living but have to evade authorities who are struggling to combat the illegal trade. Across the region, these illegal mines are also a magnet for criminals and sex traffickers.

Forest floor to seabed

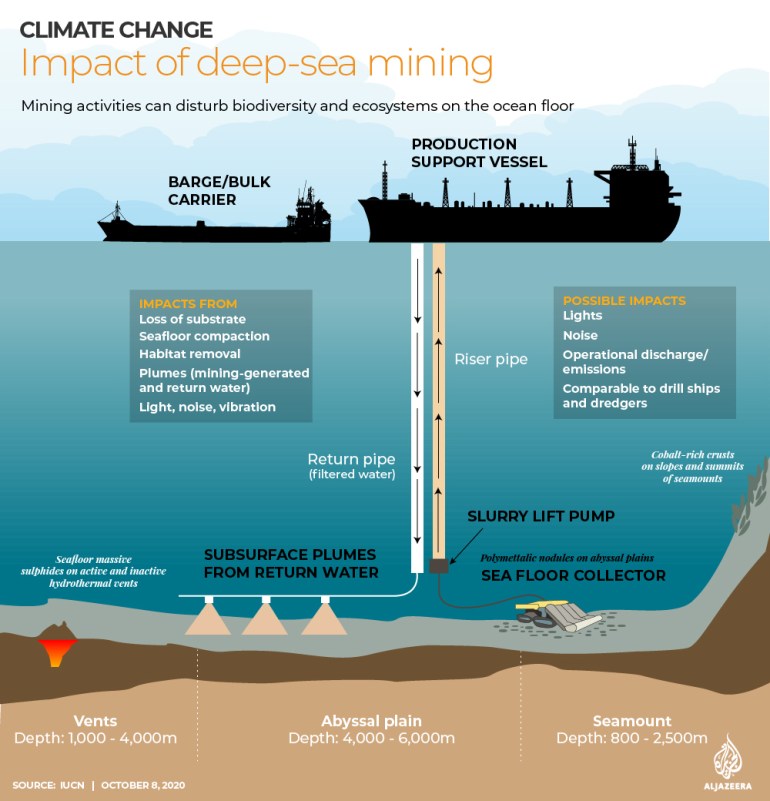

You would think that the hard-learned lessons from Amazonia would shape our approach to a new frontier: the deep ocean.

In places, the unplumbed depths are home to significant amounts of the sort of metals and minerals we need to ramp up renewable technology. For example, copper, used for wiring; lithium and cobalt for batteries; and rare earth elements for things including solar cells and electric cars.

But where some, like the EU-funded Blue Nodules Project, say mining can be achieved with minimal environmental damage, others warn against exploitation of the ocean floor.

Louisa Casson, a campaigner at Greenpeace, said it risks disturbing important carbon stores that could make climate change worse. “The deep sea is one of our best defences against climate change as sediment down there helps lock away carbon,” Casson said. “ Churning up the seabed could disrupt this natural ocean process, and lead to the release of this stored carbon into the ocean and atmosphere.”

Exploiting Earth

The race to mine the seafloor seems to be imminent. Soon projects could begin more than 200 nautical miles from shore, beyond national jurisdictions.

If we cannot effectively police surface exploitation of Earth’s resources in Amazonia and beyond, there are fears for the health and stability of the ocean depths, where submarine mining proceeds are out of sight and out of mind.

Once again, we should not be asking how much we can take from our planet, but how much more can our planet take?

Your environment round-up

1. A prize to save the planet: Britain’s Prince William is looking for solutions to repair the planet by 2030. In exchange, he will award $65 million over 10 years for the winning initiatives.

2. Hottest September: Last month was the warmest September on record, meteorologists said – it was 0.05C hotter than the same period in 2019.

3. Drug damage: We know drug trafficking and cartel wars cost human lives, but how does growing drugs – such as cannabis, coca and opium crops – affect the environment?

4. Sir David Attenborough on capitalism and nature: The excesses of capitalism need to be curbed, according to the veteran broadcaster, who says nature will flourish when “those that have a great deal, perhaps, have a little less”. Listen to the podcast.

The final word

Many eyes go through the meadow, but few see the flowers in it.