The prosecutor’s son: ‘The living legacy of Nuremberg’

Don Ferencz’s father prosecuted Nazis at Nuremberg and made sure his son understood the depths of their crimes.

On November 20, 1945, several months after the end of World War II, a series of military tribunals began in the German city of Nuremberg.

The first of the trials was the Major War Crimes Trial, in which 24 high-ranking Nazis stood trial in the Palace of Justice. Twelve of the defendants would be sentenced to death.

A further 12 trials – known as the Subsequent Nuremberg Proceedings – were held at Nuremberg between 1946 and 1949.

Keep reading

list of 4 itemsThe survivor’s silence: Remembering the Nuremberg trials

The man behind ‘the biggest murder trial in history’

We need to rethink the concept of genocide

Seventy-five years after the Nuremberg trials began, we hear from three people upon whose lives the trials and the events that proceeded them cast a long shadow: the son of one of those on trial, the son of one of the prosecutors and the daughter of a Holocaust survivor.

Don Ferencz is the convenor of The Global Institute for the Prevention of Aggression. His father, Benjamin Ferencz, is the last surviving Nuremberg prosecutor. Ben was 27 years old when he became the chief prosecutor in the Einsatzgruppen Trial – the ninth of the 12 Subsequent Nuremberg Proceedings. In it, 24 commanders of the mobile death squads that operated in Nazi-occupied Eastern Europe stood trial for war crimes and crimes against humanity.

Here, Don Ferencz describes what it was like to grow up in the shadow of the Nuremberg trials:

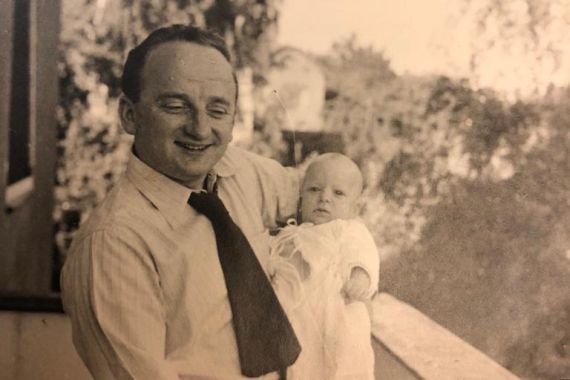

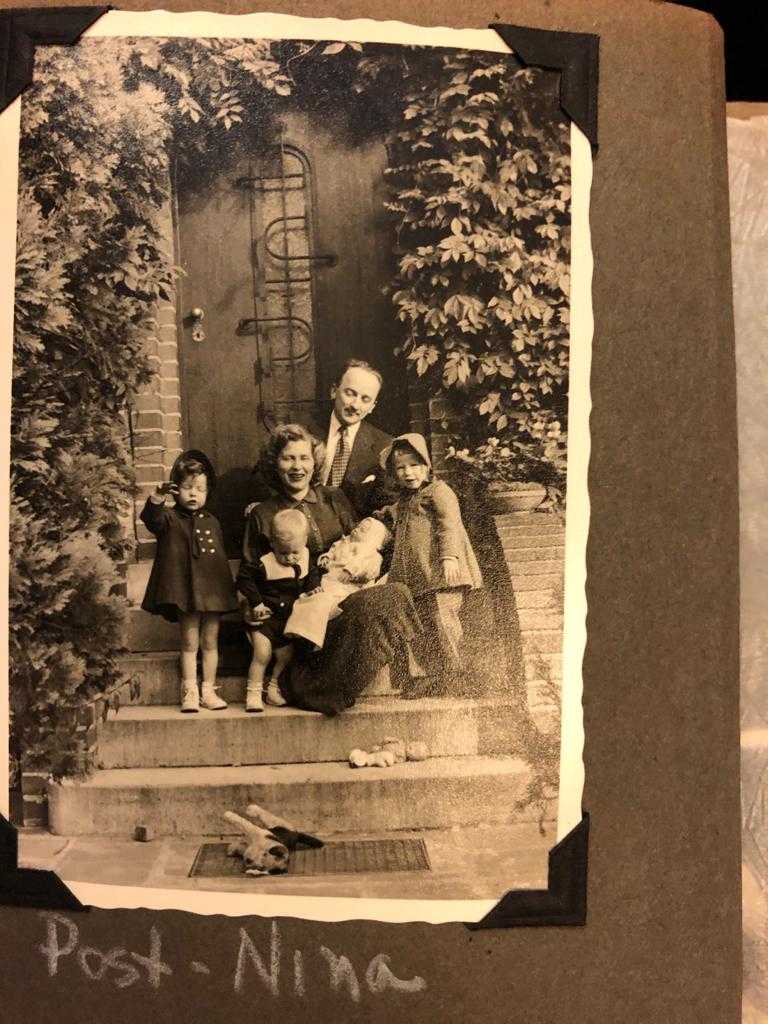

I was born in Nuremberg in 1952, but was no older than four when my family left Germany for the US, so have very little recollection of the country.

My father was a witness to the Holocaust. As a member of the US army stationed in Germany he joined General George S Patton’s war crimes branch that liberated and investigated Buchenwald, Mauthausen and Flossenburg concentration camps.

My dad was traumatised by what he saw there, but he did not hold subsequent generations of Germans accountable for the sins of their fathers. He recognised that the crimes were committed by people, not nations.

Still, my dad told us in no uncertain terms what it would have been like for us as Jewish children living in Hitler’s Germany. He said the Nazis would have smashed our heads against the wall and thrown us out of the window. He told us all these stories; horrific stories that you should never tell a child of that age. I didn’t understand why he did that.

I remember very vividly that my father had a box he kept in his closet beneath his clothes. Inside it were horrible, gruesome photos. It might have been that he tried to instil an awareness and understanding of what happened there in his children as a way of coping with his own PTSD. Perhaps it was his way of making sure that we would always remain vigilant.

I grew up with the belief that aggressive war is a crime against the peace and security of the whole world. At Nuremberg, the American chief prosecutor, Robert Jackson, explained that leaders who “set in motion evils which leave no home in the world untouched” should be held to account in a court of law, and I truly believe that.

Growing up, I was very proud of my father and the fact that he was a prosecutor at Nuremberg.

I idolised him and recall how, as a child, I put together a scrapbook of articles and newspaper clippings about him. He tried to teach us how to be ethical, considerate, thoughtful people.

In 1996, we established the Planethood Foundation together with the aim of “educating to replace the law of force with the force of law”.

It was never troublesome for me to be his son. When I started working in the international criminal justice community, I had a card with the name of our foundation and my name on it. Invariably the people I gave the card to would say: “Are you related to Ben Ferencz?” So much so that I changed the card so that under my name, it said “Yes I’m his son!” If I didn’t have any cards with me, I would tell them (and I often still do) that “my mother swears it!”

From 2005 to 2017, I was involved with the International Criminal Court’s (ICC) effort to activate its jurisdiction over the crime of aggression. I helped organise a virtual working group of professionals called the Global Institute for the Prevention of Aggression, which was active in the effort to achieve the 30 ratifications necessary for the Kampala amendments to the ICC Statute on the crime of aggression to be activated, which we achieved in 2017.

I have lectured on the crime of aggression in many places including Mexico, the US, Ireland, the UK, Germany, Italy, France, the Netherlands, China, Croatia, South Africa, India and Senegal.

Nuremberg was sometimes called “victor’s justice”. But I would like to focus attention on something Chief Prosecutor Robert Jackson said at Nuremberg: “Wars are started only in the confidence that they can be won.” What Nuremberg and the core crimes – crimes against humanity, genocide, war crimes and crimes of aggression – are intended to create is a system of laws that apply not only to the losers in a war but also to the victors.

I only returned to Nuremberg in the 1990s for an academic event on the International Criminal Court. It felt like visiting a new city for the first time. I didn’t return to the house I was born in and it didn’t feel like revisiting a place from my childhood. But having been born there, I feel that I am, quite literally, part of the living legacy of Nuremberg.