An American comes home, voting with gratitude

Casting a vote at home after decades abroad reminds me what a privilege it is to have a voice in government.

My mail-in ballot had been sitting on a table for a couple of weeks before I finally had time to do a little research on the lesser-known names (to me) of the local officials on the ballot, and complete it.

I carefully followed the directions, putting it in its privacy sleeve, signing, dating and sealing it exactly as instructed.

Keep reading

list of 4 itemsWill mail-in voting affect US election night results?

US Elections: Reporting in a Pandemic

How the COVID-19 pandemic has changed the US election

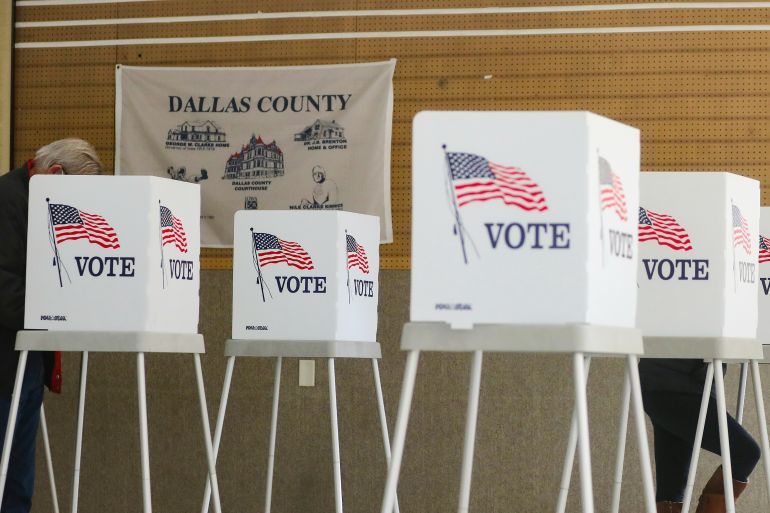

Then, because I had left it so late, I drove to the local library, an early voting station with a ballot drop-off box. It was easy to find, as there were political signs planted in the grass around the building – all the mandated 3m (100 feet) from the entrance. There were people too, brandishing signs and handing out stickers. They smiled and waved to me as I drove into the parking lot.

I took my ballot to a box outside the door. Two women were there, masked, bottles of hand sanitiser in front of them.

“Did you sign it?” they asked me as I pulled my envelope out of my bag.

“I did,” I nodded. I knew unsigned ballots made them ineligible for counting.

“Ok then, put it in,” said one.

I dropped my envelope into the box.

“Congratulations, you just voted,” the woman told me.

“Thank you,” I replied and quickly turned. I had wanted to say thank you for being here – to express my appreciation to all the poll workers enabling this process. But I was suddenly, inexplicably overcome with emotion. I had barely made it back to my car before I started crying.

My thoughts swirled. I felt guilt and gratitude at the ease of the process, knowing there are many communities, particularly those that are home to people of colour and minorities, where it will not be so easy to vote – where there will be long lines, or a long drive, or restrictions put on mail-in ballots that make voting more difficult and onerous.

My first vote on United States soil in two decades made me feel proud to be an American, taking part in our greatest privilege as citizens. And maybe for the first time, I felt like I was really home.

I returned to the US this spring after living abroad since 1993, most recently spending eight years in Afghanistan, where my dog and cat remain stranded (but that is another story for another day).

I watched last year as Afghan election officials, poll workers and voters were attacked, threatened and killed by the Taliban, opposed to a popular vote, even as its leaders negotiated a withdrawal of US troops in an accord that has done nothing to stop violence against Afghans.

In my years abroad I have witnessed a number of elections – the chaotic Russian parliamentary vote in the heady days of 1995, when dozens of new political parties in the free-for-all that was post-Soviet Russia vied for the 450 seats in the Duma, including the centrist Our Home – Russia, which came second to the Communist Party, and the Beer Lovers party, which won no seats.

A year later, Russian incumbent President Boris Yeltsin would hire US Republican strategists to help in his re-election campaign.

The 1997 election in Kenya is forever etched into my memory. Kenyans lined up for hours as voting stretched into a second day. In one Nairobi neighbourhood, Kenyan observers watched like hawks as the votes were counted twice. When the result was not the one the dominant party in the area wanted, polling officials threw the observers out, “recounted” and suddenly the “correct” winner was ahead. For me it was a shock to see such blatant vote-rigging with people watching – an introduction to officials who did not care about the people’s will.

The voter turnout wasn’t clear in Bosnia’s first post-war elections in 1996. The Organization for Security and Co-operation in Europe (OSCE), which oversaw the vote, didn’t know what the voting population was and the NGO the International Crisis Group approximated turnout was above 100 percent – impressive after a war that had killed an estimated 100,000 people and displaced 2.2 million more.

And now I have returned to cover elections in my home country, saddened by the deep divisions that appear to be everywhere.

Millions of Americans will not be able to vote, or their votes will not be counted, like the hundreds of thousands of former felons in Florida, where in a 2018 referendum the people overwhelmingly voted to restore their voting rights in a 65.55 percent to 34.45 percent contest. The Republican-led Senate and governor passed a law requiring that in order to vote, former felons must pay “all fines and fees” associated with their convictions, without any mechanism to determine exactly what those fees are.

Like everyone else, I have no idea who will win this American election but like so many I am hoping it will be peaceful. It has been a privilege to vote and it is an honour to be reporting on the process, hearing the voices of so many American voters, and spelling out the issues on their minds.