Meet the women behind the Indian farmers’ protests

In India, the land is ‘mother’; and it is India’s mothers, daughters and sisters forming the backbone of the protests.

Baljit Kaur, 50 has been farming most of her life in Punjab, India. For her, cultivating her crops and tending to the land is a blessing and goes beyond simply being a profession – it is in her blood.

On a normal day, Baljit would be spending long hours in the fields, carefully sowing her seeds and preparing for the harvest. The work is not easy, but she is dedicated to it. Today, however, she is not in her fields – she is on the outskirts of the Indian capital New Delhi at the Tikri border, where she and many other farmers – female and male – have travelled for hundreds of kilometres to protest against new farming laws passed in September.

Keep reading

list of 4 itemsIndia farmers vow to intensify protests, reject gov’t talks offer

In Pictures: Angry India farmers march against ‘pro-market’ laws

India farmer protests: Has PM Narendra Modi gone too far?

“We are protesting for our land, against the kali kanoon [black law] that Modi has introduced,” Baljit says. She fears the new laws will jeopardise the ownership of land that has remained in her family for generations, and she is determined to set this right.

The farmers worry that the three laws, designed to deregulate the agricultural sector, do not include a Minimum Support Price (MSP), a minimum price guaranteed by the government at which farmers can sell their crops. Without this safety net, farmers fear they will have to participate in contract farming with private corporations, where these companies determine what the farmer grows and the price they sell at. The laws also remove restrictions on companies buying land and stockpiling goods.

While Prime Minister Narendra Modi argues that these laws will modernise the agricultural sector, farmers insist that without a guarantee of an MSP, opening the market to contract farming and mass privatisation will pave the way for exploitation of already vulnerable groups.

The protests against these new laws have gained momentum over the past few weeks. Hundreds of thousands of protesters have marched from the three main farming states of Punjab, Haryana and Uttar Pradesh to set up camp at Delhi’s Singhu and Tikri borders, main entry points to the nation’s capital.

Despite officials’ attempts to deter protesters from entering the city, the farmers’ agitation shows no signs of abating. Their demands are simple: repeal the laws.

‘Women work harder than the men’

While men dominate the public image of the farmers protesting in India, women are very much there as well. In fact, female farmers will be among some of the worst affected by the new laws.

According to Mahila Kisan Adhikaar Manch (MAKAAM), an Indian forum that campaigns for the rights of female farmers, 75 percent of all farm work is conducted by women yet they own only 12 percent of the land.

Kavitha Kuruganti of MAKAAM says the lack of land ownership makes female farmers “invisible”. Without land, they are not recognised as farmers despite their large contributions to the sector and this marginalisation means they are especially vulnerable to exploitation by large corporations under the new laws.

The lack of safeguards from the government for pricing will widen the gender gap in farming as the premise of “increasing competition” assumes women are able to trade as easily as men when they are subject to greater limitations, such as accessibility to transport and being responsible for duties at home, for example.

Kulwinder Kaur and Parminder Kaur (Kaur is a surname given to all Sikh women) are two female farmers who have made the 645km (400-mile) trip from Jalandhar, Punjab to Tikri. They set up camp in the trailer of a parked truck where they are sitting with other female protesters when they speak to Al Jazeera.

“When there isn’t going to be a fixed rate or mandi [market], how will we feed our children rotis [bread] and how will we sell?” Kulwinder asks.

Parminder adds: “No work is easy, you have to work to eat. But if even after working we still can’t eat, then that’s really wrong.”

They worry the introduction of these laws will mean working for large companies with little to show for their hard work, as both women argue large corporations essentially “steal” from the farmers to sell their crops at prices often four times higher in the city.

Mulkeet Kaur, 60, who has been farming for the past 30 years argues that, in her village in Punjab, plenty of women work in farming and work even harder than the men.

Even in the context of the protests, the women who stayed behind to look after families and farms are making an invaluable contribution to the protests, as much as the women standing alongside their male counterparts in the cold and unsanitary conditions of Delhi’s border towns.

Mulkeet has travelled to the Singhu border to protest on the front line, as she worries that the lack of a guarantee of an MSP will affect her income.

“If they lower the prices of our crops, where will we go?”

Despite her fears, Mulkeet is hopeful that the laws will be repealed and calls on her faith to keep her resolve. “I hope God listens to us; we’ve come all this way”. While Mulkeet will be leaving the next day, she says someone from her family will be taking her place. The protesters are in it for the long haul.

‘Life is not worth living if our children suffer’

For many older female farmers across India, the issue of land ownership goes beyond the financial. Land is sacred and ownership is generational, rooted in a rich ancestry and culture.

“What will our future generations say, that we didn’t raise our voice?” Baljit asks. “That’s why we are sitting on the street, to save our land for our grandsons.”

This forward-thinking mindset is common among the older women sitting in protest at both Tikri and Singhu borders.

Jaspal Kaur, 58, is sitting on the ground at Tikri border with two other female protesters, her and one other wearing matching “basanti dupatta” (yellow scarves) to “keep the spirits of the martyrs like Bhagat Singh alive”, she says.

Jaspal travelled from Punjab to Tikri with her husband because she believes the laws will be detrimental to future generations, calling them an attempt to “steal our grandparents’ earnings”. “Life is not worth living if our children will suffer,” she says.

Her words take on greater significance considering that more than 10,000 Indian farmers took their own lives in 2019 following the poor conditions and debt generated from farming.

“We will move forward with the men, shoulder-to-shoulder. We will have to bear the hardships,” Jaspal says in a voice that never falters.

The farmers are one and the winter months can be borne when their culture is built upon supporting one another, they say.

Communal kitchens and selfless service

There is a community spirit at the protest sites as women and men sing revolutionary songs, dance and perform street theatre.

Jassi Sangha, 33, is a self-proclaimed “proud daughter of farmers” and filmmaker who has been documenting the protests in Delhi. In one song she posted, women are proclaiming: “These women are here to fight the state. So, you will have to salute the resilience of these women and you will have to give them space.”

Langars (communal free kitchens) have been set up across multiple protest sites, based on the Sikh act of selfless service (seva). Jassi explains: “Protesters brought rations for several weeks, so much that even the locals are having their meals from our langars.”

Sonia Mann, an actress and social activist from Punjab, also came to protest alongside the farmers. “I’m a daughter of kissan [farmer],” she says. “My father was a union leader and he sacrificed his life for the sake of farmers, which is why I’m in this moment.”

Sonia, 30, is clear about how damaging these laws will be for smaller farmers, including landless women: “They [big corporations] all want to acquire our lands and open their corporate houses there. So, they just want to finish Punjab.”

While the movement began in Punjab, the protesters’ message is that this is not an issue restricted to Punjab but one that impacts all farmers and will have national repercussions. For these protesters, it is a fight that transcends religion and state borders.

“The farmers from Haryana, Rajasthan and other states are involved in this protest,” Sonia says. “They all come together and take decisions together. They respect everyone. There’s always a Hindu, Muslim, Sikh; everyone comes here.”

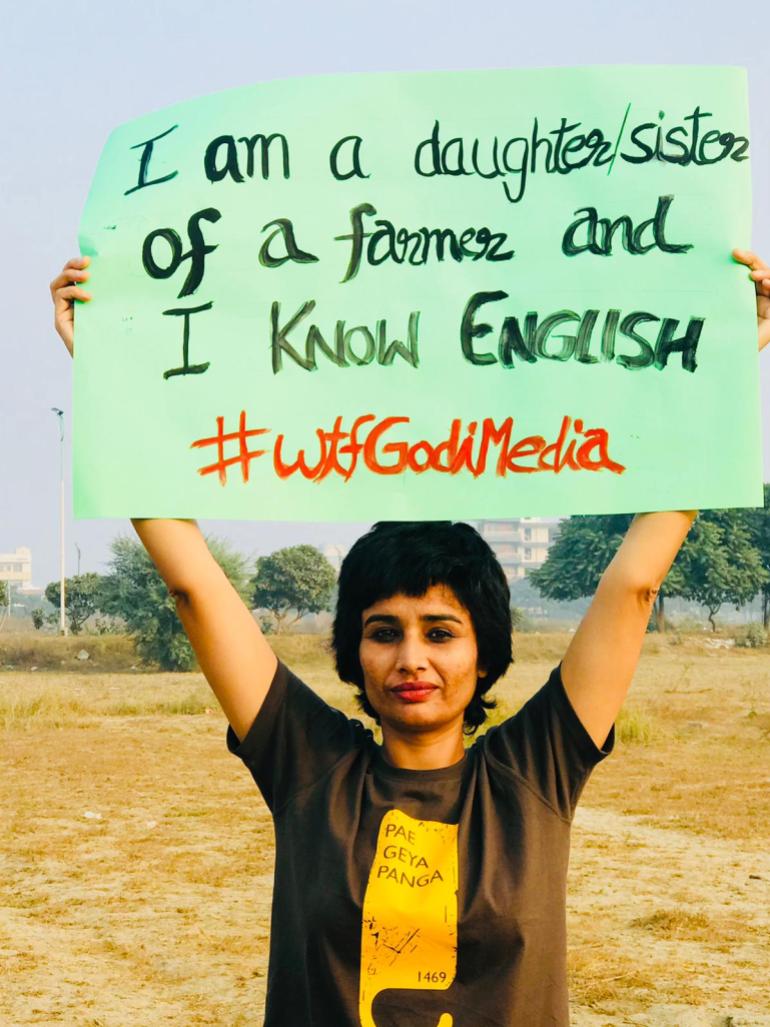

Tear gas and water cannon

Rhetoric from India’s ruling Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP) paints the protesting farmers as “anti-nationals” and some have gone as far as to call them “terrorists”.

“They just want to spoil our protest,” Sonia says. She believes the government and media are attempting to misconstrue the message of the protest as a religious and anti-national one.

While the protesters are angry and determined, they are also cautious and patient, and very careful about who they allow to speak on their behalf. Any mention of “Khalistan” [a Sikh separatist movement] could dangerously impact their agenda and give the media and government an opportunity to misinterpret the protests, they say.

“Having opinions is not being anti-national, having opinions does not make them wrong,” says Nikita Jain, a journalist covering the protests on the ground. She points out the irony of these accusations: “How can you call our own farmers, who are the biggest nationalists, anti-national?”

Jain emphasises how peaceful the protests are and the injustice of how the farmers have been treated despite the kindness they have shown. “The vibrations are beautiful there.”

Despite this, tear gas and water cannon have been used on peaceful protesters, including elderly protesters. Jassi says: “India is known as the world’s largest democracy, and what happened during this peaceful protest was an utter human rights violation.”

Jain describes what she witnessed on November 26, when the protesters attempted to peacefully enter Delhi but were met with brutality from the police. “People have the right to protest,” she argues. “That doesn’t mean the government beats them.”

‘We have our knee on their neck’

According to police, there have been at least 25 deaths during the protests caused by cardiac arrest, hypothermia or road accidents because of the protesters’ poor conditions.

Many sleep on the ground or in the back of trucks and rely on the kindness of locals to allow them to use toilets – using the outdoors where no facilities can be found. But this has not deterred the women farmers.

A sixth round of talks between farmers’ union leaders and government officials was cancelled last week after there was no agreement on the revocation of the laws. But the farmers’ demands continue to reverberate around Delhi’s borders and their will is strong, they say.

It had rained the day before Baljit and Jaspal spoke to Al Jazeera, but neither woman complains about the cold or discomfort.

Despite the deadlock between the government and the farmers, the female protesters have hunkered down and are prepared to wait until their demands are met.

Parminder and Kulwinder are equally stoical. “We have been here since this started. We will stay here. There’s no problem; we are not missing home,” says Parminder, her voice steady and her face defiant.

The women are feeling the support from back home, as Kulwinder explains: “They are phoning after us and saying: ‘Be strong, don’t give up’.”

When questioned about how successful their efforts will be, both Parminder and Kulwinder agree, the defiance laced through their words: “Why would they not take it back [the new laws] when we have our knee on their neck?”

Jassi explains how for many farmers, “the land is Mother”, and it is India’s mothers, sisters and daughters who are forming the backbone of this protest.

The farmers’ agitation is set to continue. As Baljit says, “we have raised our voices and we are going to take our rights.”