The front-line heroes of the pandemic: Young carers

Life for children tasked with caring for sick or disabled relatives has become significantly tougher during the pandemic, with much of their work going unseen and unacknowledged.

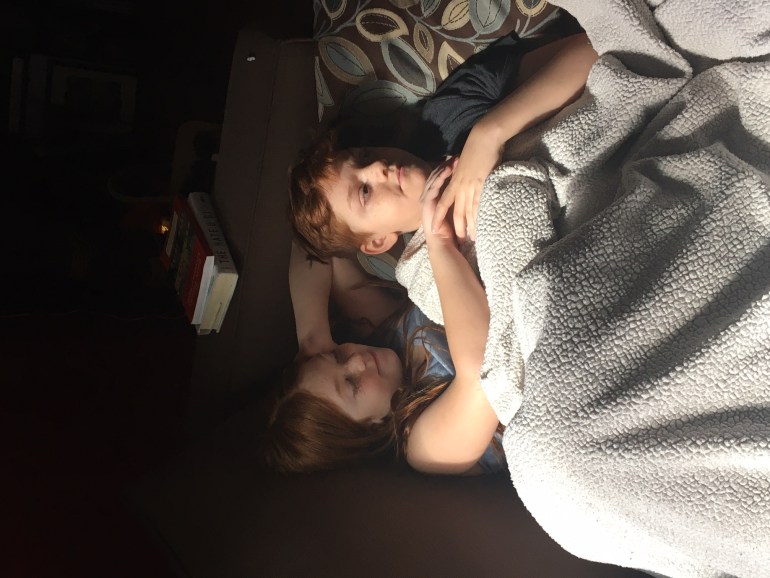

Every morning when nine-year-old Willow Kemp, from Toronto, wakes up, she hears the sound of her brother, Hunter, calling out for her. She pads along the corridor to his bedroom for “snuggles”, doing her best to lift his spirits if he is having a high-pain day.

After surviving childhood leukaemia, Hunter, 13, has been left suffering from debilitating, chronic pain that often leaves him bedbound. Despite being four years older than Willow, Hunter has nicknamed his little sister “mini-mom” because of the caring role she has taken on in his life. Although their mother, Sitara, 47, is Hunter’s primary carer, Willow helps her brother with everything from medication to fetching him what he needs, massages during episodes of chronic pain, and extensive emotional support.

Keep reading

list of 4 itemsUK dementia patients face challenges during lockdown

Are we seeing light at the end of the tunnel for coronavirus?

Sleep-in carers should get minimum wage, top UK court told

“I’m the little sister but sometimes it feels like I’m the big sister,” says Willow. “Hunter has to go to hospital a lot and he likes me to go with him because it makes him feel better.”

The pandemic has changed all this. “Now I can’t go with him. One time he went and it was really scary at the hospital and he hated it. When he came home, he was yelling my name and trying to find me so I rushed to give him a big hug.”

Willow is one of Canada’s estimated one million young carers – aged under 25 – who spend a significant amount of time caring for a family member with a disability, health condition or mental health disorder. There is no data about the total number of young carers globally, and statistics for individual countries are sketchy because governments of most states simply do not collect them, underlining the fact that the work of child carers the world over goes largely unacknowledged.

The country-by-country figures that do exist are mostly for Western countries, and they are stark: in the UK, there are an estimated 700,000 young carers; in the US, the figure is more than one million; while Australia has at least 235,000. The duties of these young carers vary by household but can include practical care such as cooking and cleaning, personal care such as helping a family member wash, dress or go to the bathroom, as well as emotional support.

Lockdown has been especially tough for many young carers, as access to support services has dwindled or stopped altogether. In the UK – the country with the most extensive data on caring – 58 percent of young carers say they are spending at least 10 hours more per week on their caring duties during the pandemic, 11 percent reported an increase of 30 hours, while nearly 8 percent are now spending 90 hours a week caring for a family member. Many families have found themselves cut off from extended family or friends who normally provide support and are faced with the additional challenge of juggling working or studying from home with increased care duties.

Although Willow initially “quite enjoyed” the novelty of lockdown, the honeymoon period soon ended as the additional burdens that came from so much time spent at home began to grow. An estimated 68 percent of children with a disabled sibling have taken on additional caring during lockdown. “Being at home so much, I do help with Hunter a lot more because I’m with him all the time,” she says. “I miss school because normally it can be a chance to kind of not worry about Hunter and do my own thing and not think about things too much at home. But I will always look after Hunter, even when we’re grown up.”

‘Another lockdown would kill me’

Willow and Hunter attended the same school until four years ago when it became apparent that Willow, aged just five, was using her bathroom breaks to check on her brother. “She had internalised school as her ‘shift’, as I was off the clock, and she felt it was her duty to watch out for him,” says Sitara. “There was one day when Hunter left early and when she went to check on him, she got very, very scared because he was no longer there. She thought something terrible had happened to him. That’s when I knew I needed to send them to separate schools.”

Willow and Hunter are so close, they have developed a secret language and complex make-believe worlds that not even their parents can understand. Willow has developed a series of massage techniques to help ease her brother’s pain, giving her soothing moves nicknames such as “candy chops” and “sushi making” to mimic the gestures.

In Canberra, Australia, Rita El Khory, 19, has faced a whole host of challenges as she attempts to juggle university studies with caring for her brother, Johnny, 17. Rita has been helping to care for her brother for as long as she can remember, but her role stepped up significantly when her parents separated when she was 14. Johnny has a severe intellectual impairment and has the mental function of a toddler. He cannot dress or feed himself and requires round-the-clock supervision, as well as regular nappy changes.

“It was really hard for Johnny to understand what lockdown was, so he became a lot more full-on and sometimes even aggressive,” says Rita, who is studying to be a social worker. “Being at home, I wasn’t able to escape to uni or my Muay Thai training – things that normally keep me sane. Johnny’s carer couldn’t come in and my grandparents weren’t able to help out like they normally do, so it was just me and mum, both of us trying to juggle work and study. We would take it in turns. Sometimes I found myself sitting in my car, parked in my garage to try to get some school work in. Otherwise, Johnny would always be there.”

Rita spends at least five hours a day caring for Johnny and even more on the weekends, a schedule she has had for much of her life. “My mum has always felt guilty about how much I do,” says Rita, “but it’s nobody’s fault. I’m her rock and she relies on me, and I’d do anything for Johnny. But another lockdown would kill me, it honestly would. I felt like I was suffocating.”

Willow’s mum, Sitara, is careful to make sure her duties don’t become overwhelming. “I constantly check myself to make sure she’s not doing too much,” she says. “Because she’s so mature and she’s so willing and eager to help, I have to teach her to recognise that she’s not just a kind person, she’s actively working as a carer, which means she needs to take a break.”

For the past four years – since she was just five years old – Willow has been attending the Young Carers Program (YCP) in Toronto. The programme focuses on teaching children skills for coping with stress, such as mindfulness, as well as practical lessons in cookery and medical education. Soon after lockdown started in March, YCP switched to an online programme. Twice a day since then, Willow has logged on like clockwork. “That time became gold,” says Sitara. “She really wanted her space but was not always able to articulate that. Just having that time for herself meant a lot. Hunter actually got jealous she was spending too much time with YCP and not enough time with him.”

Diagnosed with anxiety at the age of 10

Globally, support systems such as YCP aren’t widely available and often rely on goodwill for funding. But for the young carers who are able to access them, they can prove a lifeline, particularly when it comes to mental health support. Over a third of young carers suffer from a mental health condition, while a recent study by the Carers Trust in the UK showed that 40 percent of young carers have suffered from worsened mental health during the pandemic.

Rita was diagnosed with generalised anxiety disorder at the age of 10 and has struggled with panic attacks and insomnia for much of her life. “I was actually feeling a lot better for the last couple of years,” she says. “But in lockdown, my anxiety flared up badly and I was feeling pretty down much of the time.”

For Jenna Nelson, who manages the YCP in Toronto, providing young carers with coping strategies is key. “We can’t take their caregiving role away and we can’t change their circumstances at home, but we can make that easier on them by teaching them strategies and self-care, as well as advocating for additional support, so that they have the resources in place to hopefully not end up experiencing larger mental health concerns.”

Willow has found YCP calls an enormous support during Canada’s two lockdowns. “I have a constant worry, it’s sort of always there,” says Willow. “Sometimes it can get bigger, but sometimes it’s smaller too. If I do a YCP call when I’m feeling bad, that has taught me to centre myself and it helps me feel better afterwards.”

Despite the challenges that come with being a young carer, supporting a family member can also bring a sense of self-worth. In Canada, 78 percent of young caregivers say they find caregiving very rewarding. “There has been some evidence that it’s not all terrible – children can take pride from caring as well,” says Lucie Cluver, a professor of Child and Family Social Work at Oxford University in the UK. “It’s easy to say everything’s awful, but children can feel that they are an important part of the household and we should recognise that too, alongside ensuring they have support.”

Rita agrees: “I feel like being a young carer is actually a gift. It gives you such a special quality and I feel like Johnny has made me a better person. Caring is the most selfless thing you could ever do, because you do it for the love of the person.”

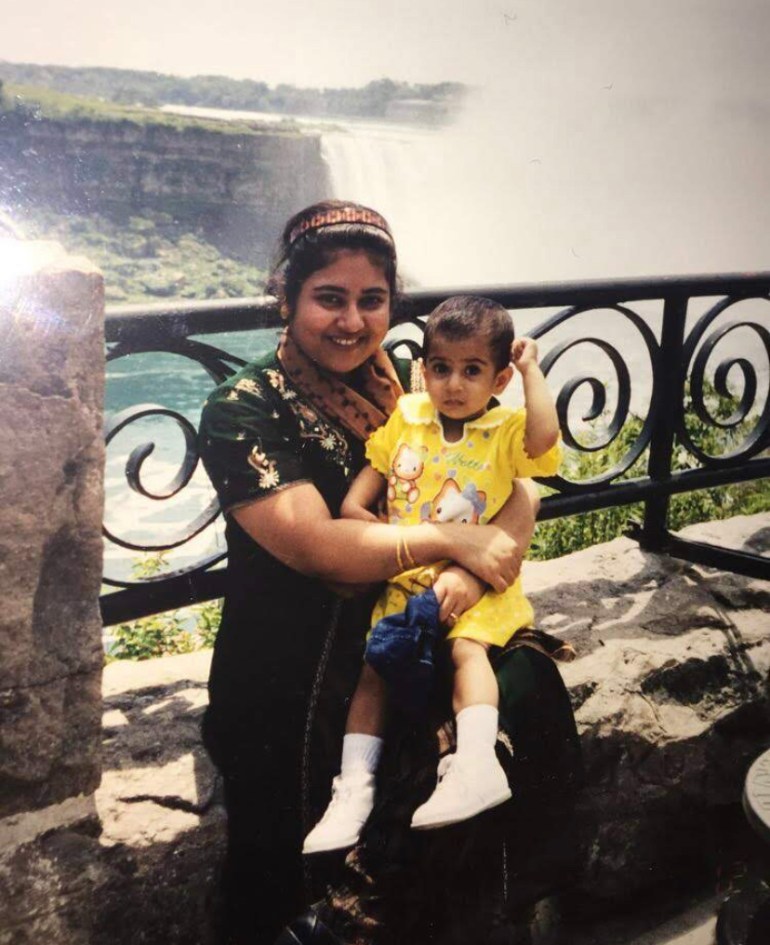

Taking on so much responsibility from a young age means that many young carers are mature beyond their years. “Being a young carer genuinely does change you as a person,” says Samiha Rahman, 18, who has been caring for her terminally ill mother for much of the past six years. “I had to grow up earlier than my friends around me and I get told a lot that I’m very mature for my age. It makes you more resilient, as well – just going on with life even though you had such a hard thing thrown at you as a young person.”

But these added responsibilities can also leave young carers feeling overwhelmed or unable to ask for help. “One of the things that we hear a lot is ‘I have to be the strong one in the family, I have to carry all these emotions’,” says Nelson. “There’s often a guilt that they’re the able-bodied person in the family, or they don’t want to complain about their circumstances because they see that someone in their family has higher needs.”

The psychological burden

As the pandemic rumbles on, caring responsibilities continue to grow and evolve as families find themselves under increasing pressure. With a global crisis in care homes, more families will be re-shifting their living arrangements to adapt to intergenerational living.

“There’s certainly likely to be an increase in the number of young people providing substantial unpaid care and support as a result of the pandemic,” says Dr Vivian Stamatopoulos, Associate Teaching Professor at the University of Ontario, whose research focuses on young carers. “We’ve seen cutbacks in hospitals, we’ve seen cutbacks in home care, and in community services. Globally, we’ve seen so many outbreaks of coronavirus in residential care homes, many families are going to try to avoid them at all costs. Grandparents and disabled family members may well be moving into family homes. There are benefits that come with that, but there’s going to be a lot of labour to pick up on.”

While young carers in Western countries have faced extraordinary struggles during the pandemic, those in developing countries have had further challenges to contend with.

“We already know that there’s increased rates of tension and stress in any family where there’s a young carer,” says Cluver, who has spent years researching the plight of young carers in African countries. “But those burdens become even greater because they are exhausted, stressed and trapped in a very small space with little opportunity to engage with the outside world. In Africa, the physical burden is clearly much higher. In high-income countries we see much more availability of basic care services – the government will usually pay for someone to come in and wash an unwell adult, whereas in Africa and low- and middle-income countries, children take on the physical burden of care. But what we see universally, whichever country we’re talking about, is the psychological burden – the worry and the enormous responsibility that young carers take upon themselves.”

For many young carers, a fear of stigmatisation can compound their stress. In the UK, 68 percent of young carers say they have been bullied because of their caring role. Many attempt to keep their role a secret from their friends and teachers – in fact, 64 percent of teachers are unaware how many caregivers they have in their classrooms.

“Young carers are often too scared to tell people what their home life is like in case someone calls social services,” says Dr Stamatopoulos. “In some cases, children who act as carers have been taken away from their families, so there’s a very real fear. Family members may say, ‘Don’t talk about this to your teachers or your friends,’ because they are fearful of an official intervention if it appears they aren’t able to take care of their children.”

Even before the pandemic, feelings of isolation were common among young carers, with 89 percent suffering with feelings of loneliness. Samiha believes her experience caring for her mother would have felt less isolating had there been a greater understanding of what it means to be a young carer. “I used to avoid speaking about it because people often don’t really know what a young carer is. I remember once in ninth grade, a teacher saying something about my mum ‘cooking up a storm’ for Thanksgiving, and I just kept quiet. I didn’t want to say ‘actually, I care for my mum’. I wish people would just know what a young carer was automatically, without me having to explain my whole life story every time.”