Benjamin Ferencz: The last surviving Nuremberg prosecutor

At 27, he took on the Nazis in the courtroom at Nuremberg and has been fighting for justice ever since.

It seems fitting that the last living Nuremberg prosecutor, Benjamin Ferencz – who turns 100 today – was born in the year that the League of Nations was founded and the Treaty of Versailles went into effect.

The former was a harbinger of the larger goals of Ferencz’s life’s work – establishing a lasting framework for international peace and justice. And the latter unleashed the historical forces that led to the rise of Nazism – the crimes of which Ferenczwould prosecute at the Nuremberg Trials.

Keep reading

list of 4 items‘Regime machinery operating efficiently’ as Tunisia cracks down on dissent

Why Egypt backed South Africa’s genocide case against Israel in the ICJ

US sanctions two RSF commanders as fighting escalates in Sudan’s Darfur

Ferencz was born on March 11, 1920, in a tiny cottage rented to his poor Jewish parents.

Just two years before, his birthplace had been part of Hungary, where Jewish residents had largely lived in harmony with their non-Jewish neighbours.

But following its defeat in World War I (1914-1918), Hungary ceded the territory to Romania, where anti-Semitism flourished.

Before Ferencz turned one, his family had fled anti-Semitic persecution, boarding a boat for the United States.

A childhood in Hell’s Kitchen

When the impoverished family arrived in New York City, Ferencz’s father, a one-eyed cobbler, had difficulty finding work. So they moved into the dank cellar of a tenement house in Hell’s Kitchen, one of the nation’s poorest and most crime-ridden neighbourhoods.

Surrounded by thieves, gangs and violent criminals during his youth, Ferencz gravitated towards a career in law enforcement. He would eventually become what Richard Goldstone, the former chief prosecutor of the United Nations International Criminal Tribunals for the former Yugoslavia and Rwanda, would later call “the heart and soul of international criminal justice”.

But his path towards a pioneering career in war crimes prosecution and peace advocacy was not immediately clear.

Elementary schools looked at the young Ferencz’s physical stature (as an adult, he barely reached 5’2″) and thought he was too small to enrol. It did not help, either, that the only languages he spoke fluently were Yiddish and Hungarian.

Eventually, though, he got into school and proved to be a brilliant student. He was transferred to an academy for gifted children before studying sociology and criminal justice at the City College of New York. From there, he received a scholarship to Harvard, where he started in the Autumn of 1940.

At Harvard, he volunteered to work as a research assistant for Professor Sheldon Glueck, who was writing a book called War Criminals: Their Prosecution and Punishment (1944) on war crimes committed by the Axis powers in World War II (1939-1945), which was then raging in Europe.

It was through this work that Ferencz began to develop an expertise in the burgeoning area of war crimes law.

Following the bombing of Pearl Harbour on December 7, 1941 – and the US’s subsequent entry into the war – Ferencz tried to enlist in the US Air Force. He was rejected because of his height. His efforts to enlist in other branches of the military also came to nought.

A witness to the Holocaust

Ferencz graduated from Harvard in 1943 and was finally inducted into an artillery battalion of the US army.

Arriving in Europe in December of that year, he found himself at some of the most significant American battlefields of the war, including the landing beaches of Normandy, the frozen forests of the Battle of the Bulge, and the parapets of the Siegfried Line.

By the end of 1944, it was clear that the Germans had been committing egregious and large-scale war crimes. When General George S Patton’s Third Army established a war crimes investigative unit, Ferencz was transferred to it.

As part of this unit, Ferencz helped liberate and investigate the Buchenwald, Mauthausen and Flossenburg concentration camps, among others. He witnessed scenes that would haunt him for the rest of his life: bodies piled up before the crematoria and skeletal human beings barely clinging to life.

“There was no time for emotion. No time for being shocked, for tears – for anything like that,” said Ferencz in the 2018 documentary Prosecuting Evil.

His son, Don Ferencz, says the horrors of the concentration camps traumatised him.

“My dad is a guy who has been traumatised by what he saw, smelt and felt with his own eyes, ears and hands,” he told the documentary makers.

“I read a number of letters he wrote while he was liberating the camps, what he saw and what he felt. This has fuelled a nuclear reaction inside this man and it’s still what he does every day.”

Ferencz was honourably discharged from the army in December 1945, having earned five battle stars, and returned to New York, where he married his wife Gertrude on March 31, 1946.

A chance encounter

Not long before Ferencz’s discharge, the Allies had begun prosecuting major Nazi war criminals before the International Military Tribunal in Nuremberg. This was the first of the famous Nuremberg trials. It was followed by the “Subsequent Nuremberg trials” of other Nazi leaders before American military tribunals.

Shortly after returning from Europe, Ferencz was standing on a street corner in New York when he bumped into a former classmate from Harvard Law School, Murray Gartner.

Gartner was, at the time, working as a law clerk for Justice Robert Jackson of the US Supreme Court, and Jackson had just been assigned the task of serving as the Chief of Counsel for the United States at the International Military Tribunal at Nuremberg.

It was the chance encounter with Gartner that ultimately led Ferencz to Nuremberg, where he was placed under the supervision of Brigadier General Telford Taylor. Taylor was preparing for the “Subsequent Nuremberg trials”.

They took place in the same courtroom as the International Military Tribunal proceeding, in the Palace of Justice in Nuremberg, a city chosen in part because of its symbolism as the site of the Nazi party’s annual rallies and because of the Reichstag session that in 1935 passed the anti-Semitic and racist laws known as the Nuremberg Laws.

In the spring of 1947, in Berlin, where Ferencz had been sent as the chief of the Berlin Branch to delve through Nazi offices and archives, his team found a nearly complete set of secret reports describing the daily activities of the Einsatzgruppen.

The Einsatzgruppen were mobile SS death squads that operated in Nazi-occupied Eastern Europe. They mainly conducted mass killings, often shooting their victims into pits dug specifically for the purpose or ravines, ditches and quarries. Formed in 1939, it is estimated that between 1941 and 1945, they killed more than two million people, including around 1.3 million Jews and up to 250,000 Roma, as well as members of the resistance, homosexuals, members of the clergy and people with disabilities.

Upon discovering the secret reports, Ferencz flew to Nuremberg to request authorisation for a new trial. Taylor was adamant that his office lacked the resources for such a trial, but Ferencz persisted.

Taylor eventually yielded, naming Ferencz the chief prosecutor in the Einsatzgruppen Trial. It would be the ninth of the 12 “Subsequent Nuremberg trials”, and would see 24 commanders of Einsatzgruppen units face charges of war crimes and crimes against humanity. Two of those did not make it to the end of the trial – one because the case against him was discontinued for medical reasons and another because he committed suicide.

‘A plea of humanity to law’

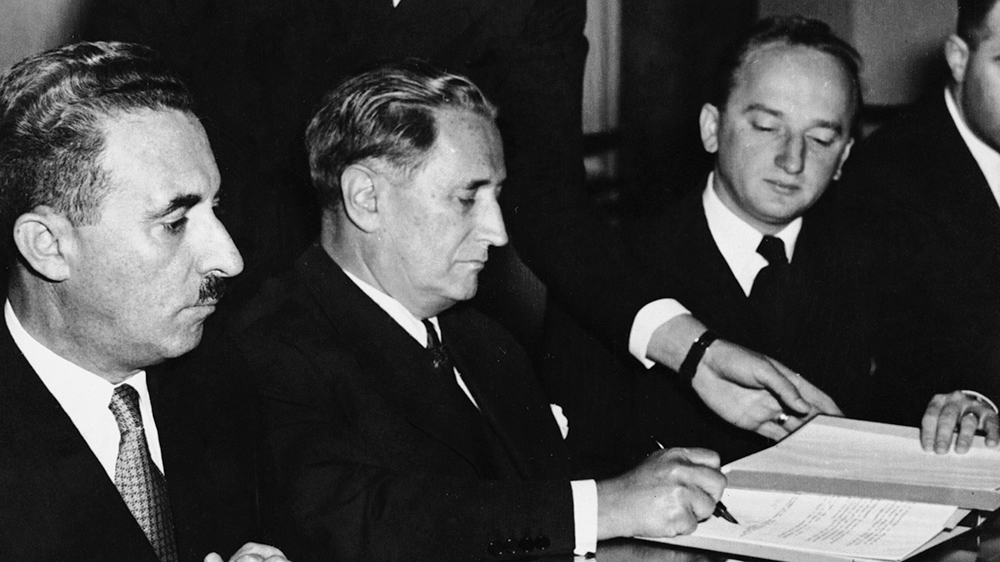

The stage was set for what the Associated Press at the time described as “the biggest murder trial in history”.

The men in the dock included the infamous lead defendant, SS Brigade Fuhrer Otto Ohlendorf, an economist with a PhD who was the commander of Einsatzgruppen D, which murdered nearly 100,000 people in southern Ukraine and the Caucasus during 1941-1942.

Ferencz was 27 years old and this was his first case.

He began the proceedings with one of the most powerful opening statements of the Nuremberg trials: “It is with sorrow and with hope that we here disclose the deliberate slaughter of more than a million innocent and defenceless men, women and children. Vengeance is not our goal, nor do we seek merely a just retribution. We ask this court to affirm by international penal action, man’s right to live in peace and dignity, regardless of his race or creed. The case we present is a plea of humanity to law. We shall establish beyond the realm of doubt facts which, before the dark decade of the Third Reich, would have seemed incredible.”

He introduced the prosecution’s evidence, argued its motions and then cross-examined some of the key defendants.

In April 1948, all 22 remaining defendants were found guilty.

After this success, Taylor promoted Ferencz to the position of executive counsel, managing the conclusion of the remaining Nuremberg trials.

In 1948, while still working out of his Nuremberg prosecution office, Ferencz took over the leadership of the Jewish Restitution Successor Organization, becoming the connective tissue between Holocaust prosecutions and reparations. He soon filed more than 163,000 restitution claims.

He then played a leading role in the successful negotiation of a Reparations Agreement between Israel and West Germany, an unprecedented nation-to-nation pact for atrocity compensation. He followed that by heading up the institution that assisted survivors in securing their share of the indemnity settlement, the United Restitution Organization.

By 1956, Ferencz was ready to return home with his wife and four children. He entered private practice in New York, in partnership with Telford Taylor, but continued with his efforts to guarantee reparations, filing a string of important cases for Holocaust survivors over the next two decades.

‘All roads lead to Nuremberg’

By the 1970s, Ferencz was no longer looking just to prosecute those accused of committing atrocities; he was also focusing on prevention.

His advocacy contributed to United Nations General Assembly Resolution 3314, which sought to define the crime of aggression.

He played a significant role in the 1998 adoption of the Rome Statute of the International Criminal Court, the treaty that established the ICC, whose statute eventually incorporated the definition of the crime of aggression he had helped to formulate.

In 2011, Ferencz delivered a portion of the closing statement in the ICC’s first trial – of the Congolese warlord Thomas Lubanga Dyilo.

He had come full circle – from an opening statement at Nuremberg to a closing statement at The Hague.

As Philippe Sands, UCL professor and counsel to the Gambia in its genocide case against Myanmar over its treatment of the Rohingya at the International Court of Justice, puts it: “[When it comes to international criminal justice], all roads lead to Nuremberg. It’s a straight line from Nuremberg to the Rohingya/Myanmar case in The Hague.”

Mark Drumbl is a professor of law at Washington and Lee University. He explains how “Nuremberg could have been a one-time event of victorious allies prosecuting the losing side.”

“Instead,” he explains, “Ferencz worked hard to create international institutions that would be permanent in nature. These institutions would not have existed without a vision of justice that started at Nuremberg.”

But, for Ferencz, it was a matter of particular disappointment that the US, despite playing a significant role at Nuremberg, did not ratify the ICC Statute.

It is a disappointment shared by his son, Don Ferencz, who told Al Jazeera: “By failing to join as a member of the ICC, the United States has turned its back on the lessons of Nuremberg. But ironically, neither France nor the United Kingdom have ratified the ICC’s amendments on the crime of aggression. Although rank and file soldiers in the US, France and the UK can be tried for violations of the laws of war, the politicians who send them out to fight and die in violation of the prohibition on the crime of aggressive war remain unaccountable to law.”

‘Law, not war’

Ferencz is known for saying “war makes murderers out of otherwise decent people.”

Speaking to Al Jazeera ahead of his birthday, he expanded on this idea, saying: “We must stop glorifying war. I have never heard of a war that does not kill the innocent.”

To Ruti Teitel, a professor at New York Law School, Ferencz’s enduring legacy is his work for the anti-war movement, particularly the movement against nuclear weapons.

“The best quote of Ben’s, which I think summarises his lasting legacy, is ‘I prefer law to war in all circumstances’,” Teitel explains.

Since retiring, Ferencz has devoted himself to advocating for peace, never tiring of repeating his trademark mantra: “Law, not war.”

Leila Sadat, a professor of law at Washington University School of Law, says: “Ben was writing about world peace when it wasn’t popular …. Since my first meeting with him, I have never, ever ceased to be amazed by his moral clarity, indefatigable energy and fighting spirit.”

While he has never sought accolades, he has received many. He has received the Erasmus Prize, been awarded the highest civilian honour by the German government and had his life’s work recognised by the government of Hungary.

But, Don points out, he has never been officially recognised by the US government. “Perhaps,” Don reflects, “the lack of recognition of those who stand for the rule of law reflects the political reality of our times.”

Bones in the grass

When visiting Auschwitz for the first time just after the war, Benjamin Ferencz picked up small bones in the grass.

He says he told himself: “I do not want to forget what I came to Germany for.”

“We think progress is built on institutions,” Drumbl reflects. “But sometimes a single individual, bucking trends, can make a huge impact.

“Ben’s qualities of individuality, tenacity and pluck are crucial as we look ahead to face the challenges of future generations.”

Ahead of his father’s 100th birthday, Don shared an anecdote about him.

“Most people don’t know that until about the age of 95 years old, my father stood on his head for about five minutes every single day.”

Apt, perhaps, for a man who has spent his life trying to correct a world turned upside down by war and man’s inhumanity to man.