What kind of art is the Pakistani state afraid of?

Artists say they are increasingly facing censorship as films, a book and art exhibitions stalled by security agents.

![Killing Fields of Karachi [Humayun Memon/Al Jazeera]](/wp-content/uploads/2020/03/82dd68c5c9584cb9a1dd3ae22e01bf9e_18.jpeg?resize=770%2C513&quality=80)

Karachi, Pakistan – In the last six months, three Pakistani artists have had their work either stolen or blocked from public access in an apparent tightening on public expression and art by the Pakistani state.

A public art installation depicting extrajudicial killings targeting the marginalised Pashtun community in Pakistan was destroyed and stolen from a public space in the port city of Karachi.

Keep reading

list of 3 itemsMedia watchdogs slam ‘brazen censorship’ by Pakistan

Pakistan’s new social media rules will ‘stifle dissent’

Newly translated copies of an award-winning novel, A Case of Exploding Mangoes, were seized and confiscated by security agents from bookstores across the country. And a celebrated film director received death threats for making a film that asked questions about societal moral policing – his film, postponed indefinitely.

What makes these artistic contributions so dangerous in the eyes of those who so violently censor them?

In late October, the Karachi Biennale, a public art festival in Pakistan’s largest city, came alive across the metropolis. One of its venues was Frere Hall, a colonial-era town hall in the heart of the city, and the site of an exhibit by renowned artist Adeela Suleman.

The installation titled, The Killing Fields of Karachi, consisted of 444 gravestones, each topped with an eerie, wilted metal flower.

It built commentary on the extrajudicial killings allegedly perpetrated by one of the city’s most notorious police officers, Rao Anwar. Anwar denies the charges, and his trial in a high-profile extrajudicial killing case is ongoing.

The exhibit, which drew from publicly available information and police enquiries, was violently erased in events that unfolded only a few hours after its opening.

First, a portion of her exhibit was padlocked and blocked from public access. As news of this spread, artists and activists from across the city began to gather around the remaining gravestones to hold a protest and question who had sealed the gallery.

Afaq Mirza, a civil administration official, soon arrived to break up the gathering. Speaking to the press, he ascribed the censorship to the Pakistani army’s Fifth Corps, a unit based in Karachi

Pakistan’s military did not offer comment on the incident when contacted by Al Jazeera.

![Killing Fields of Karachi [Adeela Suleman/Al Jazeera]](/wp-content/uploads/2020/03/636a466574f34a889ce2df8c3732da02_18.jpeg)

In the days that followed, the gravestones were reduced to rubble. Artists and students rebuilt the installation and staged a “lie-in” among the gravestones as a sign of protest. When they left, the gravestones were once again demolished. After they were rebuilt for a second time, they disappeared from the site.

For Suleman, the motive behind the censorship of her piece was clear.

“They have their own narrative, the State,” she says. Censorship of art in today’s Pakistan targets “anything which would try to change the general opinion of the masses.”

“For ISPR [Inter Services Public Relations Pakistan – the military’s press wing], I would say that culture is as important as the atomic bomb.”

According to the artist, ISPR creates content on television and through other media that is geared to garner support for causes prioritised by the State.

By directly challenging the power of a senior police officer who remains out on bail as his trial on charges of murdering innocent citizens is ongoing, Suleman’s installation evoked emotions that were not “state-sanctioned”.

“Anything that goes against religion or the army will be censored – both will be termed blasphemous,” she says drily.

Pakistan removed its last military ruler, General Pervez Musharraf, in 2008, replacing him with civilians elected through general elections. The 2018 elections, however, were marred by widespread allegations that the country’s powerful military – which has directly ruled Pakistan for roughly half of its 73-year history – engineered results.

“When we were growing up in Zia’s time we knew what we could say and couldn’t say, which was almost better,” she says, referring to the 11 years Pakistan was ruled by military ruler General Zia-ul-Haq from 1977. “Now, there’s this false facade of democracy.”

The state has gone ‘berserk’

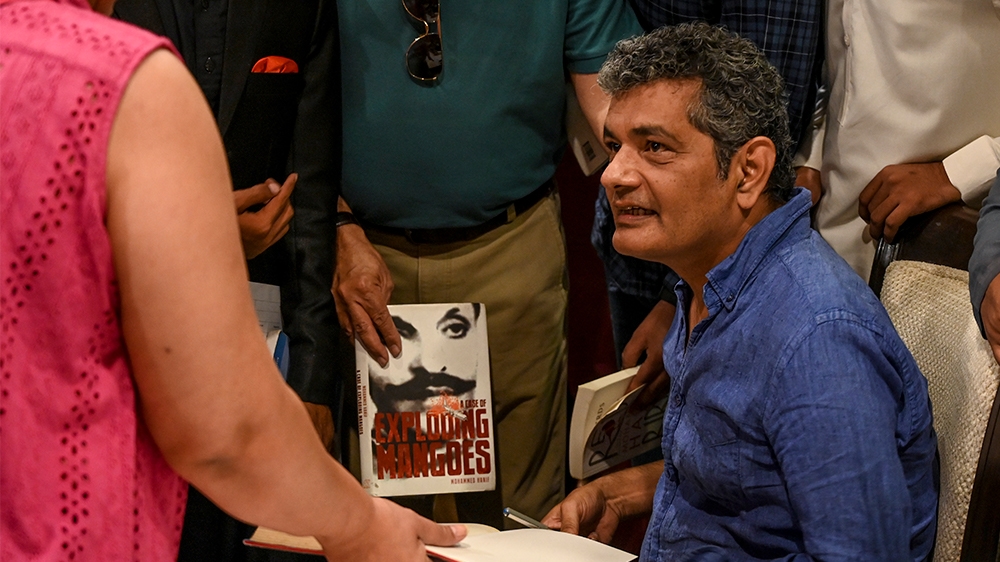

Zia-ul-Haq and his form of dictatorship are the subject of the book, A Case of Exploding Mangoes, a celebrated work of fiction by writer Mohammad Hanif.

![Killing Fields of Karachi [Humayun Memon/Al Jazeera]](/wp-content/uploads/2020/03/aafd2b21a0934b8a80574acb46435918_18.jpeg)

First published in 2008, the book is a satirical take on the life and death of Haq, depicting his final weeks in power before his death in a military plane crash in 1988, which is the subject of myriad conspiracy theories.

Hanif satirises the military dictator, celebrated by many for “Islamising” Pakistan, as a deeply paranoid man who wakes up every morning questioning who may be trying to kill him that day.

The book, first penned in English, won the Commonwealth Book Prize in 2009, was shortlisted for the Guardian First Book award in 2008, and longlisted for the prestigious Man Booker Prize the same year.

Eleven years after it was published, it was translated into Urdu and re-released in Pakistan in November last year.

Days later, Hanif says copies of the translated work were confiscated from his publisher’s offices by men in plainclothes claiming to belong to the country’s powerful Inter-Services Intelligence (ISI) agency.

Hanif, a seasoned journalist who has reported on multiple military dictatorships and was previously the head of the BBC’s Urdu language service in London, says the state has gone “berserk” when it comes to censoring art and literature.

“My book has been around for a decade,” he said. “My publisher has lived through two and a half military dictatorships, and this has never happened before. What we’re seeing is quite unprecedented in terms of censorship in Pakistan.”

“If you question any of their – even their past, then you’re not a good citizen. You’re being paid by some foreign power [according to them],” he asserts, as he describes the state’s definition of good citizenship, a category which, when thus defined, leaves no space for artistic voices like his and Suleman’s.

Film content

Three years ago, Pakistani filmmaker Sarmad Khoosat was awarded the government’s Pride of Performance award, conferred by the presidency to celebrate Pakistanis who have made outstanding contributions in the fields of literature, arts, sports, science or medicine. Today, he faces death threats.

Khoosat, a critically acclaimed film and television series director, has spent the last two years – and all his career earnings – making Zindagi Tamasha, a film that explores questions of class, religiosity, moral policing and gender constructs, by following the story of a pious man who is ostracised by his community after being seen dancing at a wedding celebration.

The film had been reviewed and approved on two separate occasions by the country’s Central Board of Film Censors (CBFC), as well as by two provincial censor boards.

However, a week before the film’s release in late January, a far-right religious group publicly objected to the film’s content, alleging it was blasphemous and denigrated religious people.

The Tehreek-e-Labbaik Pakistan (TLP) party has held widespread demonstrations in the past on the issue of alleged “blasphemy”, forcing the government to fire a federal minister in 2017 over a change to an electoral law they deemed to be sympathetic towards a sect the group considers apostates.

The film, twice approved by the CBFC will now be reviewed by the Senate Committee on Human Rights. If deemed objectionable by them, it will be sent to the Council of Islamic Ideology (CII), a constitutional body tasked with advising the government on Islamic issues, to be reviewed, in a historic first.

“This is not going to become common practice,” says Daniyal Gilani, who heads the CBFC.

And yet, despite this assurance, there is an undeniable pattern emerging of talented and celebrated Pakistani artists having their work barred and disappeared from public sites.

In an open letter to a former teacher published a month ago, Khoosat wrote:

“Sir, I hope you are reading this and are not too disappointed in me. I am rather happy that I am not sitting in some office where my ‘hands are tied’ and, despite being in a position to rectify things lawfully and dutifully, am staying quiet about blatant bullying and harassment of a citizen of Pakistan.

“Instead, I am freely (and responsibly) making some art that does matter. At least sometimes it does, or when it sees the daylight, it does.”

‘A sense of fear’

A common theme among the works of art that have faced censorship appears to be their questioning of official narratives, speaking truth to power, or problematising social and political structures.

That such works are considered unacceptable by Pakistan’s state, begs the question of what “acceptable art” is.

As Suleman mentioned, the media wing of the Pakistani military, ISPR, puts great stock in cultural production, meaning their productions are a good indication of state-endorsed “good art”.

When asked what kind of stories they’re interested in producing, and why they consider these stories to be meaningful cultural investments, ISPR declined to comment.

A cursory glance at some of their recent work, however, reveals a privileging of narratives that antagonise neighbouring India, weaving together ideas of hypermasculinity with hypernationalism.

A recent ISPR-produced television series, Ehd-e-Wafa (Promise of the Loyal), was, in fact, subject to a petition that sought to ban it.

Muhammad Zeeshan, the petitioner, declared that the TV series hurt his sentiments as it glorified the armed forces while negatively portraying other pillars of the state. While the petition was ultimately dismissed by the courts, it serves as one of the many instances of ISPR’s culture politics resulting in a public outcry.

In October, the then-chief of ISPR, Major-General Asif Ghafoor, took to Twitter to justify the inclusion of a misogynistic dance sequence in an ISPR-funded film.

“The item song is by an Indian girl in the movie as per her role, you may watch movie to know the context,” he said, seemingly implying that the woman’s citizenship was a measure of the respect she deserved.

So how does one understand the Pakistani state’s culture politics?

For Hanif, the current spate of censorship is an attempt to kill the art of resistance before its conception.

“The idea is to create a sense of fear, so that even when an artist sits to think about the kind of art they want to create, they’re scared of the state,” he says.

“Artists will begin to question, is this even worth trying? Will I be safe after I’ve created it?”