Argentina’s coronavirus patients, medical workers harassed

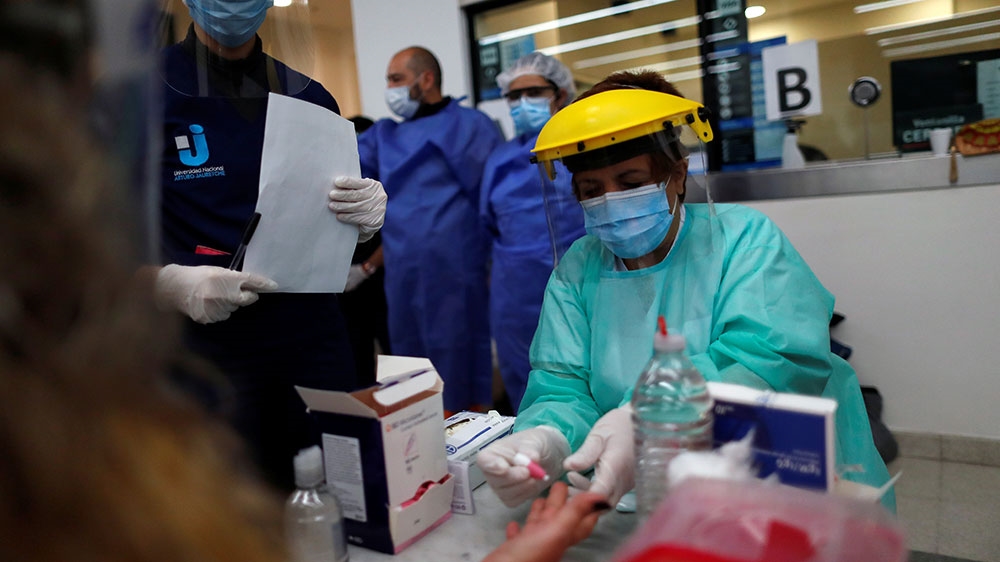

COVID-19 patients and those fighting the virus in Argentina are increasingly being stigmatised and threatened.

Buenos Aires, Argentina – The first thing Fernando Gaitan did when he saw the note posted inside the elevator of his building was cry. Days later, when he received another one on his door, he felt a stabbing pain.

“You’re going to infect us all,” said the initial anonymous letter directed at doctors, nurses, pharmacists and other healthcare workers on the front line of coronavirus pandemic. “Go away.”

Keep reading

list of 3 itemsArgentina’s lockdown: More people out of work and food

Argentina sees at least 6 femicides during coronavirus quarantine

The second note told Gaitan, a pharmacist in the Argentine capital, that if anyone in the building gets sick, “it will be the last thing you do in your life”.

“I cried, because we’re obviously living a very tense situation and I’m a human being like everyone else,” said Gaitan. “I honestly couldn’t believe it. Because I’m heading out to work and exposing myself.”

For weeks, Argentines have taken to their balconies every night to applaud and cheer on healthcare workers who are putting themselves in the line of fire to combat the novel coronavirus. But an uglier behaviour has also taken root, with several stories of harassment and threatening of medical professionals who are being accused of posing a risk to the community they are seeking to help.

It is not just doctors who are targeted, but COVID-19 patients, or those who are suspected of carrying the disease.

Marisol San Roman, who contracted the illness while studying in Madrid, has received a deluge of vitriol through social media channels. She has been called a leper, threatened with death, told her house will be lit on fire. She says she has heard worse stories from others who reach out to her in fear and indignation. Last week, someone torched the car of a doctor in the province of La Rioja who had tested positive for coronavirus. She had previously criticised the governor, who said that medical professionals need to be more careful in terms of taking precautions.

“When I started to see the level of violence I felt, this can’t happen. It’s not just a message of threats, it’s violence,” said San Roman, 25, who has been dubbed by the media “Patient 130” and has taken on a prominent role talking about the realities of the disease in Argentina. “If they are attacking people, nobody is going to get tested and people are going to live with symptoms and that’s the worst thing that could happen to our society.”

History repeats itself

The behaviour has been vehemently rejected by Argentine officials. The vice mayor of Buenos Aires called the attacks on healthcare workers “inadmissible”. The city’s ombudsman office expressed its “profound worry” and issued a warning to building administrations that the attacks are unacceptable. Argentina’s National Institute Against Discrimination, Xenophobia and Racism (INADI) also launched a campaign aimed at combatting the behaviour. “If the virus doesn’t discriminate, neither should we,” it said in its publicity campaign.

The INADI has seen calls to its office increase by 50 percent since a government-imposed quarantine started, from about 20 to 30 a day. Initially, the calls were from people of Asian descent who had suffered racial discrimination. But complaints also came from other vulnerable groups, such as transgender individuals, who faced eviction during the pandemic.

The threats against doctors started a few weeks ago, and most recently they have turned towards those with the virus. There have also been reports of mothers being barred from entering grocery stores with their children. Several cases have received media attention, but many more avoid the spotlight – they are often of people whose names, photos and addresses are published online and shared widely through social media. Often, anonymous notes are posted in residential buildings, as was the case for another doctor in Buenos Aires who was told to avoid common areas of her building.

“I would love to tell you that the behaviour is unexpected, but that’s not the case,” said Victoria Donda, director of the INADI.

“When we think of what is happening to people who have coronavirus, we just have to think back to people who, many years ago, had leprosy and were ostracised by communities even though you couldn’t transmit leprosy through touching. Or more recently, the people who had HIV, or the people who worked with them,” she told Al Jazeera. “When you think about it, that society … is the same one that is responding in this way.”

Misinformation

Argentina has been under a mandatory lockdown since March 20, meaning that most people must stay in their homes. But even before that, the government had placed importance on monitoring suspected cases of COVID-19, and ensuring that people who had returned from parts of the world with high rates of infection adhered to a mandatory isolation period. It urged citizens to report anyone who violated the rules and the calls flooded in.

In the northern province of Jujuy, the governor was forced to apologise after he suggested officials should mark the doors of anyone who had recently returned to the province, to ensure they were completing their quarantine as they awaited test results on whether they had the virus.

“Stigmatisation always generates hate and violence, which is very far from my intention,” Governor Gerardo Morales said following outrage over his comments.

Donda says the discriminatory attacks are fuelled by fear and disinformation. “And there is also hate and violent conduct, everything is mixed together,” she said.

Tomas Duarte’s own experience started on March 22, when he called the local health authority of his city of Rosario, the largest city of the province of Santa Fe, to advise he had a fever. They sent a team to take his temperature on the doorstep of his house. The neighbours noticed. And soon photos of the 26-year-old and allegations that he had tested positive multiplied to the thousands on Facebook and WhatsApp. In the middle of all this, he received a prank phone call telling him, falsely, that he had contracted the virus. It took days before the official results were revealed: He did not have COVID-19.

“The insults, the threats, the warnings – things that I had not yet done or said, they were already accusing me and insulting me. It was horrible,” he told Al Jazeera. “The paranoia and staying inside makes us police our neighbours,” he added. “I mean, we’re all scared. That’s the reality. But doing something like this, it doesn’t get you anywhere.”

San Roman, Duarte and Gaitan have each filed criminal complaints that are being investigated. And they all say the support from the public far outweighs the hate.

“The messages that I’ve received from people are filled with so much love,” said San Roman, who has recently tested negative for the virus for the first time.

“It fills your soul,” said Gaitan. Nonetheless, he has installed a camera outside his door, and scans his home every time he walks in to make sure no one is lurking.

Donda says the complaints are still coming in to the INADI. But she has been encouraged by the counter acts of kindness that have sprung up in the wake of the organisation’s publicity campaign. Neighbours are now installing signs of endorsement and love in their buildings.

“This is an opportunity. An opportunity to become a society with more solidarity,” she said. “We’re the ones who build the future. We can choose to make it better, or we can choose to make it worse. And we can’t get out of this one alone.”