What a month on Mexico’s coronavirus front line feels like

We filmed in the ambulances, the hospitals and the hotspots, grappling with confusing messaging, grief and exhaustion.

I was staring at the screen, struggling to hit the send button. It was one of those emails – you feel like you are about to jump off a cliff edge and you’re not sure how deep the water below is.

I had been writing it in my Mexico City apartment. That was also where I had done virtually all my reporting on COVID-19 up until then. It was a simple process. “Stringers” from news agencies sent in video from all over Latin America. I wrote scripts to go with it and we filed the reports. I had hardly been outside since the pandemic began and I liked it. It was a welcome change from a routine of constant travelling.

Keep reading

list of 4 itemsMexico’s teachers seek relief from pandemic-era spike in school robberies

‘A bad chapter’: Tracing the origins of Ecuador’s rise in gang violence

Why is the US economy so resilient?

But in Mexico, the cases were starting to rack up. That weekend I had decided that I needed to change my approach.

I had to get out – to hospitals, ambulances, markets; see for myself what the coronavirus was doing to the capital.

The email that I was struggling to send was to my bosses. It was my plan: our team would rent an apartment for a month. It would become a temporary COVID-19 bureau – a base from which to report – stuffed with gel, masks, bleach and hazmat suits.

It would also be a home to those on the team like myself, who would need to move out of their own apartments and isolate from their families during this “special” coverage. The coverage would last for a month. That already felt like a long time.

I hesitated again over the email, then finally whipped up the courage to press send. A week later, after a lot of pacing the floor and nail biting, I got a decision from the bosses: greenlight.

I said goodbye to my wife (who was already regretting that I hadn’t made a will) and moved into my new temporary home.

The team was ready. Producers Amparo Rodriguez, Pablo Perez and Andalusia Knoll. Camera people Vanessa Gomez and Gustavo Huerta. Video editor Leslie Atkins.

But our first day filming was a disaster. Something had got lost in translation. We thought we were heading out with an ambulance team. They thought we were filming them simulate a rescue at their HQ. Nobody could change the other side’s mind. After polite expressions of regret from all concerned, we left.

It was an inauspicious start. What if this was all for nothing, I wondered. What if every door was to be shut? I was nervous.

Then Pablo worked his magic. Twenty-four hours later we were flying down a Mexico City highway with paramedics Mydori Carmoni and Sergio Villafan, as they delivered Jose Luis Montano – a COVID patient – to hospital encased in a transparent cylinder.

Their patch was Nezahualcoyotl, a boisterous, young Mexico City district often referred to as “Neza”. Before they had picked up Jose Luis, persuading his family to let him go, they had been treating drunks, the elderly and coronavirus patients with the same professional compassion.

During a rare moment between call-outs, Sergio opened up. He had just lost his own grandad to COVID-19, he explained, showing me pictures of him. At first, he had wanted to take a break from this job, he said. But he soon changed his mind, deciding to use his own sense of loss to help save others. It was one of those special moments this job sometimes gives you – a window into a stranger’s soul.

Those moments happened again and again as our coverage continued. I particularly remember Tomas Guillen and Christian Colmenares, two young men who waited every day outside of Mexico City’s General Hospital. They clutched letters which they sent in with the nurses to read to their respective fathers, both of whom were hooked up to ventilators.

I don’t think any of us were dry-eyed after Tomas and Cristian read us the words they had written to their fathers that day.

We later found out that both of their dads had died. Our producer Amparo was the force behind that story and it was especially hard for her.

I was worried about Jose Luis, Mydori and Sergio’s patient, too. His sister Mariela and I had kept in touch – sending each other audio messages most days. He was still in hospital and wasn’t getting any better. Weeks passed. He seesawed between recovery and relapse. Our documentary, Frontline Mexico: The Fight Against COVID-19, tells more of his story.

Meanwhile, the rest of our coverage began to take shape. We went to hospitals and to the country’s largest fruit and veg market – a COVID hotspot. We talked to doctors, nurses, patients and their families.

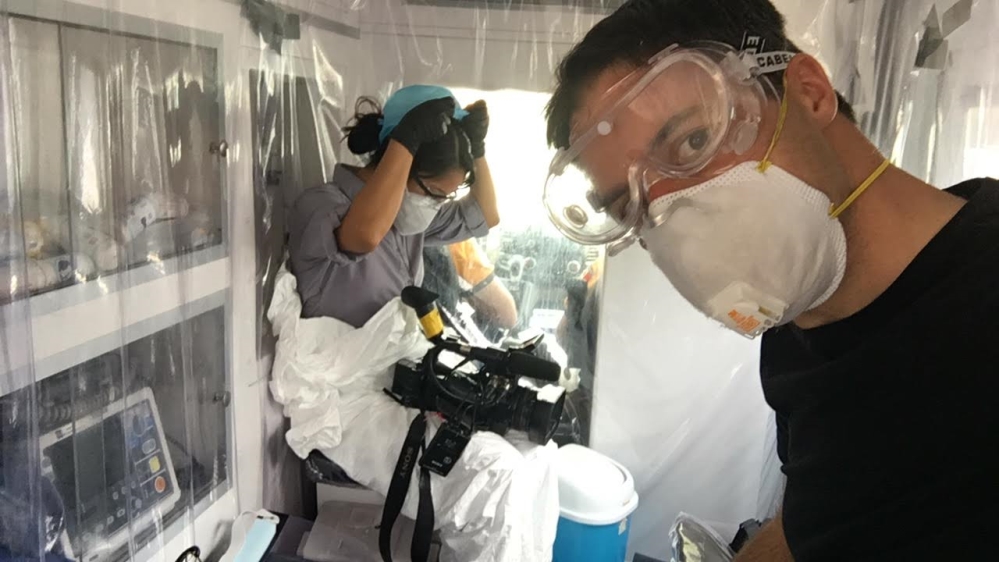

The days were long. And the coronavirus always added an extra layer: Sweat-inducing hazmat suits, protective glasses through which the world was just a hazy blur. Vanessa, our camerawoman, had to spend a lot of time fumbling in plastic gloves to adjust the zoom or focus.

The day wasn’t over when we wrapped. There were still rituals to perform: spraying each other with alcohol before getting into the car, then again at the COVID bureau front door. Disinfecting the gear. Stripping, showering, washing clothes. I guess it added two hours to every day.

Vanessa was our team’s chief COVID protocol enforcer. In return I made her English tea in our temporary bureau and we both ate copious amounts of “Conejos” (tiny chocolate rabbits).

I’m not sure why the latter became so popular with us – but as Sinatra said, whatever gets you through the night.

Except that in the end, it wasn’t getting me through the night. I wasn’t sleeping, and even when I did, I dreamt of what, and who we had filmed that day.

It was partly the workload, partly the risk. But mostly the stress of trying to get a story right while attempting to process a barrage of new information.

It didn’t help that the Mexican authorities’ own messaging was complicated. The president was out hugging and kissing his supporters even while his government called for social distancing. And the country’s coronavirus czar – a charming epidemiologist called Hugo Lopez Gatell, insisted to me that he had no regrets over his unorthodox strategy: (low testing, soft quarantine) even as the number of cases continued to rise.

Perhaps he was right. Mexican infections rose slower than in Spain and Italy. That probably stopped hospitals becoming overwhelmed.

Perhaps he was wrong. Mexico’s death toll has grown to be the fourth-highest in the world.

Nothing was, or is, wholly clear. And we faced the conundrum for reporters everywhere: this insidious virus is everything and nothing at the same time. To the vast majority of people, it is little more than a flu. To more than 600,000 worldwide it has been a ruthless assassin.

That means that every report, every word begins to feel either an exaggeration, or an underestimation.

I wrestled with that constantly during the coverage and in the three weeks that followed, while Leslie, our talented video editor, and I put together this documentary.

Did we get it right in the end? I leave you to judge – if you care to watch the documentary at the top of this page.