Black Lives Matter protesters in New York: ‘Confrontation works’

Protesters share their experiences of systemic racism and stories of solidarity on the streets.

![Black Lives Matter NY - Tucker feature [don''t use]](/wp-content/uploads/2020/07/8f5f0be32fca48bf9e53754a4cb27a31_18.jpeg?resize=770%2C513&quality=80)

When the first Black Lives Matter protests reached New York City in 2014, Carlos Williams stood on the periphery – at the literal edge of the action, in fact.

“The closest I ever got was putting my toes on the edge of the sidewalk and facing off with a cop … chanting ‘Black Lives Matter’. I didn’t want to get into the fray,” the 33-year-old who calls himself a “Black kid from Brooklyn” explains from his office in Manhattan’s financial district.

Keep reading

list of 4 itemsFormer US police officer sentenced in killing of Black man Elijah McClain

US paramedics found guilty in 2019 death of Black man Elijah McClain

Angela Davis: ‘Palestine is a moral litmus test for the world’

Williams had just started a brand strategy company in 2013, and worried that public association with the protest movement could harm his “image” and his work. “We had some corporate clients; I didn’t know how they’d react if I got arrested and it made the newspaper,” he recalls.

But in the years since, that has changed.

“In the last couple of years, I just don’t care,” he says. “Why would I want your money if you don’t believe I have the right to exist … Why am I courting people who wouldn’t work with me anyway?”

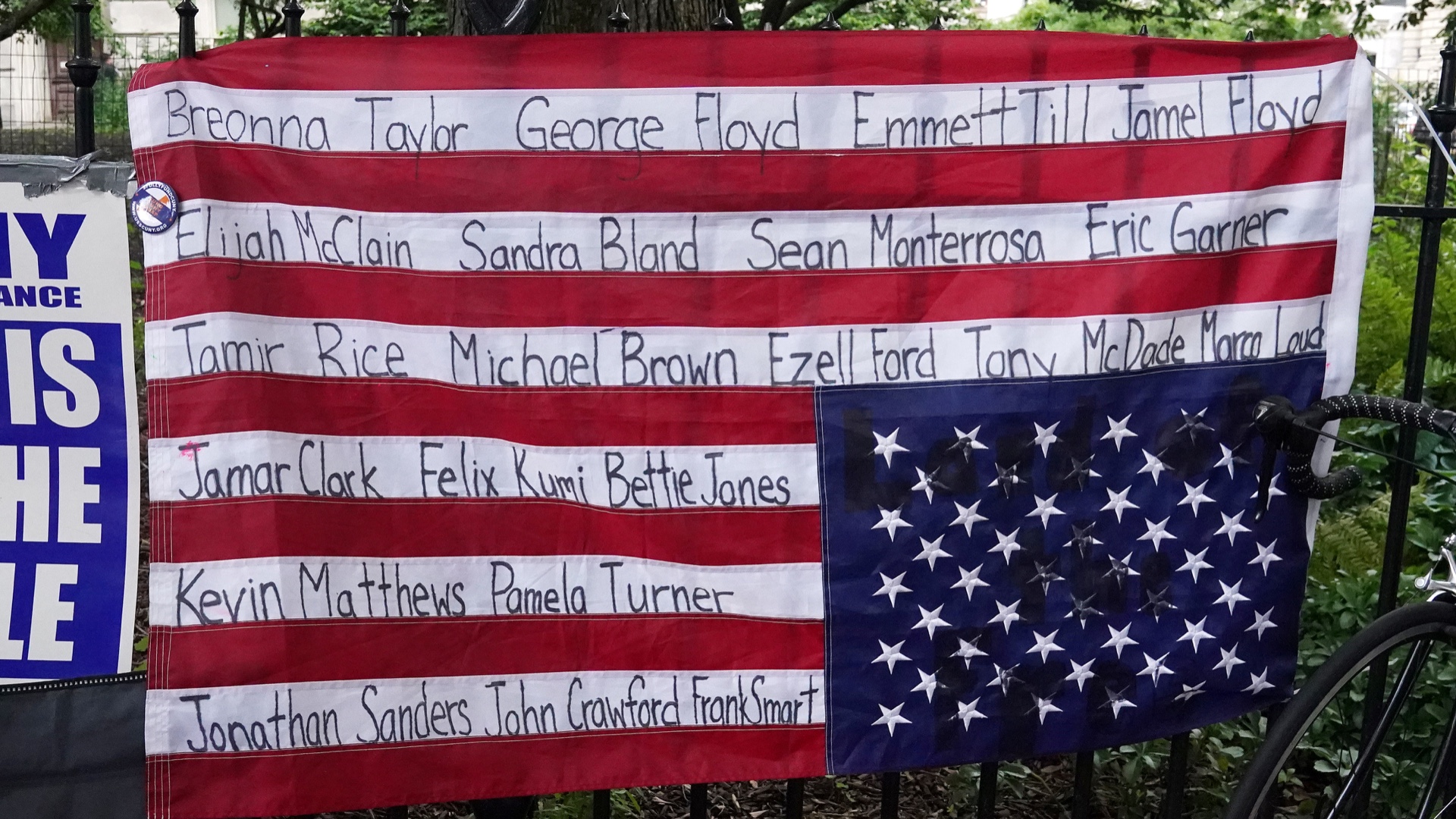

Williams and I walk north, meeting a thousand-person march as it is leaving Washington Square Park. It is just one of the thousands of Black Lives Matter demonstrations happening across the United States in the aftermath of George Floyd’s killing at the hands of Minnesota police in May. We stay on the edge of the crowd as it winds through the city, past Union Square and Madison Square, past businesses shuttered because of COVID-19 or looted during the protests.

![Black Lives Matter NY - Tucker feature [don't use]](/wp-content/uploads/2020/07/b8f2a49c238749b68997bfaeaeebc676_18.jpeg)

The first weekend of protests saw at least 47 police cars torched. Every night during the next week, police beat protesters who stayed out beyond the 8pm curfew. But this protest, like practically every other one in the city since curfew ended, is peaceful.

The crowd eventually heads towards Columbus Circle and Central Park, at which point I walk with Williams back to his downtown home. On the way, we pass two more sizable demonstrations – different people, different protest signs, but all with similar messages addressing decades of police killings and centuries of racial injustice towards Black Americans.

Police in the US have killed about 1,000 people a year between 2015 and 2019, with Black Americans being more than twice as likely as white Americans to be killed, according to the Washington Post’s public database. For contrast, UK police killed 23 people from 2006 to 2016, according to the Independent.

In New York City, the police department (NYPD) typically patrols Black neighbourhoods. Stop and Frisk, known nationally as a Terry Stop, exists in a legal grey area – not quite an arrest, but involuntary detention nonetheless. Started in the 1990s under Mayor Rudy Giuliani, there were more than five million Stop-and-Frisks from 2002 to 2013 under Mayor Michael Bloomberg, whose policing was found by a federal judge to have violated two constitutional amendments regarding illegal search and seizure, and the civil rights of Black Americans and other minorities.

According to the New York Civil Liberties Union, which successfully sued the NYPD for its Stop and Frisk records, young Black and Latino males only made up 4.7 percent of the city’s population but accounted for over 40 percent of Stop-and-Frisks. Despite finding weapons on white people at a higher rate, Bloomberg said in a 2013 radio interview: “I think we disproportionately stop whites too much and minorities too little.”

Encounters with police

Williams learned early on about the racial dynamics that determine life in America. He remembers being five or six when the Rodney King riots were on TV in the background in his parents’ living room. He also knew at a very young age that he never wanted to end up like Abner Louima, who was viciously sexually assaulted by police in 1997, or Amadou Diallo, who was shot 19 times by police in 1999.

Like most Black protesters, Williams has had many close encounters with the police. The “craziest” one, he says, happened five years ago when he was on his way back from playing baseball with a team he is a part of in Long Island.

He had got off the shuttle back home in Brooklyn at around 1 or 2am, he says. He was two blocks from home but desperately needed the toilet, so decided to run the rest of the way. He was half-a-block from home when he heard a van door slide open in the darkness beside him.

“I look to the left and there’s a dark unmarked van,” he recounts. “I hear people hopping out. I’m like, oh s*** I’m getting robbed.”

It's not about what you're wearing. It's not about what you're doing and who you are. It's about the colour of your skin

But it turned out to be two police officers, a man and a woman, who started rapid-fire questioning him about why he was in the area, why he had been running, and where his ID was.

“I had lost my ID, but was carrying my passport,” which they retrieved from his trouser pocket while his hands were in the air. He is grateful to have had something to show them. “A lot of Black people and poor people in general don’t have passports. So if you lose your ID, your life is going to be infinitely worse. If I didn’t have my passport this would’ve gone way different.”

After a second round of questions the officers finally let him go.

“Want to know the kicker?” he asks. “I had changed into light blue pants, a button down shirt, and plaid polo sneakers. The most preppy thing I could’ve been wearing … looking like a Beach Boy.”

“So it’s not about what you’re wearing. It’s not about what you’re doing and who you are. It’s about the colour of your skin.”

In 2014, after the killing of 18-year-old Michael Brown and the later acquittal of the officer who shot him, the Black Lives Matter movement ignited in Ferguson, Missouri, soon drawing global attention to the extent of police violence against Black people in the US. The protests themselves spread nationally. In New York, throughout 2014-2015, any time a police killing trended on social media, a few hundred protesters gathered in Union Square marching north to Washington Square Park, blocking the Holland Tunnel to New Jersey, or entering Times Square, where their protest slogans would inevitably be drowned out by the bright lights and energy of the tourist mecca.

The protests inspired The Guardian, and later the Washington Post, to keep track of US police killings, which had never been tracked at any level by the US government. Still, for the next six years, politicians did little to address the thousands of annual police killings, or mass incarceration of Black people in the US.

Then, on May 28, after a multi-day stand-off with the police over the killing of George Floyd, the residents of Minneapolis torched the local police station. Emboldened by such an act, the residents of nearly every city in the US have taken to the streets, undeterred even by the pandemic sweeping through the country.

‘The meat in the math’

Raul Serrano, a software engineer who lives in New Jersey, first joined the Black Lives Matter movement in 2014 after Eric Garner was killed. He says he took to the streets of New York again last month after he “started seeing people get taken with our own eyes and on TV”.

“The goal became to try to prevent people from being taken. That was either by de-escalating situations or fighting and trying to break people free,” he says, something he refers to as being “the meat in the math”.

“Officers have to do calculations every second they’re out there. They’re looking at us, wondering if they can take us every second. As long as there’s a lot of meat on this side, they are gonna have to do math on that and it’ll force things to de-escalate and calm down,” he explains.

![Black Lives Matter NY - Tucker feature [don't use]](/wp-content/uploads/2020/07/2e406f2170be4f3c805a306431fe2b01_6.jpeg)

But that is not always what happens. On June 2, he was assaulted during a protest near the heavily militarised Union Square, he says. Serrano, his wife, and a couple of friends had met up with a large crowd in downtown Manhattan; a few hundred of them stayed out protesting beyond the 8pm curfew. The crowd was followed closely by police, who Serrano says attacked unexpectedly at a point when the march thinned out.

“I got beat by six different officers,” says Serrano, who previously received combat training at the US Military Academy West Point. “They went for the knees so hard. They didn’t strike me in the head or groin, which was nice,” he adds.

I always just understood the police as people who would've been criminals if they hadn't been cops.

Police became even more violent after the crowd had been beaten into submission and began to flee, he says. “I’ve known violent people my whole life. If they see somebody express weakness, they want to hurt them more,” Serrano explains. “The entire unit came sprinting down the street and chased us for two blocks, slamming people against cars, tackling people off bikes, beating people down to the ground, five officers to one civilian.”

After a week of mass police violence, only three NYPD officers had been internally disciplined, and none were criminally charged.

Serrano’s family is Puerto Rican and Filipino. Although he joined the military for a while after 9/11, he says he grew up always being wary of the police.

“I was raised around police officers. In my family half the people are soldiers, firefighters, and cops, and half are in prison or have records. And the Venn diagram overlaps. I think I always just understood the police as people who would’ve been criminals if they hadn’t been cops,” he says.

![Black Lives Matter NY - Tucker feature [don't use]](/wp-content/uploads/2020/07/a8ddb81c52494e8490981c20fd395f49_18.jpeg)

The June 2 incident was not his first run-in with the NYPD. As a teenager in Queens, he was stopped and frisked “at least once a month” on his commute to and from Stuyvesant High School, NYC’s premier public school, he says, relaying a conversation he had with a white acquaintance who works in his building.

“He was like ‘Stop and Frisk? Did you ever get stopped and frisked?’ I was like, ‘yeah, like once a month.’ He was like, ‘holy s***, I never got stopped and frisked.’ I was like well, I don’t know what to say. I think the reason is pretty obvious.”

Like Williams, Serrano learned about the harsh realities of life in America at a young age.

“I remember having an argument with my mom when I was 6 [in 1993]…It was about Martin Luther King’s assassination. For some reason I was convinced it happened hundreds of years ago because we didn’t live in a world where I believed overt, systemic racism and the assassination of political leaders was a thing,” he says. When he discovered how wrong he had been, his reaction was: “Tell me how that’s possible!”

‘Judged before they’re known’

In recent years, the experiences of Black Americans have come to light in large part because of Black Lives Matter, and how it has mobilised its message across the world.

“I think a lot of white people, and people in general, didn’t really believe that these things were actually happening. They had glimpses in the past; but now everything is recorded,” says artist Sylvia Hernandez from her Brooklyn home and quilting studio, where she has been holed up for months in the midst of the global COVID-19 pandemic.

![Black Lives Matter NY - Tucker feature [don't use]](/wp-content/uploads/2020/07/2ebb21db55ea40d190943fe9ca19c092_6.jpeg)

During a phone interview in mid-June, Hernandez tells me about growing up in New York in the 1960s. Hernandez has Black, white and Indigenous Caribbean heritage, but identifies and is perceived as being Black according to the US’s centuries-old race dichotomy.

She has never had an encounter with the police, but says she was “always scared” for her sons growing up as teenagers in Brooklyn in the late 1990s. “Right by the train station was a regular place for the police to stop and frisk the kids. It was a regular thing for them… I was like, ‘what is the point of all this?'” she says.

“When we were kids, the police would round up kids on a regular basis. There were a lot of gangs. The police would just round up whoever was around and it would be like, ‘huh, what just happened? Why did everybody just disappear?'”

I think everyone is just finally standing up for themselves and others, pulling away from the me mentality, where it's all about me.

In recent years, Hernandez’s work as an artist and teacher has increasingly taken on themes of police brutality, mass detentions, sexual violence, immigrant detention, and naturally Black Lives Matter, like her 2016 piece Target of Injustice, made in collaboration with AgitArte and El Puente.

“I make social justice quilts that tell some kind of story,” she says.

“If you tell young people, ‘go read about this,’ they look at you like you’re crazy, like, ‘I’m not going to read about it’. But show them this quilt, they may want to look into it. We sit and talk about it. It opens the door of communication,” she says.

“There’s a lot of kids that come from rough backgrounds, and just the simplicity of telling them, ‘it’s going to be okay, we’re going to get through this’. Being someone they need, being an ear for them. I tell them, ‘if you just want to sit and talk, I will sit and listen for as long as you want.’ … Sometimes they don’t have anybody who will listen. They know the situation of being stopped for no apparent reason. They understand all of this, being judged before they’re known.”

![Black Lives Matter NY - Tucker feature [don't use]](/wp-content/uploads/2020/07/cee1911de3574d3eb12570e8a02d8c22_6.jpeg)

Hernandez will be travelling to Minneapolis this summer to present quilts related to the Black Lives Matter movement. Talking about anti-Black racism, she says she worries about the ideas some Black children seem to have internalised about their own skin colour.

“I did summer camp a couple years ago and it was mostly Black and brown kids. They were doing self-portraits,” she says. “This little Black girl comes in, a little chubby with braids in her hair. She was just a beautiful little girl. She said, ‘I made a painting in school! I looked in the mirror and painted what I saw!’ I said, ‘great!’ She showed me. She’d drawn a blonde, white princess.”

“I said, ‘oh, that’s beautiful,’ but on the inside I was crying … She made herself a blonde, white princess. All I could think of is who told this beautiful brown girl that what she is is not enough?”

Been a long time coming

The current protest moment has also seen new solidarity across racial lines – especially on the protest front.

When asked if she was surprised by the new white solidarity, Hernandez points to the white people also being shot by American police every year. “White people are being treated, unfortunately, the way that Black and brown people have been treated. It’s across the board now. Everybody’s getting it,” she says.

“I think everyone is just finally standing up for themselves and others, pulling away from the me mentality, where it’s all about me,” Hernandez feels. “It’s more about let’s work with the community and do stuff for each other.”

![Black Lives Matter NY - Tucker feature [don't use]](/wp-content/uploads/2020/07/b702a1a7c2664e7895e1912f728f0020_18.jpeg)

Serrano is rejuvenated by the new sense of solidarity out on the streets. “When people scream things like ‘White allies to the front!’ and people are just sprinting to the front [of a protest], that’s incredible. When people are screaming ‘Chain up!’ ‘Hold the line!’ and people do it, that’s incredible,” he says.

“When people know they might get beaten, you can see them visibly shaking, you know they’ll be crying for the next two days, and they still want to come out and do this, it’s just incredible. I don’t think I ever would’ve expected it.”

On questions about the protesters also becoming violent, he asks: “Does destroying a cop car hurt a person? If it doesn’t, then is putting cuffs on a peaceful protester more violent?”

This is the only way any population of people has ever figured out how to fight a much more technologically advanced occupying force.

“I speak to a lot of people who are much more right-leaning in my everyday life,” he says. “They often seem to conveniently forget the fact that they’d die to defend themselves. They don’t find it easy to abstract that theory out into the real world. This is the only way any population of people has ever figured out how to fight a much more technologically advanced occupying force.”

Sergio Tupac Uzurin, a photographer originally from Queens, has been an organiser for many years, protesting with Black Lives Matter in 2014 and working with Critical Mass and Free Them All Fridays. When the demonstrations kicked off in Minneapolis after Floyd’s death, he says he stayed up for two nights watching it all unfold.

“I was enthralled. I was ecstatic, excited, a little nervous for them. Frankly it’s been a long time coming.”

![Black Lives Matter NY - Tucker feature [don't use]](/wp-content/uploads/2020/07/4b7a1ef9b5a640db93a71156daac0f08_18.jpeg)

Talking about one protest he attended in Soho, he recalls the sense of “camaraderie” among people.

“What really struck me is I overheard them shouting, ‘no local businesses!’ They were pointing out businesses, ‘there’s Coach, there’s Balenciaga’. But then they would pass by a bodega and say, ‘no corner stores’. And I’ll never forget this, because the Asian guy who I assume was the owner was standing out front. And they said ‘we love our corner stores’.”

He feels it is “hypocritical” for people to call out protesters more than they do the police who are arresting and beating people. About the demonstrations, he says: “I don’t want to say violent or nonviolent. I want to say effective and not effective.”

The way forward

Confrontation is necessary, Uzurin reminds me nearly every time we meet, multiple times a week now, whether on our bikes at Brooklyn’s McCarren Park, or at the ongoing City Hall encampment that he played a crucial role in organising.

“Confrontation works,” he points out during a phone interview in mid-June, explaining: “In the past 10 days, we’ve passed Breonna’s law in Louisville. The NFL has expressed remorse for treating Colin Kaepernick like s***. The four police officers that killed George Floyd have been arrested. There was a nine-figure budget cut being proposed for the LAPD. The Confederate statues are being removed from the South. And that is in 10 days, half of those days involving rioting nationwide.”

Williams holds a similar view. “In school you’re taught nonviolence. And I think that’s on purpose,” he says. “It’s ingrained in you, ‘be a peaceful Black person because that’s how you effect change’. No one says, hey they rioted after Martin Luther King was killed and that’s how the Civil Rights Act of 1968 got passed.”

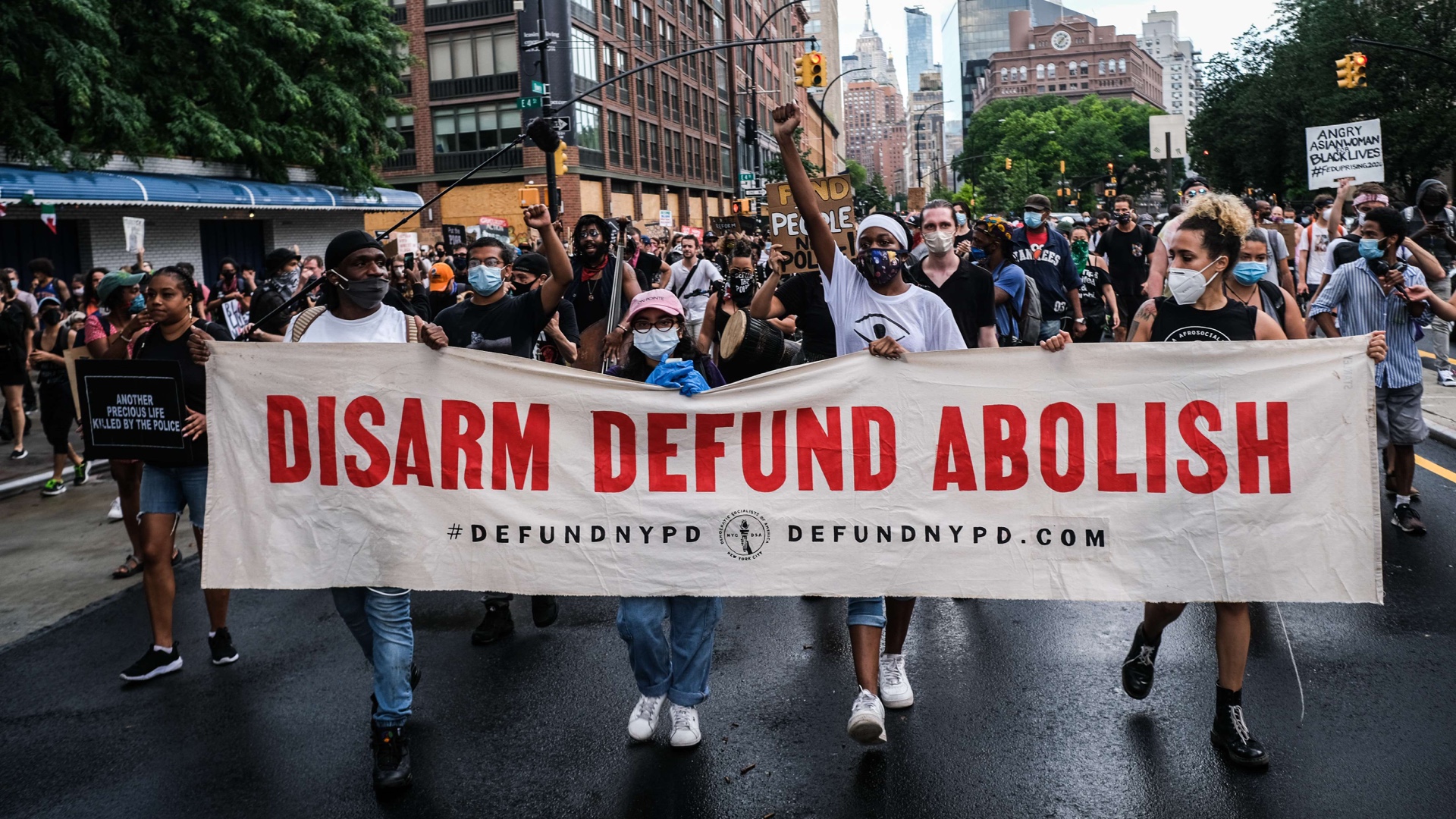

The call from most protesters in the streets is to defund the police and change their mission. Demands typically centre around reducing police roles as first responders to mental health crises, noise complaints, traffic violations, and drug abuse, removing police from schools and stripping police of all military-grade weaponry that they received during the so-called “war on terror”.

Williams is interested in the idea of splitting off a portion of the police department, including its budget and tools, towards “officers who want to change the mission” to something more akin to education and understanding.

Still, others demand the complete abolition of the police and the US carceral system. “The goal is abolishing the police. The compromise is defunding the police… We have to imagine a world without police, period,” Uzurin says.

“I think it is the only way,” Williams says. “Honestly I don’t think we have a path forward. We can’t fire the police force and the next day expect to have new police.”

He hopes for the best, but also worries about next year when things have died down. “I hope 2021’s challenge is not the backlash, like [people thinking] ‘I’m gonna smack a Black person’. That can’t be the 2021 thing,” he says.

At the same time, he emphasises equal access to knowledge and opportunities as a way to help change things in America.

“Education. This is my challenge to racists,” Williams says. “If you want to say Black people are lazy, no good, stupid people, give them equal opportunity. Give them the same schools that you have, and the same opportunities that you have. And then if Black people fail with those same opportunities, like really creating equal opportunity, then you get to be right.”

“But you can’t hold a foot down on them and say, see they can’t get up.”