Postpartum depression survivors on pandemic parenting

For survivors of postpartum depression, some aspects of parenting through the coronavirus feel all too familiar.

I had known the school cancellations were coming. But the news still pummelled me, sending waves of despair through my body. The cancellations felt like a cage descending from above.

Being confined with my family during a global pandemic is not something I have experienced before. So why does it feel so familiar?

Keep reading

list of 4 itemsMexico’s teachers seek relief from pandemic-era spike in school robberies

‘A bad chapter’: Tracing the origins of Ecuador’s rise in gang violence

Why is the US economy so resilient?

In my late 20s and early 30s, I craved motherhood. I would place my palms to my flat belly, imagining it ripening into a firm ball of baby. I daydreamed of motherhood: I would brim with love and patience as I stretched into a new version of myself.

But parenthood is almost never what we imagine it will be. Like any love, it is full of texture and nuance, complexities we could never articulate until they have arrived on our doorstep, fully packaged.

Just days after my long, slow and traumatic labour with my son, a heavy hopelessness enveloped me. I would swaddle, nurse him and set him in his bedside bassinet. I would listen, vigilant for his soft snorts, as my skin hummed with anxiety and my mind buzzed and barked: “You’ve made a terrible mistake. You’re not cut out for being a mum. You’re trapped.”

With my history of anxiety and depression, I had known I was at risk for a postpartum mood disorder. But just like I could never have conjured my son, with his stunning slate blue eyes and restlessness, I could not have imagined how bleak it would feel, how dangerous. I did not know that thoughts of hurting my beautiful son could blaze through my mind, uninvited. Or that instead of feeling motherly, I would feel like a caged ocelot, pacing and jittery, incapable of adapting to my sudden and startling lack of freedom.

Pandemic parenting

“Does pandemic parenting remind you of postpartum depression?”

I tapped out the text to a few friends who, like me, had struggled with postpartum depression and anxiety.

Like then, the days slide into one another, a blur of questionable hygiene. Forced back into the intensive parenting we thought we had graduated from, we attempt to juggle work, parenting and self-care. If our partners are the breadwinners, as mine is, we are again suddenly responsible for the vast majority of childcare, which can jostle our sense of identity in a way we have not experienced since first becoming mothers. The learning curve is, just like with new motherhood, painfully steep, as we step into new roles as teacher, tech support, therapist and fetcher of all the snacks.

The answer from my friends, over and over again, was a resounding, “Hell, yes”.

Karen Kleiman, a licensed clinical social worker, says that since the pandemic began, many of her clients have been reminded of their battles with postpartum depression. Other past traumas have also resurfaced.

“The social isolation and lack of distractions and stimulation is causing women to sit with their thoughts in a dark spot that is reminiscent of intense suffering,” Kleiman explains.

When we spoke, Kleiman had recently talked with a client who was having flashbacks related to sexual abuse that had happened 25 years earlier. “I said, ‘Why do you think this is happening now?’ and she said, ‘Because I’m terrified and I’m vulnerable.'”

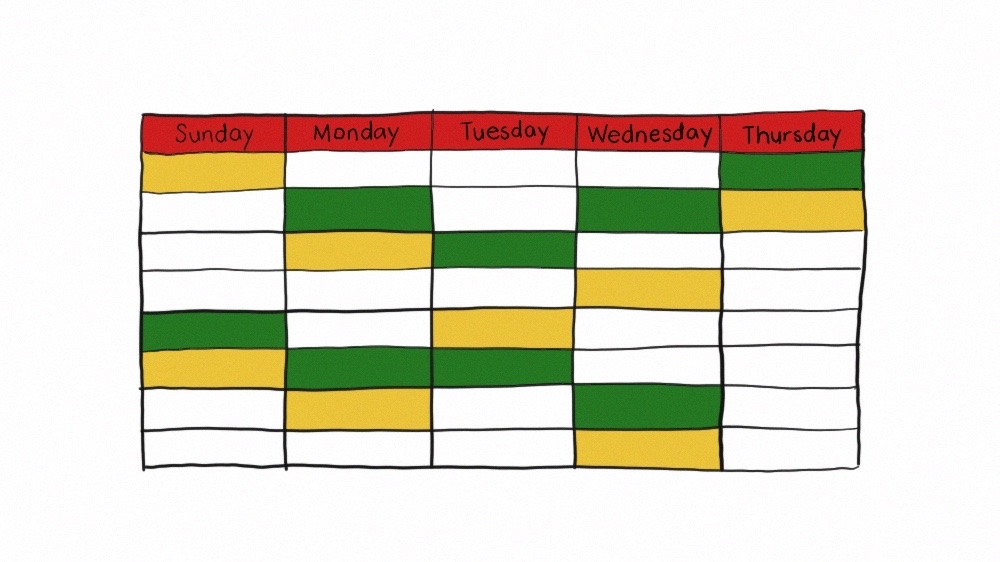

For Jen Simon, a writer and mother in New York City, the trigger that reminded her of her journey with postpartum depression and anxiety was an Excel spreadsheet.

When her first son was born in 2009, her husband designed a colour-coded spreadsheet for her to fill out during her days at home with the baby. “Green was for sleeping, yellow was for eating, and so on,” Simon recalled.

Simon’s husband is a lawyer, accustomed to billing in crisp six-minute increments and keeping immaculate records of his time. It felt natural to him to track the minutiae of their new son’s days. But their son had not got the memo. “We didn’t know that newborns didn’t have schedules,” she said.

Simon’s postpartum anxiety flared up a few months after she gave birth, when her son began waking up at 4am every day. Since he already woke frequently in the night, the crack of dawn rising proved to be the tipping point for Simon. “My anxiety was so different from anything I’d ever experienced before. It was very physical – I describe it as being electrified,” she said.

“As soon as we heard school was cancelled [because of the pandemic], my husband wanted to make a schedule for the boys,” Simon said. Instantly, she was reminded of the spreadsheet he had designed when their son was a newborn. “The hair on the back of my neck went up,” she said. Her husband backed off quickly when she explained how much the idea of a schedule reminded her of the overwhelming first months of motherhood.

Laura Huddy, a banker, mother of two and founder of the Maternal Health Alliance of Maine, noticed the physical warning signs of anxiety as the COVID-19 virus crept closer to home. “When I first came home from the hospital with my daughter, I just felt funny – it was this tingly, prickly feeling on the back of my neck. I noticed that pretty early on [in the pandemic].”

Huddy’s anxiety is accompanied by insomnia, just as it was when she became a mother 11 years ago. As a commercial banker, she is currently working extra hours to assist small business owners affected by the pandemic, while also homeschooling her two children. “I’m incredibly exhausted, but still not able to shut my brain off,” she said.

A feeling of powerlessness over our collective, global situation also echoes Huddy’s postpartum struggles. “There’s this desperate feeling of wanting to go back to how things used to be, and knowing we can’t,” she explained. “It smacks me in the chest.”

Regina Booth, also a banker and mother of two, agrees. Since the pandemic began, she has noticed a resurgence of the waves of doubt about herself as a mother that echo her postpartum anxiety. For Booth, the panic first hit when her husband was returning to work after her first son, now aged five, was born. “I remember wondering, how do I get out of this? How do I return this baby?” she said. With time and support from her family, Booth’s anxiety ebbed, and the worst of it subsided by the time her son was about eight weeks old.

Attempting to balance work and parenting amid a lockdown has brought those feelings rushing back.

“I learned early on that I wouldn’t be a very good stay-at-home mom,” Booth said. “Now, all of a sudden, I’m forced into this role that I didn’t choose and would not have chosen for myself.” For many, the uncertainty of how long the pandemic will last adds to the distress. “If someone told me it would be two weeks or a month, I’d suck it up. But that feeling of ‘Is it going to be like this forever?’ That’s a very overwhelming feeling.”

The path out

The path out of postpartum depression is often murky. I can not tell you exactly how long I suffered from it, or the day I knew for sure that it was over. There was no magic potion to tame my hormones and lift the fog and panic, no crisp homecoming to the version of myself that existed prior to experiencing it, because that woman had not been a mother.

My son is 11 now. Eleven! He plays video games. The first stirrings of facial hair flicker above his upper lip. He is sensitive and determined and witty. Still restless, still stunning. My love for him is a scarf that is constantly being woven, revealing unexpected hues and stitches, endless in length and depth. I can still feel the tangled knots of our early days together when I reach deep, the scar tissue where we are both tender and strong.

The road of recovery from a global pandemic, too, is blurry. We can not yet tally the scope of the damage, or discern which slivers of our old lives can be reclaimed and which, like casual handshakes, might be forever banished.

The only thing we know for sure is that what we are experiencing now will shift.

When I asked Simon if her journey with postpartum depression and anxiety taught her any lessons that are transferable to the current pandemic, she said, “Even if I can’t see it yet, I know something different will happen.”

Simon shared that acceptance is another tool she practises. “It took a really long time for me to realise I couldn’t change when my son was waking up. All I could change was my reaction to it.”

Booth is taking the advice she received from a friend during the peak of her postpartum anxiety. “Instead of asking how am I going to get through another month of this, I just focus on what I’m going to do to get through today,” said Booth. “Or even the next hour, if a day is too much.”

Therapy and medication became Laura Huddy’s primary armour against postpartum depression and anxiety. Now, these tools help her deal with her anxiety about the pandemic. “People go through crises and don’t know what’s happening to them. Now I have tools to deal with it. Now there’s a road map,” she said.

Huddy noted that naming her feelings rather than being swept up in them helps, too, as does sharing her feelings with those she trusts. “Being open about how you’re feeling and naming it can be disarming – and you’re going to find that almost everyone is experiencing similar feelings.”

Kleiman recommends mindfulness techniques for those struggling with difficult emotions which are triggered by past trauma. “What are you feeling, smelling, hearing, and tasting? Can you feel sunshine on your skin?”

She also recommends strong doses of self-compassion. The emotional load mothers are carrying during the pandemic is impossibly heavy, and yet many of us expect ourselves to shoulder it with grace and ease.

“At this moment of crisis, the best thing for women to do is give themselves permission to let go of whatever burden they place on themselves to be perfect. Perfectionism is just another way of being anxious,” said Kleiman.

“Getting through the day is enough. If you’re safe, if you’re resting and feeding yourself and your children, that’s all you need to do.”