The children colonial Belgium stole from African mothers

Taken from their mothers in what is today the Democratic Republic of the Congo, Rwanda and Burundi, decades on a group of mixed-race elderly people are fighting the Belgian state for recognition and reparations.

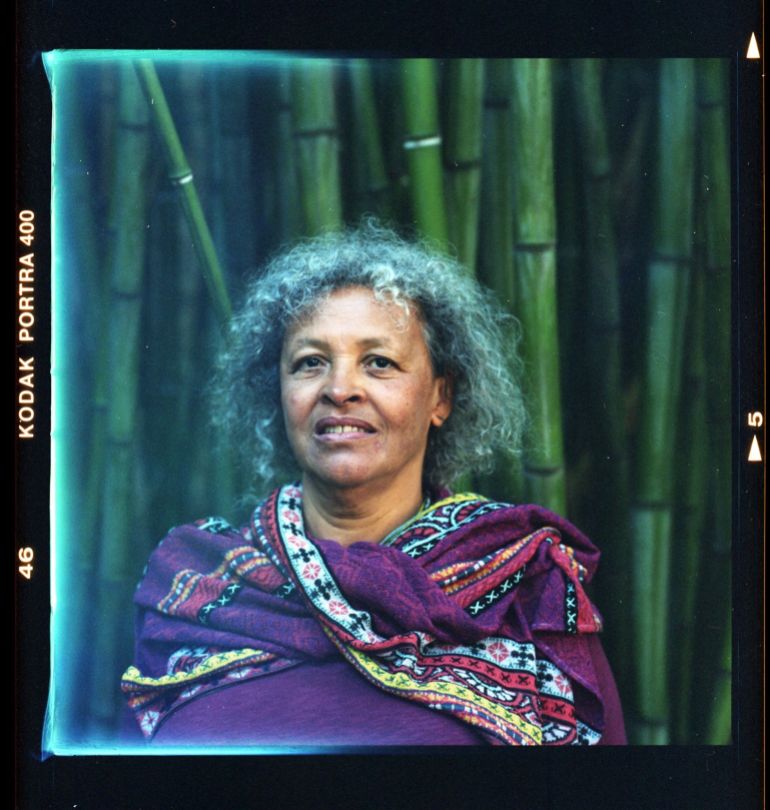

Monique Bitu Bingi, 71, has never forgotten how it happened.

It was 1953 when the white colonials came for her in Babadi, a village in the Kasai region of what is today the Democratic Republic of the Congo (DRC), then a Belgian colony. She was four, the child of a Black Congolese woman and a white Belgian colonial agent. Because she was mixed-race, she would be forced to leave her family and live at a Catholic mission. If she stayed, there would be repercussions: the men – farmers, hunters and protectors of the village – would be forcibly recruited into military duty and taken away. When the time came to leave, her mother was not there to say goodbye. She had left, unable to watch her daughter go.

Keep reading

list of 4 itemsMartin Luther King, Jr was radical: We must reclaim that legacy

From lynchings to the Capitol: Racism and the violence of revelry

Why does the US mythologise its former presidents?

Monique remembers travelling with her uncle, aunt and grandmother who carried her. She could tell something was wrong from her grandmother’s sadness. They walked west for about two days, crossed a river and slept in cabins used for drying cotton. When they reached Dimbelenge they hitched a ride northwest on a truck carrying the body of a woman who had died in childbirth. It was headed for Katende, in today’s Kasai Central province, where the St Vincent de Paul sisters’ mission was. Monique fell asleep. It must have been a Wednesday because weddings happened on Wednesdays and when she awoke outside the mission she saw a young Congolese couple, the bride dressed in white, and strangers everywhere. But her own family was gone. She remembers walking through the crowd, crying, until an older girl from the mission brought her inside to the others.

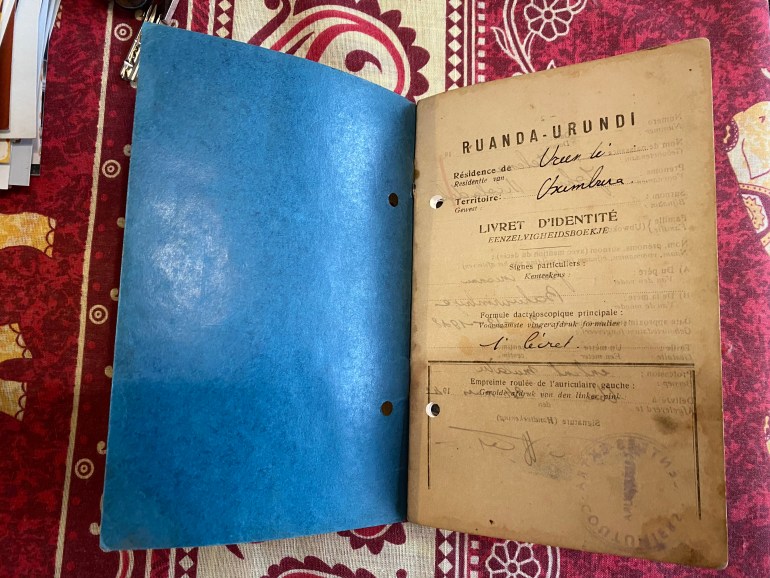

Among the countless abuses committed by the Belgian state during its colonial occupation of the Congo from 1908 to 1960, taking over from the exploitative and violent rule of King Leopold II which killed millions of Congolese, and its control from 1922 to 1962 under a League of Nations mandate in Ruanda-Urundi (today Rwanda and Burundi), is the little-known systematic abduction of biracial children from their maternal families.

This abduction policy has brought lifelong pain and consequences for the Métis – as they are known in French – who have tried to piece together stolen identities and histories. “It’s a catastrophe,” says Evariste Nikolakis, 74, who is Métis.

“When this kind of love is taken away from children, they’re going to carry that scar for the rest of their life,” Monique says. “It’s something that cannot be healed like other scars.”

In March 2018, an 11-point resolution (PDF) was unanimously adopted by Belgium’s federal parliament that recognised this segregation policy and took a big step towards measures enabling Métis to access their personal files, resolve issues faced by many who do not have a birth certificate and facilitate family reunions. In April 2019, then-Prime Minister Charles Michel apologised to mixed-race people for their targeted segregation, abduction and suffering. The Catholic Church in Belgium has also apologised. But there has been little progress since. Nothing has changed, say Métis.

Some Métis have fought for years for recognition and redress.

Monique along with four women born between 1945 and 1950, who lived together in the mission, say their racially motivated kidnappings constitute a crime against humanity. In June 2020, just before the 60th anniversary of the DRC’s independence, the women – all grandmothers – launched a historic lawsuit against the Belgian state seeking reparations and a reparation law for other survivors.

In a country that has yet to confront its brutal colonial history, biracial children stolen from their African mothers more than half-a-century ago want Belgium to answer for its past, a campaign of systemic racism and abduction and to address the deep wounds it inflicted. For them, it is a fight not just about the past, but also one to build an equal future.

Abandoned by the nuns

Monique speaks in French over a WhatsApp video call from Hasselt, a town in Flanders, Belgium’s Flemish-speaking northern region. She is with her youngest daughter and namesake, whose parrot sings loudly in the background while we speak. The older Monique wears thin-framed rectangular glasses, a black hoodie and her fingernails are painted a dark blue. She wears a solemn expression, but on occasion, she cracks a gentle, beautiful smile.

At the Catholic mission, the girls heard daily that they were the “children of sin”. They were told the devil created the Métis, and were baptised separately from the other Congolese children when no one was around to see.

The older children took care of the younger girls. They fed and looked after the babies, and attended school. They gathered the leaves of sweet potatoes to eat. In the room where Monique slept, at the head of her bed was a wall and on the other side, a morgue. She heard the mourners every night. She lived with Léa Tavares Mujinga, Noëlle Verbeeken, Simone Ngalula and Marie-José Loshi – the other women behind the lawsuit.

Were they always friends? “No – almost sisters,” she says. “One encourages the other.”

In 1960 the DRC became independent. Fearing violence from political turmoil in the wake of independence, the nuns prepared the children to leave for Belgium. But a priest prevented the girls’ departure. The nuns left, then returned, until one night when United Nations trucks took them away for good, abandoning the children.

It was 1961. Monique was 11. There were some 60 children including about 10 Métis, orphans and babies left on their own. Some of the babies died. When violence broke out in Kasai between different ethnic groups after independence, Bakwa Luntu militiamen arrived at the mission saying they would protect the children. Instead, they raped them.

“Every night for several nights they’d put the girls on the ground with their legs open and they would take long candles and put them inside their vagina,” says the younger Monique (who goes by her father’s surname Fernandes), 36, of what her mother and the others endured.

About a week later, a local administrator found families to house the girls. The violence around them continued. Bakwa Luntu fighters would brandish hands cut from their enemies. Food was scarce; they ate worms and grasshoppers.

“We are traumatised,” says the older Monique. She still has nightmares about that time and when she hears trucks at night, she thinks the fighters have returned.

It’s a whole adolescence taken away, she says. She had no option but to go on. “I had to be strong.”

“They were destroyed mentally and physically,” says her daughter.

About a year later, in 1962, a Dutch and a Congolese priest took the girls, scarred and skinny, back to the mission. Monique stayed there until she was 17 when she married a Congolese-Portuguese businessman, with whom she had seven children. She saw her mother every two years but they could never regain what had been lost. It is just “because we were born with a different skin colour” that mothers did not have the right to keep their children, Monique says.

In 1981, at 32, she immigrated to Belgium with her family for her children’s education. Now, with grown-up children and grandchildren, she feels it is time to speak the truth about colonialism through her experience, to address the lies in school books that paint it as something altruistic, Monique Fernandes says. Her mother and her “aunties”, as she calls them, believe their story should not be hidden.

“It’s important that the Belgian government recognises what has happened, and that they repair what they have done. A crime has been committed and they need to fix it,” the older Monique says.

Stolen children

Mixed-race children threatened a colonial regime that considered white Europeans to be racially superior.

“They were feared because their mere existence was shaking the very foundations of this racial theory that was at the core of the colonial project,” says Delphine Lauwers, an archivist and historian at the State Archives of Belgium who is researching, as part of the 2018 resolution, the targeted segregation of biracial children born during Belgium’s colonial regime.

Métis were seen as an aberration but also as a possible danger – as a future force for revolution if they stayed with their African families.

“It was always a question: will they be loyal or not?” says Jacqui Goegebeur – who is Métis – president of the grassroots movement Association Métis de Belgique/Metis van België (AMB), and a pioneer in the struggle for recognition of the history and consequences of the state’s discrimination against mixed-race children.

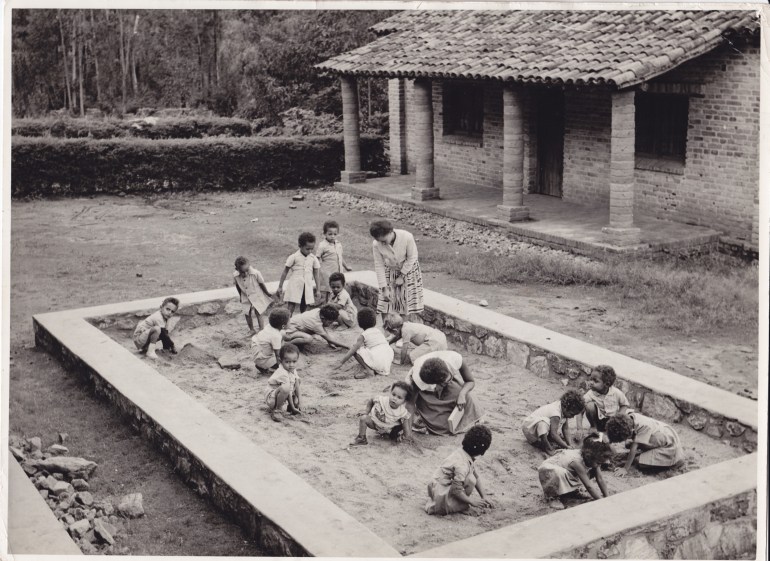

In 1952, a state decree concerning the guardianship of “orphaned” or “abandoned” children – in reality, those living with their African mothers or not recognised by their European fathers – led to the systematic abduction, segregation and isolation of mixed-race children who were locked away in religious institutions. Religious and state authorities were complicit.

Children born to women as a result of rape, situations where African housekeepers were treated as concubines, but also children from interracial local marriages unrecognised by Belgium, were abducted from their mothers by force or through coercion.

Segregation was couched as being in the interest of the child and their education. Correspondence from the time shows mothers were portrayed as unable to care for their children. Many mothers were told their children would return after their studies. The children instead became legal and administrative wards of the Belgian state.

Women who dared to fight back were painted as lunatics, according to Lauwers. Severine Uwerijinfura was 15 when she tried to leave a man 50 years older, whom she was sold to, with their daughter. He hunted her down with the police who threw her in jail. When she was released 30 days later, her child had been spirited away to Belgium. “We, the mothers, were scorned and psychologically killed,” she told Belgian newspaper De Standaard in 2010.

“Whatever the individual story, it has always remained in an institutionalised sexist and racist system,” says Chiara Candaele, a historian who works with Lauwers.

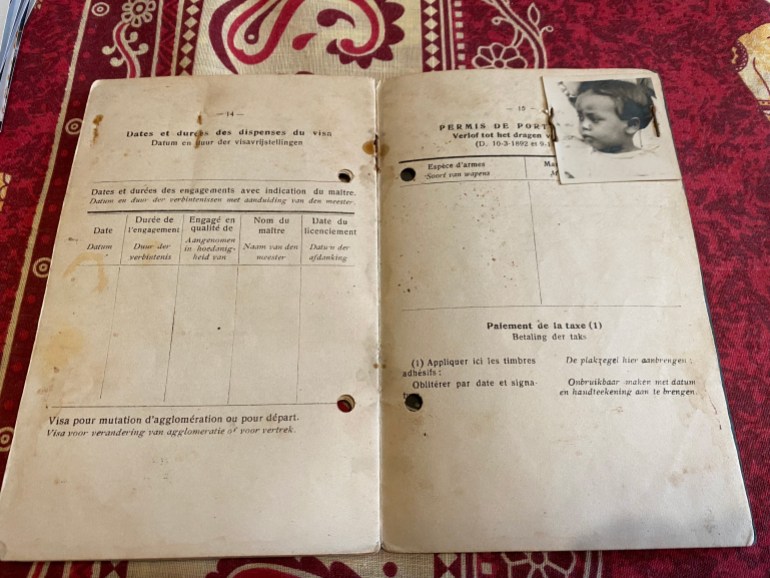

In such a system, white fathers – Belgian, but also Greek, Portuguese, French and Italian men – would recognise some offspring and not others. From the 1920s, fathers started bringing their children to Belgium on a private basis. In the lead-up to the countries’ independence, sometimes on daily flights, the state brought hundreds of children to Belgium, while many more were left behind. At least 283 children from the Kivu region in the DRC, and neighbouring Rwanda and Burundi were brought to Belgium. Many came from an institution in Rwanda called Save, presently the most documented and researched. There are more than 1,000 files in Belgium from that period for children sent to foster families and orphanages.

Lauwers says one of the study’s aims is to establish numbers, which vary widely. At the time of independence, there are indications based on existing sources that there were between 5,000 to 10,000 Métis across the territories, she says.

Children’s names and birth dates were changed, partly to protect the father’s identity and reputation – many came from elite families – and to make it hard to locate biological parents. But this also justified dislocation.

There was a belief in cutting these children off from their origins, says Lauwers. “It was a real theft of identity.”

“There was a system in place where they said, ‘Well, these children, they have ties to nobody, they are completely alienated. They don’t even carry the name of their fathers any more … We have to save them,’” she says.

Children were displaced to Belgium because some Belgian authorities feared they could be victims of ethnic violence, she says. Yet by separating children from their families and isolating them as a distinct group, they were put at risk by the Belgians. “They shouldn’t have [needed saving] from anything if the Belgian colonial regime did not place them in institutions, cut them from their origins.”

‘We need to know our history’

For the longest time, the history of Métis was hidden – even to Metis. Many have struggled to understand who they are and what happened to them.

In 2010, in response to white people in Belgium commemorating DRC’s decolonisation where – apart from the artists and musicians – people of colour were absent, Jacqui sought out other Métis so they could have a voice. She started the community Mixed2010, which later became Mixed2020.

She was astonished by the Métis’ stories that she heard. Many thought their mothers had abandoned them, and blamed them for their pain, but not their fathers whom they idolised. Paternal recognition created a hierarchy. This was destructive thinking, she thought. She had once believed her mother had abandoned her as Jacqui’s sister remembers their mother being like “ice” when they were taken. But better understanding her own story has helped Jacqui see otherwise.

“I decided we need to know our history,” she says.

“We have to stop the pain with our generation. We have to confront our history.”

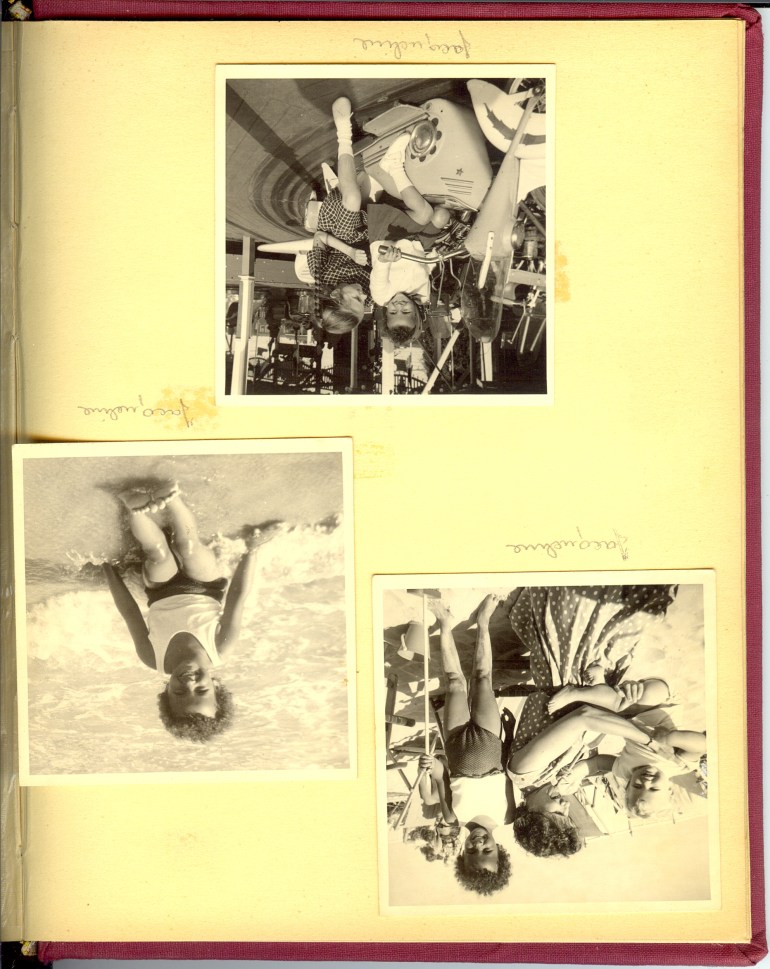

Jacqui was born in Kigali, Rwanda’s capital in 1956, when the country was under Belgian rule. Her mother was Rwandan and her Belgian father, who built houses, recognised his three children. Jacqui has his surname.

But her parents’ marriage under Rwandan law was not recognised by Belgium. When Jacqui was six months old and her sister two-and-a-half, their father died. On the day of his funeral, their six-year-old brother was taken to live with Danish missionaries.

Jacqui’s mother tried several times to rescue her son. The priests set dogs on her, Jacqui’s brother recounted in person many years later. Then he was taken to Burundi where his mother lost him forever. Two years later, the police came for Jacqui and her sister.

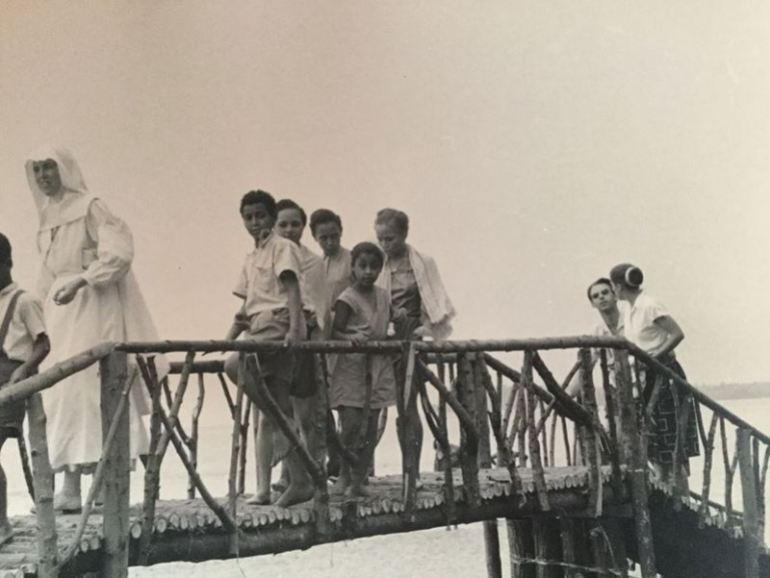

Mothers did everything to hold onto their children and show that they were looked after. Jacqui shows me a black and white picture over a video call of one mother with three girls in white European outfits and socks in Rwanda. That earth is red, she says. To keep those outfits pristine, they had to be laundered daily.

The girls were taken to Save. There she remembers sharing a bed – the blankets dark blue with red squares – with her sister, their heads on either side of the bed, their feet touching. As teenagers, when they next shared a bed again, they touched feet automatically. “It was very strange,” she says laughing.

At Save, Jacqui never smiled, behaviour the nuns informed her Belgian foster family about in a letter.

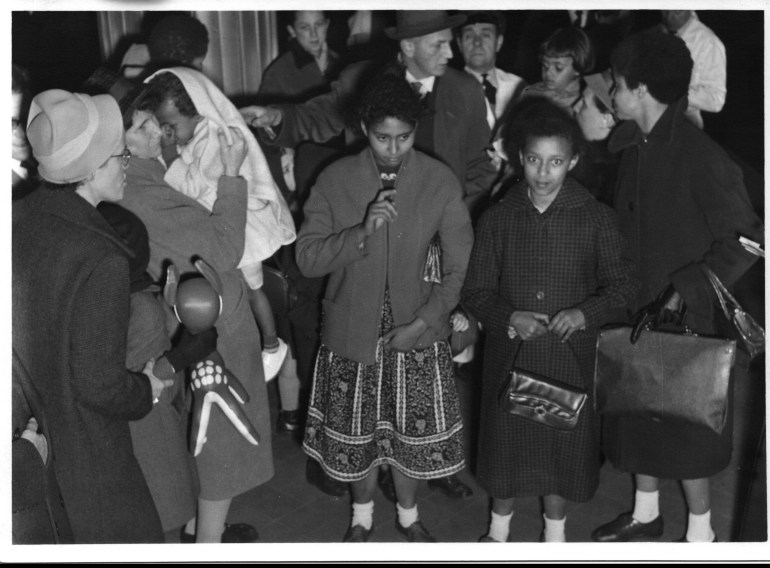

Jacqui was three when she arrived in Belgium. The plane landed on the coast because of fog, then the children came inland to Brussels by train. There are photos and footage of foster families clutching Métis children, and Jacqui sobbing in the arms of her foster mother who has brought a large spotted soft deer toy. As per policy, she was separated from her sister who was sent to a city 200km away from Blankenberge where Jacqui grew up.

Jacqui quickly became attached to her foster father. Her foster mother, a devout Catholic, carried the trauma of losing six siblings and her mother when their house was bombed during World War II. She adored little children but once Jacqui turned six “she wasn’t interested in me anymore”. From that age, Jacqui learned how to prepare her food in the morning.

She was never able to feel comfortable in the family and was treated unequally to her foster sister, six years older than her, who was free to bike around Europe in the summer, got new clothes and could use tampons. Jacqui instead had to babysit, wore hand-me-downs and had to use old blankets as pads.

For years, she forgot she had siblings until her sister wrote to her.

At 18, she broke away from the family. She wanted to study medicine, but they would not help her financially even though they received government money for her studies. Her foster mother blamed her for whatever went wrong; for her husband’s drinking.

At one point she decided: “I have to survive.”

‘Child of Belgian colonisation’

When Jacqui was 21, she returned to Rwanda for the first time and met her mother. She had received an inheritance from her biological father and was able to buy a small property in Ghent, the Belgian city where she lives today, and visit Rwanda. Before she left, her sister received a letter from the Rwandan embassy saying: “Your mother is waiting for you. You are old enough to come back.” Their mother, like others, thought they had left for their studies.

The meeting did not go well. People had planted seeds of doubt in Jacqui’s mind, warning her that the woman may not be her real mother, so she was wary from the start. When they met, they could not communicate in the same language and a crowd of onlookers had gathered to watch them, which increased the strain. Jacqui was overwhelmed. “I didn’t know if she was my mother. I didn’t want to care any more,” she says. She wishes she had been more organised and better prepared, to just be with her. “To see and to feel and to smell everything that was not in my life.”

After 1994, there was no possibility to repair that, she says. About 10 years ago, she visited again with her sister and met, for the first time, their younger brother, born when their mother remarried. Through him, she learned that her mother, her daughter, and sisters were all killed in the Rwandan genocide. She now financially supports her brother and his sons.

“I’m a child of Belgian colonisation,” Jacqui says, adding that everything that has happened comes from the oppression and racism that robbed her of the chance to be her mother’s child.

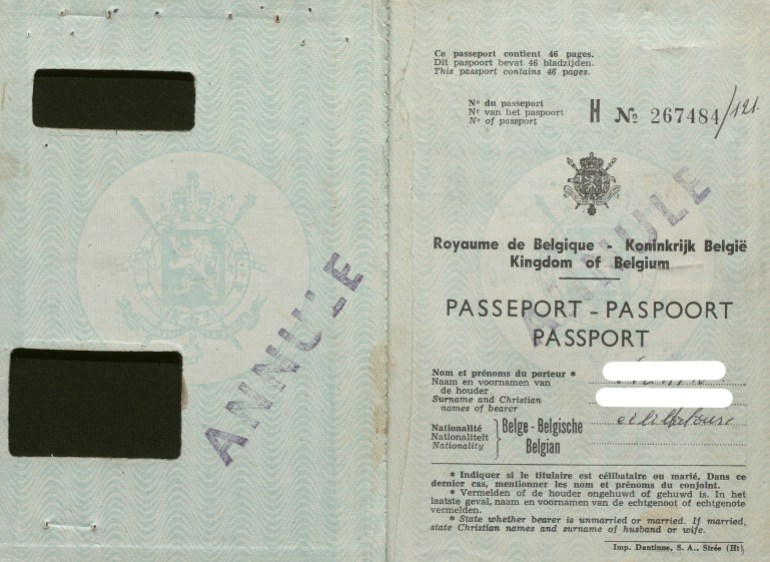

But she also counts herself lucky. She has information about her family and a birth certificate, she believes, because her father officially recognised her and because her foster father meticulously collated a dossier of her documents. She found her birth certificate at 11 while playing one day in his office. The Dutch word “bastaard” is on it; it was “proof” of what the authorities back then considered to be a “sin”, she says.

From her sister’s personal files retrieved from archives in 2014, they learned that their mother fought hard to keep her children. She hid her daughters from the police and on the third attempt, force was used to take them. This confirmation gave Jacqui peace. “It is the only thing I wanted” to know, she says.

But she always sort of knew. She shows me a thin silver chain over a video call. She lost the original. This is a replacement that she bought of the one her mother gave her when she was a child. She says she would not have had this jewellery if she was abandoned.

Since 2014, through AMB, she and others have taken the fight for recognition, awareness and to address issues faced by Métis to parliament and politicians.

Retired a year ago from a decades-long career in IT with IBM, Jacqui continues to lobby for the Métis. She will also use her expertise in software to aid an upcoming Flemish-government backed centre that will help people trace their biological roots. Through Mixed2020, she has found many people grappling with the question: “Who am I?”

“I had the luck that I know how important it is – to have a name, to have an explanation. I know it and I don’t want anybody to miss that.”

‘Unknown’ fathers

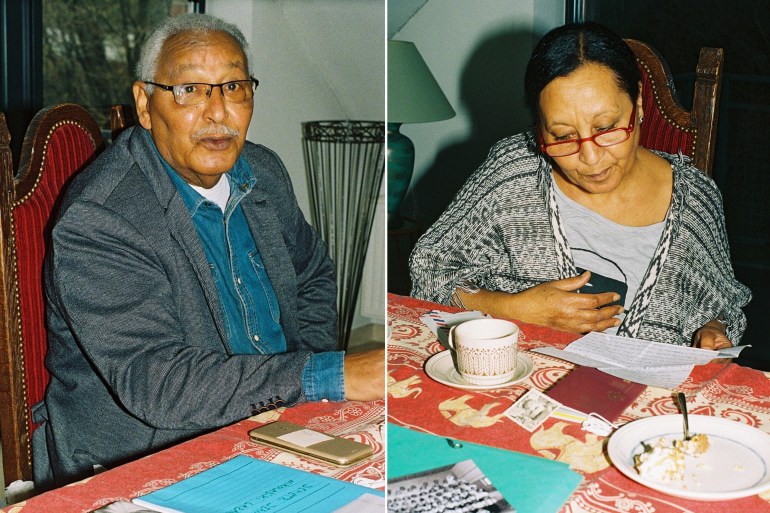

Evariste Nikolakis, 74, sits at his sister’s dining table, in the municipality of Ottignies in Belgium’s French-speaking region of Wallonia, the bare branches of winter trees visible through the glass sliding doors behind him. A neat stack of black and white photos and green folders containing documents from his and his sister’s childhood sit on the table. His sister Léna Nikoladiki, 72, a petite woman with high cheekbones and hair pulled into a low twist, moves around taking papers of note out of their folder.

Despite being separated by the Belgian state, the siblings are close. “She is all I have,” says Evariste, who lobbies with Jacqui through AMB.

Evariste was born in Usumbura, today, Bujumbura, the capital of Burundi.

Expressive, frank and with a deep voice, Evariste says he has fragments of memories of his biological father, a Greek agronomist who was well-known in Bujumbura. He remembers his father holding his hand or arriving with a huge travel trunk. His mother was barely a teenager when she had Evariste’s oldest brother.

Mostly he remembers a loving home environment with his mother, Olive Bahuwimbuye, and his three siblings. When he was about five years old, his mother was forced to give up her four children in just one day – him, his younger sister and two older brothers, all about two years apart in age.

The brothers went to the DRC, while Evariste and his younger sister Léna travelled by dirt road to Save. There, boys and girls were divided. They would see each other during recess or in the evening while collecting water. They both remember crying a lot in those days because they desperately missed their family.

The atmosphere was very strict, says Evariste, and the nuns would punish children for accidents like wetting the bed.

Evariste says that he, and other abducted Métis, have the same issue: “We run behind our own identity all the time. Our identity doesn’t exist.”

He says when the colonial administration came to abduct children they had information about who the parents were. But they cannot easily access this information today.

Evariste points out the irony of supposedly being the children of an “unknown father”, as stated in his and Léna’s documents.

“These men were the ‘vedettes’ [the stars and celebrities] in all the hills of Africa,” he says. “So they were well known by everybody over there. They were anything but ‘unknown fathers’.”

Like many Métis, neither sibling has a legitimate birth certificate. This has posed administrative problems throughout life when it comes to getting married, buying property or inheriting, as well as the burden of trying to prove one’s identity over and over again. Even Métis recognised by their fathers have had to be formally adopted in later life to receive their inheritance.

In 1960, Evariste, then 14, was displaced to Belgium. At 18, he tried to return to Burundi, but could not get a passport with a birth certificate. He later needed to obtain a legal waiver to be wed. Now, married for 48 years and father to a son, he worries what will happen when he dies.

Evariste has requested his birth certificate from the known channels, but he does not think it exists. “To an extent, I don’t even exist today,” he says.

The nuns at Save changed his name from Nicolas to Evariste. He says names were changed to “scramble our origins”. If children had an inkling of their father’s surname, they could have a phonetic version, so he got one in Belgium that he vaguely remembered – Nikolakis.

In one document predating his displacement to Belgium, the surname Nikolakis appears. He says the date was either changed or authorities knew his surname but insisted on writing “unknown father”.

Names and dates botched and manufactured are only part of the falsehoods that documents from agencies handling the siblings reveal.

Léna, who three years ago obtained some of her files through the Flemish government child and family services agency (anyone adopted or placed in Belgium from the age of 12 has the right to access their adoption file) shows a document saying that her biological mother was unable to care for her child, that new local customs meant her community rejected mixed-race children and that she was abandoned.

Another document concerning Evariste states their mother agreed to him going to study in Belgium. Her name is wrong; her signature is absent. There are two “witnesses”.

The Association pour la Protection/Promotion des Mûlatres (an offensive colonial term that likens mixed-race people to animals), or APPM, was one of the key organisations that financed the children’s displacement to Belgium and managed their living situations. In the files, a letter sent from APPM to a priest in Burundi carries news to be relayed to their mother but to be kept confidential; a sleight of hand, Evariste believes, so she would not talk or go looking for her children. It falsely states that Léna asked to become a naturalised Belgian.

Reading the documents, Evariste gets fed up with the lies and contradictions. “Two pages in, I’m sick of it,” he says.

Time is running out

When Evariste arrived in Belgium he was sent to an orphanage called Bambino, while Léna went to live with the family of a dentist. Their brothers were left behind. The dentist brought Evariste home for the summer, but after that the APPM sent him to various boarding schools, and to the home of a retired policeman whose house he fled after he tried to sexually abuse him. He then ended up in a shelter run by a kind priest in the city of Namur where there were Métis, Hungarian refugees and former convicts.

Evariste knows the stories of many Métis. There are beautiful stories, he says, but others “went through hell” – children who suffered slavery, rape and were denied education. But it is the mothers who never heard from their children again who suffered the most, he believes.

In 1997, he went with a Métis friend to trace his roots. In Bujumbura, he found his mother’s sister and learned his mother had died in 1984.

Through his aunt Fabiola, he reconnected with his big family and second-oldest brother, the only one still alive. She told him about his history and his mother’s suffering. “She became crazy. She started to drink a lot; she drank herself to death. And she was even sometimes looking after planes trying to see if they were bringing back her kids,” he says.

“I can die now because I’ve seen you,” he recalls Fabiola telling him. “I can go in peace.” She died two years later. He made a promise to her to look after her children and grandchildren including a foster child. “I kept that promise,” he says.

He now has a Burundian passport, with his mother’s surname.

“They wanted to make orphans out of us. But that’s not what they’ve achieved. They achieved to make us the biggest family there can be,” Evariste says defiantly, referring to the Métis and the family he found.

The search for identity continues. In mid-January, two weeks after we last spoke, Evariste says that his friend visited the Catholic church in Bujumbura where he was baptised. On his baptism card, his father is not listed as “unknown” but carries a baffling, generic name: “Europianus”. Curiously, both his baptism names are Evariste and Nicolas, although his mother only ever called him Nicolas and he remembers receiving the name Evariste at Save. He says to get the church to “give back” this identity paper, the institution requests payment of the tax accrued since his birth up to today.

Both he and Léna want the government to rectify the damage done.

He has one expectation – that the government puts into practice the resolution they voted for. “It’s just words in the air. If there is not a law to enact that resolution, it doesn’t mean anything.”

Time is running out, many Métis say.

“It makes you wonder if they are not actually waiting for us to die so they will then do something,” says Evariste.

For Léna, action is important so they can pass their history on to the younger generation. She wants people to know what happened. “It turned my life upside down,” Léna says.

Jacqui says she and others want goodwill and progress from the government to address issues including administrative difficulties to end the “harassment” of having to constantly prove one’s identity, or bringing family members from the DRC, Rwanda or Burundi to visit – like a mother or a sibling whose existence was discovered years after separation.

At least one mother in the DRC, reunited with her Métis daughter who tried unsuccessfully to bring her to Belgium so she could take care of her, has died since the resolution.

To solve administrative problems documents to prove identity likely exist.

“We know that all the data for our birth is kept in the Belgian archives somewhere,” says Jacqui.

“They [the government] have to make the files accessible.”

The need to declassify archives

Following the government resolution, work is under way to index archives and make them accessible. They will learn more about their parents, Jacqui says. There is hope critical documents will be found.

Lauwers and Candaele, the historians at the State Archives, a team of two working on the four-year study into the targeted segregation of Métis, feel the urgency.

“It’s not common for historians to be so useful. I mean, to be potentially so useful,” Lauwers says.

The two are gathering and identifying records to study individual and collective trajectories from public and private sources and putting them into a database. These sources include the “African Archives”, about 10km long, from the colonial period which were managed by the Ministry of Foreign Affairs and are now being transferred to the State Archives, children’s files from APPM, until recently kept at the Africa Museum, as well as private files from adoption agencies and religious institutions. There are also documents held by the Vatican. They have to identify information and make it traceable.

They are also helping individual Métis in Belgium and elsewhere access information to reconstruct family links and better understand their history, and they aim to coordinate with the upcoming Flemish parentage centre that will help people track their biological origins. They also hope to find sources that prove identities to circumvent administrative problems caused by the lack of a birth certificate.

But there is only so much the historians can do. One of the biggest hurdles is that current legislation lacks a provision for automatic declassification of classified documents. Lauwers and other researchers are pushing for automatic declassification after a certain period of time.

Although the African Archives were mostly produced by public institutions and are therefore technically available to researchers, some documents – namely those concerning the colonial security service – remain classified. Due to current legislation, declassification is something that the relevant institutions must opt for, including State Security, which has not. What that means is that even if there is a lone classified document in a public file the researchers cannot access it – or even the room where it is kept – without special security clearance, which takes time to obtain. In fact, since starting the project in September 2019, Lauwers is still waiting for full security clearance.

It slows down research, she says. Automatic declassification would let them do their jobs and have a frank discussion about the past.

“If you cannot access freely the public archives that document what the people who had the power did in the past, it’s simply a deficit of democracy.”

She says the government cannot demand a comprehensive study on a topic and not care about the practicality of it.

It must take action, she says, so that the resolution is not a vague commitment and the argument of waiting for the results of the investigation to find solutions cannot be used.

“I think now they really have to take action regarding declassification and the administrative problems that they have the means to solve.”

Marie Cherchari, a spokesperson at the Ministry of Foreign Affairs, which is among the federal and public authorities and institutions responsible for the implementation of the resolution, says a lot of work is continuing. “The government is committed to advance this issue,” she says. This commitment is illustrated by the resolution’s inclusion in the coalition agreement signed in late September 2020 by Belgium’s new government, according to Cherchari. The research project and family reunification come under this department, which has declassified their archives. Cherchari says relevant embassies and diplomatic missions have received instructions for how to assist Métis to identify their biological family.

Sharon Beavis, a spokesperson for the Federal Public Service (FPS) for Justice, which is responsible for civil status requests and is analysing the issue of birth certificates, says the department is committed to addressing the complex issues faced by Métis. They have set up a contact point for administrative issues. When it comes to birth certificates, she cites the challenge of the limited official documentation, saying that FPS Justice is analysing all possible sources to determine personal data. “At this point, it is difficult to estimate if and when all requested birth certificates can be created,” she says, adding that they are pursuing “durable and legally sound solutions”.

A reparation law

For Monique Bitu Bingi and the other four women taking on the Belgian state, their fight is also for others in a country that has dragged its feet on addressing its colonial history. It is unclear, for example, how a planned parliamentary truth and reconciliation commission on Belgian’s colonial past in the DRC will deal with reparations, something the women firmly ask in their lawsuit.

Michèle Hirsch, one of the lawyers representing the five women, calls her clients extraordinary. “They are all grandmothers who came into my office one day and said, ‘Well, what can we do?’”

It is the racially-motivated systematic removal of young children from their maternal family – against the family’s wishes and under duress – to be installed in religious institutions, that forms the crux of the lawsuit.

“This is for us what we call a crime against humanity and for which the Belgian state is responsible,” Hirsch says.

They also hold the state responsible for abandoning the girls, as their wards, in a conflict zone and for what they endured.

The women and their lawyers are calling for the Belgian state to say it has committed crimes against humanity. This also allows us to inscribe today’s racism in yesterday’s history, according to Hirsch. “The colonial policy of Belgium … has consequences on what we are living today at the cultural level, at the historical level, at the educational level, at the level of the differences that are still there.”

They also seek reparation, an amount of 50,000 euros (about $60,700) through the civil justice system. They have asked for the appointment of an expert to assess the amount of damage.

“How do you put a figure on a lifetime?” Hirsch asks. “Wasted or maybe not wasted, because that’s one of the things I really want to emphasise, the courage of our clients. They have built wonderful lives in spite of [everything].”

Last, they are asking for a reparation law applicable to everyone who has faced similar injustices. “It’s a matter for all of us. It concerns all of us. And therefore, it concerns our government and our parliament.”

Their fight could be historical, Hirsch says. And it is not just about the past.

“Through what these women do, our clients, they also transmit to their children, their grandchildren, a struggle. And a struggle for equality,” she says.

“They have an extraordinary courage, an extraordinary force of life. They can move a society.”

For Evariste, the lawsuit could help others to come forward. He also believes a law would help Métis. “To clarify, to state clearly, that Métis have been victims of segregation, abduction and to recognise their civil status,” he says.

Every Métis who has suffered deserves to be heard and recognised, Monique believes.

“A child’s life starts when it’s born and it’s held by its parents – when you’re safe and you have your whole future in front of you and that’s when it was cut down and taken away,” she says.

Hers is a fight for women and from women. “It’s women standing up to fight for their children and to fight for what is right for them,” Monique says. “Every woman has the right to keep her child and to love it.”

–

If you are looking to access your personal history linked to a mixed-race person born during Belgium’s colonial period, contact metis@arch.be or visit www.metis.arch.be