Diggers and dreamers: Vinyl collectors in Africa’s city of gold

In Johannesburg, South Africa, record obsessives find common ground in DJ booths, thrift stores and music fairs in their little town of vinyl.

It is about an hour’s brisk walk from Jeppe High School for Boys in the east of Johannesburg to the Kohinoor record store in the inner city.

More than 20 years ago, it was a trip Mxolisi Makhubo and his small group of hip-hop loving, self-proclaimed “outsiders” at their macho school made about once a month.

Keep reading

list of 4 itemsA Hard Road from Home: Music and Fashion

Ghana Controversial: Music from the Ground Up

How are African musicians challenging the ‘Afrobeats’ label?

“We used to take our bus fare and save it up for a month to buy records with and we’d walk to town, which is where we’d catch minibus taxis back [home] to Soweto,” the now 37-year-old architect told me on a summer’s Sunday morning over a cup of tea at his renovated house on top of a ridge not that far from his old school.

“We felt alienated, because we were in the chess club, we were in the poetry club, the choir, we were cultured … so music became a space for us to escape, but also to feel comfortable outside these hypermasculine attitudes within the school.”

That was 1998, four years after the end of apartheid, when the world of music was still slowly opening its doors to South Africa after a period of sanctions and cultural boycotts against the racist state had left the country isolated from much of the international cultural scene. Kohinoor, which opened in 1950, used to stock an eclectic range of records, but with a focus on jazz, both local and international. With its bold, bright yellow and black logo, it stood out among the drab shops on street level in the bustling but bland inner city.

“At first, we used to walk past Kohinoor – but just the aesthetics of the space and seeing people who were passionate about music caught our attention. They were much older than us, but we started going there,” Mxolisi says.

“Even before I understood why, I was buying records … I bought them just for aesthetic purposes, because I wanted to look like the guys in the videos.” As a politically and culturally aware teenager these videos by conscious rappers like Public Enemy and other political crews appealed to him.

“We started buying records, things we didn’t know. One of the earliest things from that era was getting a Doug E Fresh record because it was hip-hop, and it felt like I had finally arrived.

“So, it felt like my life was in sync with the videos I was watching, totally out of sync with what everybody else was doing at school. Because we were in sync with those videos, I think that’s where my love for vinyl started.”

Jun: Tokyo to Joburg

A decade before Mxolisi began rummaging through the records at Kohinoor’s, a world away in Japan, then-eight-year-old Jun Morikawa sat on a Tokyo metro train with his grandfather, and the latest Michael Jackson record on his lap.

It was 1987 and Bad was perhaps not the album the Miles Davis-loving, record-collecting jazz drummer wanted to get for his grandson, but the boy had asked nicely, and he could not say no to that.

Now 41 and living in Johannesburg, Jun, sitting under an old lemon tree in my garden, leans back with a gentle smile replaying the memory of how he unwrapped the record before he even made it home that day. The outing set off a happy habit that still continues unabated.

“I saved pocket money to feed the habit, or I asked my grandfather, ‘please buy this, buy that…’ My parents never understood my hobby, but my grandfather, because he’s a musician, he understands my needs.”

Jun reflects on the record that kicked off his collection. “I started looking at everything on Bad, but at that time I couldn’t read English. Luckily Japanese albums always have an obi-strip – it’s in Japanese, translated from English.”

An obi-strip is a paper spine card or a folded paper flap that usually contains an album’s release information in Japanese and is wrapped around the spine of Japanese albums. It stimulates their habit and helps record junkies with their “detective work” to explore more vinyl fixes.

“One of the reasons why I love vinyl, it has all that information on the sleeves – so I could read who was the drummer, who was the producer – ‘Oh, it’s Quincy Jones’… Because there was no internet, not much information, you used the album information, and you’d think ‘I need to buy more Quincy Jones albums’.

“The first time I listened to that album, Bad, it changed everything for me, because up until then I had just been listening to my grandfather’s jazz.

“I had seen Michael Jackson on Japanese TV. It was a shock, like being struck by thunder … but a nice shock! Then I got the record and it started my passion for music. It never stopped, it just became worse,” he says with a wide smile.

“At school I was the only one who listened to that type of music. They thought I was weird.”

A little town of vinyl

The city of gold, Johannesburg dates back to when the precious metal was first discovered here in 1886. Today, it is South Africa’s largest metropolis and one of Africa’s most populous, home to almost six million people and spread over 2,300 square kilometres of hilly land. But it is also a small town in some ways, especially when it comes to music.

In similar-sized cities around the world, there are enough people who collect vinyl records, especially the progressive ones to the left of the mainstream centre with adventurous tastes, to make for a thriving scene. But in Joburg, there are not that many of us. So like-minded folks find each other, even if not as friends, then at least by bumping into one another on dancefloors, in DJ booths, at record stores or in vinyl fairs in our little town of vinyl.

I’m a 59-year-old white Afrikaner, a veteran journalist, arrested several times by apartheid police and badly beaten up by them in the days before democracy, probably more for also being from the same ethnic group than for my clear opposition to their racist policies. But it was inevitable that my path would cross with these two fellow travellers who are also passionate record collectors, crate diggers and DJs: Mxolisi, born and raised in Soweto, who has been playing avant-garde music to his baby daughter Thando since her birth in early 2020; and Jun, the Tokyo native who works in logistics and shrugs his shoulders and smiles gently when kids call him “Jackie Chan” when they see him DJ’ing at reggae sessions in Joburg’s townships.

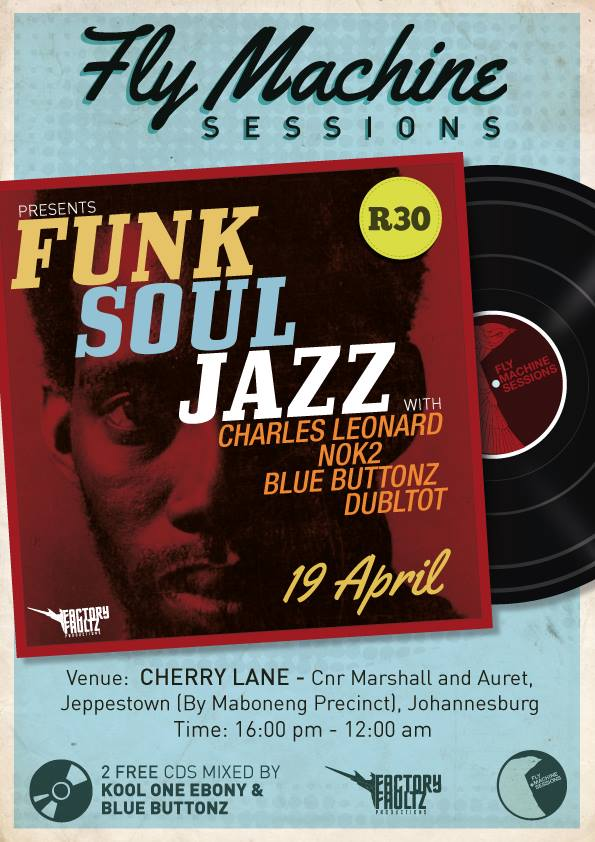

The first time I DJ’d with Mxolisi was at a strip club called Cherry Lane in an admittedly sleazy part of Joburg. It was a Saturday in April 2014 – I still have the flyer. A friend somehow managed to get the venue for free because the strippers were off duty that night. I brought my teenage children along, and during my set they made themselves comfortable on the small stage with its pole in the middle. I looked up from the DJ booth and noticed they had swiftly moved across to the opposite side of the room. “A cockroach ran across the stage and we thought it’s safer to stand far away,” my giggling daughter told me afterwards.

Mxolisi played after me. He did not hold back, and played some challenging, eclectic music. But he kept people out on the dancefloor throughout – because of his great selection of music and technical skills on the decks. We started chatting after his set and became friends straight away.

Jun remembers the first night we DJ’d together – January 16, 2016 at a session called Blame it on the Boogie at Kitchener’s Bar in Braamfontein, a hub for student nightlife in the city. I played the ‘70s soul song I Am the Black Gold of the Sun by Rotary Connection in my set.

I remember how Jun filled the floor with his exhilarating set that night, flawlessly mixing soul, reggae and hip-hop, sending the energy levels bouncing off the ceiling. Like with Mxolisi, Jun and I also became friends straight away.

Apartheid: the ideology of apartness

When I grew up in the 1970s, apartheid was everywhere.

The evil racist system was not only used to brutally oppress Black South Africans and forcefully segregate them into under-resourced townships, give them an inferior education and violently suppress any justified resistance. It was also used to indoctrinate young white Afrikaners like me, to make us believe we were a superior race, to narrow our minds and to suffocate any questioning.

They wanted you to only mix with your “own kind”, for people like me to listen to Afrikaans music, wear conservative clothes and keep their hair short, because “you don’t want to look like a Beatle, do you?”.

My way of resisting this came through music. I used my limited pocket money to buy records as a way to escape. I bought foreign music newspapers from which I could imagine kaleidoscopic lifestyles much more glamorous and exciting than mine. And as soon as I put the needle on my records, the dogmatic fog lifted. My imagination would take me partying with Mick Jagger and James Brown, flirting with Donna Summer and being serenaded by Joni Mitchell.

Every Monday morning at my secondary school in Vereeniging, a large industrial town about 80km south of Johannesburg, would start with assembly where one of the male teachers would read from the Bible and have a little sermon after it. One of them, hated for his voracious appetite for corporal punishment, was nicknamed “Goliath” after the biblical giant because of his massive size.

Normally assembly would be over quite quickly, except when it was the reactionary Goliath, who would zealously enforce the doctrine of apartheid in his homilies: “You must steer clear of jazz and abstract art,” he thundered in one session that I still remember to this day. “It is Communist and will lead you down a bad path straight to hell!”

To my rebellious 16-year-old self, back in 1978, it sounded like exactly the kind of road I wanted to explore. If Goliath said it was bad, it must be brilliant. I went to the surprisingly well-stocked town library that same week. I borrowed a book on the artist Pablo Picasso and a vinyl record, Kind of Blue, by jazz genius Miles Davis. Both blew my teenage mind.

Even though I had been collecting records since the age of seven, Miles set me on a path of wider exploration, both in terms of music and art.

But it was not always easy to find. In the decades before democracy the apartheid overlords tried their best to suppress free thought and racial mixing in every way possible, including when it came to the music we listened to.

The formal, government-appointed censorship body, the Directorate of Publications, even had the power to ban music. But this body only responded to complaints, and so it only made its banning decisions about material that had been submitted to it. The directorate formally banned fewer than 100 pieces of music in the 1980s.

However, the government used its control of the powerful state broadcaster, the South African Broadcasting Corporation (SABC), to prevent “undesirable” songs from being played. Artists were required to submit their music for scrutiny to an SABC body called the Central Record Acceptance Committee. Its members met weekly to review all music intended for airplay for evidence of anything that failed to comply with government policies.

They banned thousands of songs. These were songs that had political messages, encouraged racial mixing and liberal lifestyles. Even songs consisting of more than one South African language were banned by the fanatical censors – as they took the ideology of apartness to its extremes.

To ensure that these rejected songs did not make it on to the air, stickers indicating what to avoid were then placed on album covers – “offensive” songs were made illegible with pen scribbles. Vinyl records were physically scratched with a sharp object so that the needle would jump when playing an “offensive” track.

But in the early 1990s South Africa started experiencing a cultural spring. The SABC was allowing more “subversive” music to be played on the airwaves. In 1994 the country had its first democratic vote in which a Black president, Nelson Mandela, was elected. It started the transition to a saner society on many planes, including culturally and on grassroots levels.

Mxolisi: ‘It felt like we were in New York’

Mxolisi grew up in South Africa’s largest township, Soweto, about 27km from central Joburg. He is still friends with the guys from high school and even more of a passionate vinyl record collector, records he uses in his famously eclectic DJ sets.

By the time he was in high school in the late ’90s, the real world outside was changing. But because of the deep-rooted pervasiveness of apartheid the changes many Black South Africans were hoping for were slow to materialise. In fact, many remain elusive to this day.

One of the changes that did happen back then was access to better schooling for some: Mxolisi and his friends were among the first Black students to attend established formerly white-only schools in a predominantly white suburb.

With their eclectic, cross-cultural tastes they brought with them a certain nerdish cool to their previously white school as well as to the Black township.

Mxolisi smiles bashfully. “You still get people now saying ‘Oh, you guys were into that stuff ages ago and you turned me on to it’. But at the time it was totally uncool and we were made to feel like total outsiders … we were not listening to kwaito (Black South African house music) all the time – we also listened to it, but that was not all we listened to.

“And you had to belong to a certain ‘scene’ – you had to be a hip-hop guy, or a kwaito guy or a rock & roll guy. But we didn’t choose any scene – we could one minute be with the kwaito guys, next minute with the hip-hop guys and next with the rockers.”

He recalls the DJ and graffiti battles that happened there in the late-90s with a wonderfully dry, self-deprecating sense of humour, punctuated by a generous laugh. Mxolisi has the perfect, laidback chuckle for a vinyl DJ – it sounds like a deep bassline slowly being wound backwards and forwards on a turntable, ha-ha, ha-ha, and then gradually picking up speed, spinning into a lusty laugh.

“We’d be playing (jazz pianist) Duke Ellington and it was totally out of sync with what the other 16 year olds were doing. It was very pretentious, but at the same time it felt like we were in New York or any other part of the world, and not in the middle of Soweto.”

He took up DJ’ing and graffitiing. “DJ’ing and graffiti were perfect for my personality because you could be in the background and also you didn’t have to remember lyrics …” Mxolisi gives his sonorous laugh.

He still has a few of those records. “Definitely the hip-hop records … the other ones I had to replace because at the time you were battering records, because you were scratching, or attempting to scratch … The hip-hop ones I really looked after because I wasn’t playing hip-hop back then, so they survived.”

Jun: ‘I sleep among the records’

Still nurturing the seeds planted by his Miles Davis-loving grandfather when he was a boy, Jun has not stopped collecting records.

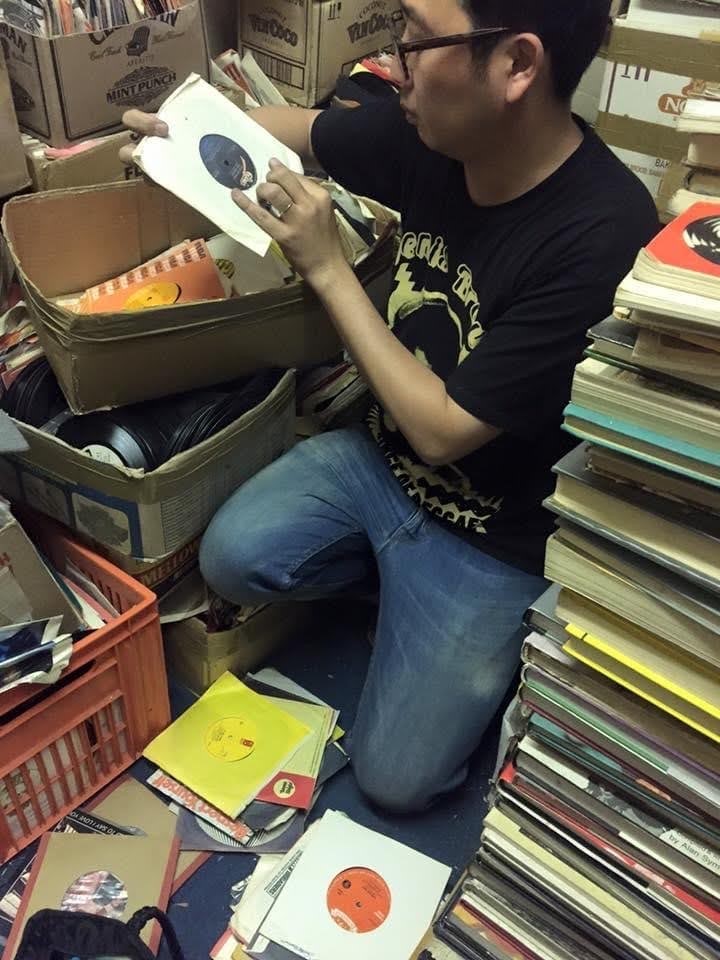

When he moved to Joburg six years ago, to head the Africa section of an international freight forwarding company, he was forced to leave his records at his parents’ home in Tokyo because it was impossible to bring them all the way to South Africa – they fill up an entire room.

“When I go to visit, I sleep among the records.” His eyes go dreamy as he transports himself to a different time.

How many? “I never counted but it’s around 15,000 records … I was counting until maybe 3,000.” And he has not stopped buying records since his arrival. “I’ve got about 5,000 here in Johannesburg,” he tells me.

Vinyl DJ’ing was a natural progression when he first started collecting as a kid.

“When I was about eight or nine, I recorded Michael Jackson’s songs from his LPs onto cassette – my favourite songs became a mixtape. Next, I decided to buy DJ equipment – turntables and a DJ mixer.”

His musical palette also expanded to hip-hop, and with it that exciting detective work of connecting the musical dots. “When I listen to hip-hop, say The Pharcyde’s Runnin’, that song sampled the jazz musician Stan Getz – I know that song from my grandfather!”

By his teens Jun was DJ’ing at parties in Tokyo. And then he saw the film, Wild Style, the cult classic about hip-hop, graffiti, break-dancing and rap in ‘80s New York.

It had great hip-hop, but through a central character, the Jamaican immigrant Kool Herc, it also introduced him to another passion, reggae and its sound system culture. Sound systems are Jamaican street parties where DJs (selektahs, they are called there) and MCs (or toasters – reggae’s version of rappers) play records through stacks of speakers and people dance until the early hours of the morning.

“I then needed to know more about Jamaica, where’s that, what’s a sound system?”

In 1999, when he was 20, he went to the Jamaican capital, Kingston, for the first time.

Did he get to go to a proper Jamaican sound system? “Yes! The Stone Dub and Kilimanjaro sound systems – it changed everything!”

Jun gets an almost religious light in his eyes and slowly exhales. “The sound systems were a shock to my system – they’re crazy! Whenever in some ghetto area the selektah plays a good tune, they shoot a gun into the air! A proper gun, nobody shoots a gun when they’re in the crowd in Tokyo …” Jun laughs. “I have never seen a gun in my life! I was very scared because that bullet has to come down!”

The next year Jun, in his fourth year of university, had finished everything except writing his thesis. “My professor, she was a crazy professor, and we often talked about music. My major was global culture, so I negotiated with her: Can I go to Kingston? I will send you a draft of my thesis every week.” She agreed and he spent the next six months in Kingston. “My professor was happy with my thesis – she gave me an A. I still keep in touch with her to this day.”

Did he buy records while in Jamaica? “Yes, of course!” He chuckles.

Because he was a university student with limited funds, Jun started a small business with friends back in Tokyo to be able to buy records. He went to the vinyl stores in Kingston and bought reggae records which he sent to Japan, where his friends sold them.

Because of his profligate record buying for his own collection, it was not a huge success. But it taught the cost of the freight, tax, import duty and regulations. Degreed and back in Japan Jun joined a freight forwarding company where he learned how to do it properly, not to mention funding his even more obsessive record buying.

“I was spending $1,500 every month on records. That was my first year after graduating from university, when I first got a salary. To be able to buy vinyl, I didn’t buy lunch!”

Mxolisi: The beauty in connections

For a teenage Mxolisi, growing up in Soweto, vinyl was more than just objects of recorded music.

“The key thing was having something of your own. For the first time you’ve got some kind of money that you can spend on your own things, to make choices on your own what you consume.

“So, you accumulate, say, a collection of about 30 records, and you’re sitting in your bedroom with your headphones on, and you think ‘yeah, I’m starting to build up my own world’. For the first time you’re creating your own world, the world you want around you.”

There was a thriving DJ culture in Soweto. The scene should have been proof of how successful apartheid was at keeping South Africans separate, all the way down to the music they listened to: Black South Africans with house music; white South Africans with rock. But it was wonderfully eclectic.

“It wasn’t always just house music,” says Mxolisi. “(British band) Tears for Fears for example were quite big – and people were playing interesting stuff, like heavy rock band Led Zeppelin. My first copies of Led Zep I found in Soweto.

“There was this weird thing going on … people were not supposed to have those records, but when you get into someone’s bedroom you discover they have Led Zeppelin and you think ‘how?’, because South Africa is supposed to be clear cut: ‘Blacks like this, white people like that’, but there was this other thing that was happening.

“Through records you also had access to this other nuance of South Africa that often doesn’t get talked about,” he says, appreciative of grey areas where people listened to what they loved regardless of genre, race or style.

The DJs’ eclectic tastes rubbed off on a young Mxolisi, who still buys anything and everything, from jazz to soul, classical to rock, reggae to punk and way beyond.

Why do you still buy records, I ask him, instead of the more convenient and accessible MP3s.

He thinks a little and I can hear some of the architect that he is, in his reply. “In a world of too many choices, it still feels nice to have the restrictions to be limited to your record collection. I love limits, I love restrictions, I think convenience and access are overrated.

“When you’re inconvenienced you start building very intimate relations with the things you own – each and every record, I know where I got it, how I got it. I don’t think there’s the same kind of intimacy with MP3s.

“Also, you can’t read the sleeves [with MP3s], there’s a certain kind of beauty in being able to see connections.”

To prove his point, Mxolisi takes me on a fascinating, but extended and weaving musical journey: starting with jazz musician Herbie Hancock, via South African jazz exiles in London, across the channel to Krautrock, a lateral jump to Detroit techno, joining with Pierre Henry’s musique concrete, and – sort of – ending with the Russian constructivist film scene.

He sits back with a smile and that pleasant big bassline of a laugh rumbles forth.

And you won’t stop buying records? “No, not any time soon,” he laughs. “There’s been times when I thought, ‘I’m slowing down’. I sold a quarter of my collection at the beginning of [last] year, but I realised that I’ve been quickly making that quarter back. I thought I was done, but I’m not. I don’t think I’ll ever be.”

Jun: Records across Africa

In Joburg Jun’s days are filled with many of the same things he started years ago: freight forwarding, record buying and DJ’ing.

As part of his job, he travels extensively. “I have already visited 35 out of 54 African countries, that’s 70 percent of them,” he says.

“And when you go there …?,” I don’t need to finish my question. “Always!” he says with a broad smile, “I always go digging and buying records.”

Has he found any great records? “There are vinyl shops of course, but sometimes the stock isn’t great. But I’ve learned in Kingston how to find the best places for vinyl. What I do is to always find a place where the taxi drivers gather, eating and drinking. I would ask, ‘I’m looking for vinyl records, where can I buy them?’

“If 10 taxi drivers are there, then at least one will know of a place! I still use that lesson when I go into the rest of Africa.”

In Dakar, Senegal last year, Jun used his method and his charm – a taxi driver took him to a little shop with some CDs and a few vinyl records.

“But the owner took me to a warehouse – it’s the best in Africa I’ve ever been to with an amazing collection. I got West African funk, lots of Fela Kuti too, I bought about 50 singles that were great.”

The international vinyl market has totally changed. The international online marketplace, Discogs, with its more than 13 million recordings (vinyl and CD) for sale, has made it very easy to access records, but has also pushed up prices.

In Joburg, there are five main record shops where most of us vinyl obsessives go digging. With the COVID-19 lockdowns in the city, parties have largely been cancelled. So many of us get our musical fix by continuing the chase to find our respective elusive records.

The elusive record

What is Jun still on the lookout for, what does he still need, I ask.

“Everything!” he affects a sweet voice and chuckles.

His current obsession is dubplates, which are exclusive tunes cut specifically for a reggae or dancehall sound system, based on a commercial tune but with specific new lyrics praising the system.

A dubplate is very important for a reggae selektah – it says something about their status. Jun got the dancehall artist, Pinchers, to do a dubplate of his hit Bandelero in which he sang about Jun. “I negotiated with him to make a dubplate for me – he ripped me off, but I’ve got it.”

How much? “He charged me $400!” I thought I was sort of obsessive, but Jun!

I ask him: Is it like an addiction? Jun looks away shyly, “Yes, I am a little bit crazy.”

What does his partner Yumi think? “She thinks I’m an idiot! She regards me as odd.”

Later, I ask Mxolisi which record he still looks out for.

“There’s plenty, but one that comes to mind is (South African Afro Jazz band) Malombo’s Music of the Spirits released on Third Ear in 1971. That was after guitarist Philip Tabane left the band and was replaced by Abe Cindi on flute. That record is ground-breaking, with Malombo at their peak. The recording standard is amazing, the music fabulous … a band that’s clicked together. That’s one that I’m really after.”

How difficult is it to find it? “There weren’t many pressed because it was a small label. Someone in Brazil who I’ve traded records with before, offered to sell me one during the COVID-19 lockdown. The price was about $650 … and it wasn’t logical during the lockdown to even try and make a plan and find that kind of money,” he says.

For me, one of my elusive records is by a mysterious South African soul-jazz township band called the Star Beams that apparently released just one record, Play Disco Specials, in the mid-1970s.

A few months ago, I took a couple of days’ leave from work to go exploring for hidden vinyl gems, including of course that one, in a few small towns within driving distance of Joburg.

This is how it went: Avoid potholes. Arrive in a dusty, rundown town. Put on a mask. Walk into a sad little pawn shop or dimly-lit general dealer.

“Do you have vinyl records?” I ask the slack-jawed shop assistant, explaining by drawing circles in the air with my hands. “You know, those round black things you play on record players?”

The person would look at me, either perplexed or with pity – not sorry that they don’t have any in stock, but sorry for the excitable weirdo asking for something as obsolete as vinyl records.

So naturally, I had no luck. Not even a dusty box from under the counter with junk masquerading as records. Nothing, except for looks of pity or mild irritation.

In my mind, what I would have liked to find, is some rare gem of ‘60s or ‘70s South African township jazz or jive or soul, maybe even that Star Beams record, preferably in mint condition. But alas.

When I get home, I see online that the UK label, Mr Bongo, has reissued Play Disco Specials. Before ordering it from abroad, I call around Joburg’s record stores, but nobody has it in stock yet.

One store does have an original though – going for an eye-watering R4,000 (about $240). I can’t spend money like that during these pandemic times, and I’d be too scared to DJ with a four grand record, in case it picked up scratches. So I turn it down.

“Don’t you want to come and have a look?” my friend at the record store asks. “Rather not,” I say. If I held it in my hands, I knew I’d never be able to put it back.

I order the reissue from the UK for R300 ($20). It’s a brilliant record. But I will still keep an eye out for the original whenever I go vinyl digging. After all, we’re not only diggers, we’re dreamers too.